About eleven o'clock Paul drove up on his motor scooter. Grandmère Catherine and I exchanged a quick look, but she said nothing more to me as Paul approached.

"Hello, Mrs. Landry," he began. "My cheek is practically all healed and my lip feels fine," he quickly added. The bruise had diminished considerably. There was just a slight pink area on his cheekbone. "Thanks again."

"You're welcome," Grandmère said, "but don't forget your promise to me."

"I won't." He laughed and turned to me. "Hi."

"Hi," I said quickly, and unfolded and folded a blanket so it would rest more neatly on the shelves of the stall. "How come you're not working in the cannery today?" I asked, without looking at him.

He stepped closer so Grandmère wouldn't hear.

"My father and I had it out last night. I'm not working for him anymore and I can't use the car until he says so, which might be never unless—"

"Unless you stop seeing me," I finished for him, then turned around. The look in his eyes told me I was right.

"I don't care what he says. I don't need the car. I bought the scooter with my own money, so I'll just ride around on it. All I care about doing is getting here to see you as quickly as I can. Nothing else matters," he declared firmly.

"That's not true, Paul. I can't let you do this to your parents and to yourself. Maybe not now, but weeks, months, even years from now, you'll regret driving your parents away from you," I told him sternly. Even I could hear the new, cold tone in my voice. It pained me to be this way, but I had to do it, I had to find a way to stop what could never be.

"What?" He smiled. "You know the only thing I care about is getting to be with you, Ruby. Let them adjust if they don't want to drive us apart. It's all their fault. They're snobby and selfish and—"

"No, they're not, Paul," I said quickly. His face hardened with confusion. "It's only natural for them to want the best for you."

"We've been over this before, Ruby. I told you, you're the best for me," he said. I looked away. I couldn't face him when I spoke these words. We had no customers at the moment, so I walked away from the stall, Paul trailing behind me as closely and as silently as my shadow. I paused at one of our cypress log benches and sat down, facing the swamp.

"What's wrong?" he asked softly.

"I've been thinking it all over," I said. "I'm not sure you're the best for me."

"What?"

Out in the swamp, perched on a big sycamore tree, the old marsh owl stared at us as if he could hear and understand the words we were saying. He was so still, he looked stuffed.

"After you left last night, I gave everything more thought. know there are many girls my age or slightly older who are already married in the bayou. There are even younger ones, but I don't just want to be married and live happily ever after in the bayou. I want to do more, be more. I want to be an artist."

"So? I would never stop you. I'd do everything I could to—"

"An artist, a true artist, has to experience many things, travel, meet many different kinds of people, expand her vision," I said, turning back to him. He looked smaller, diminished by my words. He shook his head.

"What are you saying?"

"We shouldn't be so serious," I explained.

"But I thought . . ." He shook his head. "This is all because I made a fool of myself last night, isn't it? Your grandmother is really very upset with me."

"No, she's not. Last night just made me think harder, that's all."

"It's my fault," he repeated.

"It isn't anyone's fault. Or, at least it isn't our fault," I added, recalling Grandmère Catherine's revelations last night. "It's just the way things are."

"What do you want me to do?" he asked.

"I want you to . . . to do what I'm going to do . . see other people, too."

"There's someone else then?" he followed, incredulous. "How could you be the way you were last night with me and the days and nights before that and like someone else?"

"There's not someone else just yet," I muttered.

"There is," he insisted. I looked up at him. His sadness was being replaced with anger rapidly. The softness in his eyes evaporated and a fury took its place. His shoulders rose and his face became as crimson as his bruised cheek. His lips whitened in the corners. He looked like he could exhale fire like a dragon. I hated what I was doing to him. I wished I could just vanish.

"My father told me I was a fool to put my heart and trust in you, in a—"

"In a Landry," I coached sadly.

"Yes. In a Landry. He said the apple doesn't fall far from the tree."

I lowered my head. I thought about my mother letting herself be used by Paul's father for his pleasure and I thought about Grandpère Jack caring more about getting money than what had happened to his daughter.

"He was right."

"I don't believe you," Paul shot back. When I looked at him again, I saw the tears that had washed over his eyes, tears of pain and anger, tears that would poison his mind against me. How I wished I could throw myself into his arms and stop what was happening, but I was thwarted and muzzled by reality. "You don't want to be an artist; you want to be a whore."

"Paul!"

"That's all, a whore. Well, go on, be with as many different men as you like. See if I care. I was crazy to waste my time on a Landry," he added and pivoted quickly, his boots kicking up the grass behind him as he rushed away.

My chin dropped to my chest and my body slumped on the cypress log bench. Where my heart had been, there was now a hollow cavity. I couldn't even cry. It was as if everything in me, every part of me had suddenly locked up, frozen, become as cold as stone. The sound of Paul's motor scooter engine reverberated through my body. The old marsh owl lifted his wings and strutted about nervously on the branch, but he didn't lift off. He remained there, watching me, his eyes filled with accusation now.

After Paul left our house, I got up. My legs were very shaky, but I was able to walk back to the roadside stall just as a carload of tourists pulled up. They were young men and women, loud and full of laughter and fun. The men went wild over the pickled lizards and snakes and bought four jars. The women liked Grandmère's handwoven towels and handkerchiefs. After they had bought everything they wanted and loaded their car, one of the young men paused and approached us with his camera.

"Do you mind if I take your pictures?" he asked. "I'll give you each a dollar," he added.

"You don't have to pay us for our pictures," Grandmère replied.

"Oh, yes, he does," I said. Grandmère Catherine raised her eyebrows in surprise.

"Fine," the young man said and dug into his pocket to produce the two dollars. I took them quickly. "Can you smile?" he asked me. I forced one and he snapped his photos. "Thanks," he said, and got into the car.

"Why did you make him give us two dollars, Ruby? We haven't taken money from tourists in the past." Grandmère asked me.

"Because the world is full of pain and disappointment, Grandmère, and I plan to do all I can from now on to make it less so for us."

She fixed her eyes on me thoughtfully. "I want you to grow up, but I don't want you to grow up with a hard heart, Ruby," she said.

"A soft heart gets pierced and torn more, Grandmère. I'm not going to end up like my mother. I'm not!" I cried and despite my firm and rigid stance, I felt my new wall start to crack.

"What did you say to young Paul Tate?" Grandmère asked. "What did you tell him to make him run off like that?"

"I didn't tell him the truth, but I drove him away, just as you said I should," I moaned through my tears. "Now, he hates me."

"Oh, Ruby, I'm sorry."

"He hates me!" I cried, and turned and ran from her.

"Ruby!"

I didn't stop. I ran hard and fast over the marshland, letting the bramble bushes slap and tear at my dress, my legs, and my arms. I was oblivious to pain; I ignored the ache in my chest and disregarded the puddles and the mud into which I repeatedly stepped. But after a while, the pain in my legs and the needles in my side brought me to a halt, and I could only walk slowly over the long stretch of marshland that ran alongside the canal. My shoulders heaved with my deep sobs. I walked and walked, past the dried domes of grass that were homes to the muskrats and nutrias, avoiding the inlets in which the small green snakes swam. Fatigued and drowning in many emotions, I finally stopped and gasped in air, my hands on my hips, my bosom rising and falling.

After a moment, my eyes focused on a clump of small sycamore trees just ahead. At first, because of its color and size, I didn't see it. But gradually, it formed in my field of vision, seemingly appearing like a vision. I saw a marsh deer watching me with curiosity. It had big, beautiful, but sad looking eyes and it stood as still as a statue.

Suddenly, there was a loud report, the explosion of a high caliber rifle came from the blind, and the deer's knees crumbled. It stumbled a moment in a desperate effort to maintain its stance, but a red circle of blood appeared on its neck and grew larger and larger as the blood emerged. The deer went down quickly after that and I heard the sound of two men cheering. A pirogue shot out from under a wall of Spanish moss and I saw two strangers in the front and Grandpère Jack poling from the rear. He had hired himself out to tourist hunters and brought them to their kill. As the canoe made its way across the pond toward the dead deer, one of the tourists handed the other a bottle of whiskey and they drank to celebrate their kill. Grandpère Jack eyed the bottle and stopped poling so they could give him a swig.

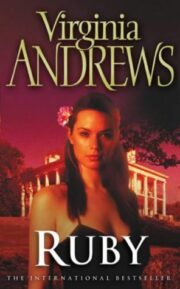

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.