"As you know we're Catholics; we don't go to no shack butchers and abort our pregnancies. I asked her who was the father and she just shook her head and ran from me. Later, when Grandpère Jack came home and heard, he went wild. He nearly beat her to death before I stopped him, but he got out of her who the father was," she said, and raised her eyes slowly.

Was that thunder I heard, or was it blood thundering through my veins and roaring in my ears?

"Who was it, Grandmère?" I asked, my voice cracking, my throat choking up quickly.

"It was Octavious Tate who had seduced her," she said, and once again it was as if thunder shook the house, shook the very foundations of our world and shattered the fragile walls of my heart and soul. I could not speak; I could not ask the next question, but Grandmère had decided I was to know it all.

"Grandpère Jack went to him directly. Octavious had been married less than a year and his father was alive then. Your Grandpère Jack was an even bigger gambler in those days. He couldn't pass up a game of bourré even though most times he was the one stuffing the pot. One time he lost his boots and had to walk home barefoot. And another time, he wagered a gold tooth and had to sit and let someone pull it out with a pliers. That's how sick a gambler he was and still is.

"Anyway, he got the Tates to pay him to keep things silent and part of the bargain was that Octavious would take the child and bring it up as his own. What he told his new wife and how they worked it out between them, we never knew, didn't care to know.

"I kept your mother's pregnancy hidden, strapping her up when she started to show in the seventh month. By then it was summer and she didn't have to attend school. We kept her here at the house most of the time. During the final three weeks, she stayed inside mostly and we told everyone that she had gone to visit her cousins in Iberia.

"The baby, a healthy boy, was born and delivered to Octavious Tate. Grandpère Jack got his money and lost it in less than a week, but the secret was kept.

"Up until now, that is," she said, lowering her head. "I had hoped never to have to tell you. You already know what your mother did later on. I didn't want you to think terrible of her and then think terrible of yourself.

"But I never counted on you and Paul . . . becoming more than just friends," she added. "When I saw you two kiss out by his car before, I knew you had to be told," she concluded.

"Then Paul and I are half brother and half sister?" I asked with a gasp. She nodded. "But he doesn't know any of this?"

"As I told you, we didn't know how the Tates dealt with it."

I buried my face in my hands. The tears that burned beneath my lids seemed to be falling inside me as well, making my stomach icy and cold. I shivered and rocked.

"Oh, God, how horrible, oh, God," I moaned.

"You see and understand why I had to tell you, don't you, Ruby dear?" Grandmère Catherine asked. I could feel how troubled she was by making the revelation, how much it bothered her to see me in such pain. I nodded quickly. "You must not let things go any further between the two of you, but it's not your place to tell him what I've told you. It's something his own father must tell him."

"It will destroy him," I said, shaking my head. "It will crack his heart in two, just as it has cracked mine."

"Then don't tell him, Ruby," Grandmère Catherine advised. I looked up at her. "Just let it all end."

"How, Grandmère? We like each other so much. Paul is so gentle and kind and—"

"Let him think you don't care about him anymore like that, Ruby. Let him go and he'll find another girlfriend soon enough. He's a handsome boy. Besides, his parents will only give him more grief if you don't, especially, his father, and you will only succeed in breaking the Tates apart."

"His father is a monster, a monster. How could he have done such a thing when he was married for such a short time?" I demanded, my anger overcoming my sadness for the moment.

"I make no excuses for him. He was a grown man and Gabrielle was just an impressionable young girl, but so beautiful, it didn't surprise me that grown men longed for her. The devil, the evil spirit that hovers in the shadows, crept over Octavious Tate day by day, I'm sure, and eventually found entrance into his heart and drove him to seduce your mother."

"Paul would hate him, he would hate his own father if he knew," I said vehemently. Grandmère nodded.

"Do you want to do that, Ruby? Do you want to be the one who puts enmity in his heart and drives him to despise his own father?" she asked softly. "And what will Paul feel about the woman he thinks is his mother? What will you do to that relationship, too?"

"Oh, Grandmère," I cried, and rose off the settee to throw myself at her feet. I embraced her legs and buried my face in her lap. She stroked my hair softly.

"There, there, my baby. You will get over the pain. You're still very young with your whole life ahead of you. You're going to become a great artist and have beautiful things." She put her hand under my chin and lifted my head so she could look into my eyes. "Now do you understand why I dream of you leaving the bayou," she added.

With my tears streaming down my cheeks, I nodded. "Yes," I said. "I do. But I never want to leave you, Grandmère."

"Someday you will have to, Ruby. It's the way of all things, and when that day comes, don't hesitate. Do what you have to do. Promise me you will. Promise," she demanded. She looked so anxious about it, I had to respond.

"I will, Grandmère."

"Good," she said. "Good." She sat back, looking as if she had just aged a year for every minute that passed. I ground the tears from my eyes with my small fists and stood up.

"Do you want something, Grandmère? A glass of lemonade, maybe?"

"Just a glass of cold water," she said, smiling. She patted my hand. "I'm sorry, honey," she said.

I swallowed hard and leaned down to kiss her on the cheek.

"It's not your fault, Grandmère. You have no reason to blame yourself."

She smiled softly at me. Then I got her the glass of water and watched her drink it. It seemed painful for her to do so, but she finished it and rose from her chair.

"I'm very tired, suddenly," she said. "I've got to go to bed."

"Yes, Grandmère. I will soon, too."

After she left, I went to the front door and looked out at where Paul and I had kissed good night.

We didn't know it then, but it was the last time we would ever kiss like that, the last time we would ever feel each other's heart beating and thrill to each other's touch. I closed the door and walked to the stairway, feeling as if someone I knew and loved with all my heart had just died. In a real sense that was true, for the Paul Tate I knew and loved before was gone and the Ruby Landry he had kissed and loved as well was lost. The sin that had given Paul life had reared its ugly head and taken away his love.

I dreaded the days that were now to follow.

That night I tossed and turned and woke from my sleep many times. Each time, my stomach felt as tight as a fist. I wished the whole day and night had just been a bad dream, but there was no denying Grandmère Catherine's dark, sad eyes. The vision of her face lingered behind my eyelids, reminding, reinforcing, confirming that all that had happened and all that I had learned was real and true.

I didn't think Grandmère Catherine had slept any better than I had, even though she had looked so exhausted before going to bed. For the first time in a long time, she was up and about only moments before me. I heard her shuffling past my room and opened the door to watch her make her way to the kitchen.

I hurried to go down to help her with our breakfast. Although the rainstorm of the night before had passed, there were still layers of thin, gray clouds across the Louisiana sky, making the morning look as dreary as I felt. The birds seemed subdued as well, barely singing and calling to each other. It was as if the whole bayou were feeling sorry for me and for Paul.

"Seems a Traiteur should be able to treat her own arthritis," Grandmère muttered. "My joints ache and my recipes for medicine don't seem to help."

Grandmère Catherine was not one to voice complaints about herself. I'd seen her walk miles in the rain to help someone and not utter a single syllable of protest. No matter what infirmity or hard luck she suffered, she always remarked that there were too many who were worse off.

"You don't drop the potato because hills and valleys suddenly appear on your road," she told me, which was a Cajun's way of saying you don't give up. "You bear the brunt; you carry the excess baggage, and you go on." I always felt she was trying to teach me how to live by example, so I knew how much pain she must be suffering to complain about it in my presence this morning.

"Maybe we should take a day off from the road stall, Grandmère," I said. "We've got my painting money and—"

"No," she said. "It's better to keep busy, and besides, we've got to be out there while there are still tourists in the bayou. You know we have enough weeks and months without anyone coming around to buy our things and it's hard enough to scrounge and scrape up a living then."

I didn't say it, because I knew it would only get her angry, but why didn't Grandpère Jack do more for us? Why did we let him get away with his lazy, swamp bum life? He was a Cajun man and as such he should bear more responsibility for his family, even if Grandmère was not pleased with him. I made up my mind I would pole out to his shack later and tell him what I thought.

Right after breakfast, I started to set up our roadside stall as usual while Grandmère prepared her gumbo. I saw the strain on her face as she worked and then carried things out, so I ran and got her a chair to sit on as quickly as I could. Despite what she had said, I wished it would rain hard and send us back into the house, so she could rest. But it didn't and just as she had predicted, the tourists began to come around.

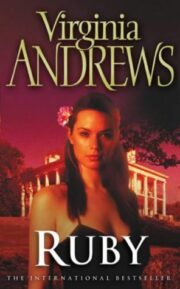

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.