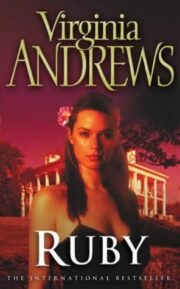

"I don't think most people would like that picture, Ruby," Grandmère told me one day as she stood behind me and watched me visualize another nightmare. "It's not the kind of picture that will make them feel good, the kind they're going to want to hang up in their living rooms and sitting rooms in New Orleans."

"It's how I feel, what I see right now, Grandmère. I can't help it," I told her.

She shook her head sadly and sighed before retreating to her oak rocker. I found she spent more and more time sitting and falling asleep in it. Even on cloudy days when it was a bit cooler outside, she no longer took her pleasure walks along the canals. She didn't care to go find wild flowers, nor would she visit her friends as much as she used to visit them. Invitations to lunch went unaccepted. She made her excuses, claimed she had to do this or that, but usually ended up falling asleep in a chair or on the sofa.

When she didn't know I was watching, I caught her taking deep breaths and pressing her palm against her bosom. Any exertion, washing clothes or the floors, polishing furniture, and even cooking exhausted her. She had to take frequent rests in between and battle to catch her breath.

But when I asked her about it, she was always ready with an excuse. She was tired from staying up too late the night before; she had a bit of lumbago, she got up too fast, anything and everything but her owning up to the truth—that she hadn't been well for quite some time now.

Finally, on the third Sunday in August, I rose and dressed and went down, surprised I was up and ready before her, especially on a church day. When she finally appeared, she looked pale and very old, as old as Rip van Winkle after his extended sleep. She cringed a bit when she walked and held her hand against her side.

"I don't know what's come over me," she declared. "I haven't overslept like this for years."

"Maybe you can't cure yourself, Grandmère. Maybe your herbs and potions don't work on you and you should see a town doctor," I suggested.

"Nonsense. I just haven't found the right formula yet, but I'm on the right track. be back to myself in a day or two," she swore, but two days went by and she didn't improve an iota. One minute she would be talking to me and the next, she would be fast asleep in her chair, her mouth wide open, her chest heaving as if it were a struggle to breathe.

Only two events got her up and about with the old energy she used to exhibit. The first was when Grandpère Jack came to the house and actually asked us for money. I was sitting with Grandmère on the galerie after our dinner, grateful for the little coolness the twilight brought to the bayou. Her head grew heavier and heavier on her shoulders until her chin'-rested on her chest, but the moment Grandpère Jack's footsteps could be heard, her head snapped up. She narrowed her eyes into slits of suspicion.

"What's he coming here for?" she demanded, staring into the darkness out of which he emerged like some ghostly apparition from the swamp: his long hair bouncing on the back of his neck, his face sallow with his grimy gray beard thicker than usual, and his clothes so creased and dirty, he looked like he had been rolling around in them for days. His boots were so thick with mud, it looked caked around his feet and ankles.

"Don't you come any closer," Grandmère snapped. "We just had our dinner and the stink will turn our stomachs."

"Aw, woman," he said, but he stopped about a half-dozen yards from the galerie. He took off his hat and held it in his hands. Fishhooks dangled from the brim. "I come here on a mission of mercy," he said.

"Mercy? Mercy for who?" Grandmère demanded.

"For me," he replied. That nearly set her laughing. She rocked a bit and shook her head.

"You come here to beg forgiveness?" she asked.

"I came here to borrow some money," he said.

"What?" She stopped rocking, stunned.

"My dingy's motor is shot to hell and Charlie McDermott won't advance me any more credit to buy a new used one from him. I gotta have a motor or I can't earn any money guiding hunters, harvesting oysters, whatnot," he said. "I know you got something put away and I swear—"

"What good is your oath, Jack Landry? You're a cursed man, a doomed man whose soul already has a prime reservation in hell," she told him with more vehemence and energy than I had seen her exert in days. For a moment Grandpère didn't reply.

"If I can earn something, I can pay you back and then some right quickly," he said. Grandmère snorted.

"If I gave you the last pile of pennies we had, you'd turn from here and run as fast as you could to get a bottle of rum and drink yourself into another stupor," she told him. "Besides," she said, "we haven't got anything. You know how times get in the bayou in the summer for us. Not that you showed you cared any," she added.

"I do what I can," he protested.

"For yourself and your damnable thirst," she fired back.

I shifted my gaze from Grandmère to Grandpère. He really did look desperate and repentant. Grandmère Catherine knew I had my painting money put away. I could loan it to him if he was really in a fix, I thought, but I was afraid to say.

"You'd let a man die out here in the swamp, starve to death and become food for the buzzards," he moaned.

She stood up slowly, rising to her full five feet four inches of height as if she were really six feet tall, her head up, her shoulders back, and then she lifted her left arm to point her forefinger at him. I saw his eyes bulge with shock and fear as he took a step back.

"You are already dead, Jack Landry," she declared with the authority of a bishop, "and already food for buzzards. Go back to your cemetery and leave us be," she commanded.

"Some Christian you are," he cried, but continued to back up. "Some show of mercy. You're no better than me, Catherine. You're no better," he called, and turned to get swallowed up in the darkness from where he had come as quickly as he had appeared. Grandmère stared after him a few moments even after he was gone and then sat down.

"We could have given him my painting money, Grandmère," I said. She shook her head vehemently.

"That money is not to be touched by him," she said firmly. "You're going to need it someday, Ruby, and besides," she added, "he'd only do what I said, turn it into cheap whiskey.

"The nerve of him," she continued, more to herself than to me, "coming around here and asking me to loan him money. The nerve of him . . ."

I watched her wind herself down until she was slumped in her chair again, and I thought how terrible it was that two people who had once kissed and held each other, who had loved and wanted to be with each other were now like two alley cats, hissing and scratching at each other in the night.

The confrontation with my Grandpère drained Grandmère. She was so exhausted, I had to help her to bed. I sat beside her for a while and watched her sleep, her cheeks still red, her forehead beaded with perspiration. Her bosom rose and fell with such effort, I thought her heart would simply burst under the pressure.

That night I went to sleep with great trepidation, afraid that when I woke up, I would find Grandmère Catherine hadn't. But thankfully, her sleep revived her and what woke me the next morning was the sound of her footsteps as she made her way to the kitchen to start breakfast and begin another day of work in the loom room.

Despite the lack of customers, we continued our weaving and handicrafts whenever we could during the summer months, building a stock of goods to put out when the tourist season got back into high swing. Grandmère bartered with cotton growers and farmers who harvested the palmetto leaves with which we made the hats and fans. She traded some of her gumbo for split oak so we could make the baskets. Whenever it appeared we were bone-dry and had nothing to offer in return for craft materials, Grandmère reached deeper into her sacred chest and came up with something of value she had either been given as payment for a traiteur mission years before, or something she had been saving just for such a time.

Just at one of these hard periods, the second thing occurred to put vim and vigor into her steps and words. The postman delivered a fancy light blue envelope with a lace design on its edges addressed to me. It came from New Orleans, the return address simply Dominique's.

"Grandmère, I've got a letter from the gallery in New Orleans," I shouted running into the house. She nodded, holding her breath, her eyes bright with excitement.

"Go on, open it," she said, slipping into a chair. I sat at the kitchen table while I tore it open and plucked out a cashier's check for two hundred and fifty dollars. There was a note with it.

Congratulations on the sale of one of your pictures. I have some interest in the others and will be contacting you in the near future to see what else you have done since my visit.

Sincerely, Dominique

Grandmère Catherine and I just looked at each other for a moment and then her face lit up with the brightest, broadest smile I had seen her wear for months. She closed her eyes and offered a quick prayer of thanks. I continued to stare incredulously at the cashier's check.

"Grandmère, can this be true? Two hundred and fifty dollars! For one of my paintings!"

"I told you it would happen. I told you," she said. "I wonder who bought it. He doesn't say?"

I looked again and shook my head.

"It doesn't matter," she said. "Many people will see it now and other well-to-do Creoles will come to Dominique's to look for your work and he will tell them who you are; he will tell them the artist is Ruby Landry," she added, nodding.

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.