"I never said I was, Marianne."

"If anything, you're worse. You're a bastard child. That's what you are," she accused. The others nodded. Encouraged, she reached out to seize my arm and continue. "Paul Tate finally has shown some sense. He belongs with someone like Suzzette and certainly not a low-class Cajun like a Landry," she concluded.

I pulled away and brushed at my tears as I rushed from the girls' room. It was true—everyone thought Paul belonged with someone like Suzzette Daisy and thought they were the perfect couple. She was a pretty girl with long, light brown hair and stately features, but more important, her father was a rich oil man. I was sure Paul's parents were overjoyed at his choice of a new girlfriend. He'd have no trouble getting the car and going to dances with Suzzette.

Yet despite his apparent happiness with his new girlfriend, I couldn't help but detect a wistful look in his eyes when he saw me occasionally and especially at church. Starting a relationship with Suzzette, and the passage of more time since our split-up, finally began to calm him. I even thought he was close to speaking to me, but every time he seemed to be headed in that direction, something stopped him and turned him away again.

Finally, mercifully, the school year ended, and with it my daily contact with Paul, as slight as it had been. Outside of school he and I truly did live in two different worlds. He no longer had any reason to come my way. Of course, I still saw him at church on Sunday, but in the company of his parents and sisters, he especially wouldn't even look in my direction. Occasionally, I would hear what sounded like his motor scooter's engine and go running to my doorway to look out in anticipation and in the hope that I would see him pull into our drive just as he used to so many times before. But the sound either turned out to be someone else on a motorcycle or some old car passing by.

These were my days of darkness, days when I was so sad and tired that I had to fight to get out of bed each morning. Making everything seem worse and harder was the intensity with which the heat and the humidity greeted the bayou this particular summer. Everyday temperatures hovered near a hundred with humidity often only a degree or two less. Day after day the swamps were calm, still, not even the tiniest wisp of a breeze weaving its way up from the Gulf to give us any relief.

The heat took a great toll on Grandmère Catherine. More than ever, she was oppressed by the layers and layers of heavy humidity. I hated it when she had to walk somewhere to treat someone for a bad spider bite or a terrible headache. More often than not, she would return exhausted, drained, her dress drenched, her hair sticking to her forehead and her cheeks beet red; but these trips and the work she did resulted in some small income or some gifts of food for us and with the tourist trade dwindling down to practically nothing during the summer months, there wasn't much else.

Grandpère Jack wasn't any help. He stopped even his infrequent assistance. I heard he was hunting alligators with some men from New Orleans who wanted to sell the skins to make pocketbooks and wallets and whatever else city folk made out of the swamp creatures' hides. I didn't see him much, but whenever I did, he was usually floating by in his canoe or drifting in his dingy and guzzling some homemade cider or whiskey, satisfied to turn whatever money he had made from his gator hunting into another bottle or jug.

Late one afternoon, Grandmère Catherine returned from a treateur mission more exhausted than ever. She could barely speak. I had to rush out to help her up the stairs. She practically collapsed in her bed.

"Grandmère, your legs are trembling," I cried when helped her take off her moccasins. Her feet were blistered and swollen, especially her ankles.

"I'll be all right," she chanted. "I'll be all right. Just get me a cold cloth for my forehead, Ruby, honey."

I hurried to do so.

"I'll just lay here a while until my heart slows down," she told me, and forced a smile.

"Oh, Grandmère, you can't make these long trips anymore. It's too hot and you're too old to do it."

She shook her head.

"I must do it," she said. "It's why the good Lord put me here."

I waited until she fell asleep and then I left the house and poled our pirogue out to Grandpère's shack. All of the sadness and days of melancholy I had endured the past month and a half turned into anger and fury directed at Grandpère. He knew how hard it was for us during the summer months. Instead of drinking up his spare money every week, he should think about us and come around more often, I decided. I also decided not to discuss it with Grandmère Catherine, for she wouldn't want to admit I was right and she wouldn't want to ask him for a penny.

The swamp was different in the summer. Besides the waking of the hibernating alligators who had been sleeping with tails fattened with stores, there were dozens and dozens of snakes, clumps of them entwined together or slicing through the water like green and brown threads. Of course, there were clouds of mosquitos and other bugs, choruses of fat bullfrogs with gaping eyes and jiggling throats croaking and families of nutrias and muskrats scurrying about frantically, stopping only to eye me with suspicion. The insects and animals continually changed the swamp, their homes making it bulge in places it hadn't before, their webs linking plants and tree limbs. It made it all seem alive, like the swamp was one big animal itself, forming and reforming with each change of season.

I knew Grandmère Catherine would be upset that I was traveling alone through the swamp this later in the summer day, as well as being upset that I was going to see Grandpère Jack. But my anger had come to a head and sent me rushing out of the house to plod over the marsh and pole the pirogue faster than ever. Before long, I came around a turn and saw Grandpère's shack straight ahead. But as I approached, I slowed down because the racket coming from it was frightening.

I heard pans clanging, furniture cracking, Grandpère's howls and curses. A small chair came flying out the door and splashed in the swamp before it quickly sunk. A pot followed and then another. I stopped my canoe and waited. Moments later, Grandpère appeared on his galerie. He was stark naked, his hair wild, holding a bullwhip. Even at this distance, I could see his eyes were bloodshot. His body was streaked with dirt and mud and there were even long, thin scratches up his legs and down the small of his back.

He cracked the whip at something in the air before him and shouted before cracking it again. I soon understood he was imagining some kind of creature and I realized he was having a drunken fit. Grandmère Catherine had described one of them to me, but I had never seen it before. She said the alcohol soaked his brain so bad it gave him delusions and created nightmares, even in the daytime. On more than one occasion, he had one of these fits in the house and destroyed many of their good things.

"I used to have to run out and wait until he grew exhausted and fell asleep," she told me. "Otherwise, he might very well hurt me without realizing it."

Remembering those words, I backed my canoe into a small inlet so he wouldn't see me watching. He cracked the whip again and again and screamed so hard, the veins in his neck bulged. Then he caught the whip in some of his muskrat traps and got it so entangled, he couldn't pull it out. He interpreted this as the monster grabbing his whip. It put a new hysteria into him and he began to wail, waving his arms about him so quickly, he looked like a cross between a man and a spider from where I was watching. Finally, the exhaustion Grandmère Catherine described set in and he collapsed to the porch floor.

I waited a long moment. All was silent and remained so. Satisfied, he was unconscious, I poled myself up to the galerie and peered over the edge to see him twisted and asleep, oblivious to the mosquitos that feasted on his exposed skin.

I tied up the canoe and stepped onto the galerie. He looked barely alive, his chest heaving and falling with great effort. I knew I couldn't lift him and carry him into the house, so I went inside and found a blanket to put over him.

Then, I pulled in a deep fearful breath and nudged him, but his eyes didn't even flutter. He was already snoring. I went cold inside. All the hopes that had lit up were snuffed out by the sight and the stench rising off him. He smelled like he had taken a bath in his jugs of cheap whiskey.

"So much for coming to you for any help, Grandpère," I said furiously. "You are a disgrace." With him unconscious, I was able to vent my anger unchecked. "What kind of a man are you? How could you let us struggle and strain to keep alive and well? You know how tired Grandmère Catherine is. Don't you have any self-respect?

"I hate having Landry blood in me. I hate it!" I screamed, and pounded my fists against my hips. My voice echoed through the swamp. A heron flew off instantly and a dozen feet away, an alligator lifted its head from the water and gazed in my direction. "Stay here, stay in the swamp and guzzle your rotgut whiskey until you die. I don't care," I cried. The tears streaked down my cheeks, hot tears of anger and frustration. My heart pounded.

I caught my breath and stared at him. He moaned, but he didn't open his eyes. Disgusted, I got back into the pirogue and started to pole myself home, feeling more despondent and defeated than ever.

With the tourist trade nearly nonexistent and school over, I had more time to do my artwork. Grandmère Catherine was the first to notice that my pictures were remarkably different. Usually in a melancholy mood when I began, I tended now to use darker colors and depict the swamp world at either twilight or at night with the pale white light of a half moon or full moon penetrating twisted sycamores and cypress limbs. Animals stared out with luminous eyes and snakes coiled their bodies, poised to strike and kill any intruders. The water was inky, the Spanish moss dangling over it like a net left there to ensnare the unwary traveler. Even the spiderwebs that I used to make sparkle like jewels now appeared more like the traps they were intended to be. The swamp was an eerie, dismal, and depressing place and if I did include my mysterious father in the picture, he had a face masked with shadows.

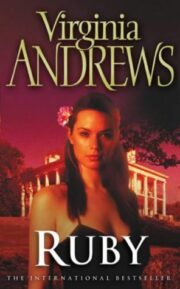

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.