All day Saturday, I debated about my hair. Should I wear it brushed down, tied with a ribbon in the back, or should I wear it up in a French knot? In the end I asked Grandmère to help me put my hair up.

"You have such a pretty face," Grandmère Catherine said. "You should wear your hair back more often. You're going to have a lot of nice boyfriends," she added, more to soothe herself than to please me, I thought. "So remember not to give away your heart too quickly." She took my hand into both of hers and fixed her eyes on me, eyes that looked sad and tired. "Promise?"

"Yes, Grandmère. Grandmère," I said, "are you feeling all right? You've looked very tired all day."

"Just that old ache in the back and my quickened heartbeat now and again. Nothing out of the ordinary," she said.

"I wish you didn't have to work so hard, Grandmère. Grandpère Jack should do more for us instead of drinking up his money or gambling it away," I declared.

"He can't do anything for himself, much less for us. Besides, I don't want anything from him. His money's tainted," she said firmly.

"Why is his money any more tainted than any other trapper's in the bayou, Grandmère?"

"His is," she insisted. "Let's not talk about it. If anything sets my heart beating like a parade drum, that does."

I swallowed my questions, afraid of making her sicker and more tired. Instead, I put on my dress and polished my shoes. Tonight, because the weather was unstable with intermittent showers and stronger winds, Paul was going to use one of his family's cars. He told me his father had said it was all right, but I had the feeling he hadn't told them everything. I was just too frightened to ask and risk not going to the dance. When I heard him drive up, I rushed to the door. Grandmère Catherine followed and stood right behind me.

"He's here," I cried.

"You tell him to drive slowly and be sure you're home right after the dancing," Grandmère said.

Paul rushed up to the galerie. The rain had started again, so he held an umbrella open for me.

"Wow, Ruby, you look very pretty tonight," he said, then saw Grandmère Catherine step out from behind me. "Evening, Mrs. Landry."

"You get her home nice and early," she ordered.

"Yes, ma'am."

"And drive very carefully."

"I will."

"Please, Grandmère," I moaned. She bit down on her lip to keep herself silent and I leaned forward to kiss her cheek.

"Have a good time," she muttered. I ran out to slip under Paul's umbrella and we hurried to the car. When I looked back, Grandmère Catherine was still standing in the doorway looking out at us, only she looked so much smaller and older to me. It was as if my growing up meant she was to grow older, faster. In the midst of my excitement, an excitement that made the rainy night seem like a star-studded one, a small cloud of sadness touched my thrilled heart and made it shudder for a second. but the moment Paul started driving away, I smothered the trepidation and saw only happiness and fun ahead.

The fais dodo hall was on the other side of town. All furniture, except for the benches for the older people, was moved out of the large room. In a smaller, adjoining room, large pots of gumbo were placed on tables. We didn't have a stage as such, but platforms were used to provide a place for the musicians, who played the accordion, the fiddle, the triangle, and guitars. There was a singer, too.

People came from all over the bayou, many families bringing their young children as well. The little ones were put in another adjoining room to sleep. In fact, fais dodo was Cajun baby talk for go-to-sleep, meaning put all the small kids to bed so the older folks could dance. Some of the men played a card game called bourré while their wives and older children danced what we called the Two-step.

Paul and I no sooner entered the fais dodo hall than I could hear the whispers and speculations on people's lips—what was Paul Tate doing with one of the poorest young girls in the bayou? Paul didn't seem as aware of the eyes and the whispering as I was, or if he was, he didn't care. As soon as we arrived, we were out on the dance floor. I saw some of my girlfriends gazing at us with green eyes, for just about every one of them would have liked Paul Tate to bring her to a fais dodo.

We danced to one song after another, applauding loudly at the end of each song. Time passed so quickly that we didn't realize we had danced nearly an hour before we decided we were hungry and thirsty. Laughing, feeling as if there were no one else here but the two of us, we headed for refreshments. Both of us were oblivious to the group of boys who followed along, lead by Turner Browne, one of the school bullies. He was a stout, bull-necked seventeen-year-old with a shock of dark brown hair and large facial features. It was said that his family went back to the flatboat polers who had navigated the Mississippi long before the steamboat. The polers were a rough, violent bunch and the Brownes were thought to have inherited those traits. Turner lived up to the family reputation, getting into one brawl after another at school.

"Hey, Tate," Turner Browne said after we had gotten our bowls of gumbo and sat at the corner of a table. "Your mommy know you're out slumming tonight?"

All of Turner's friends laughed. Paul's face turned crimson. Slowly, he stood up.

"I think you'd better take that back, Turner, and apologize."

Turner Browne laughed.

"What'cha gonna do, Tate, tell your daddy on me?"

Again, Turner's friends laughed. I reached up and tugged on Paul's sleeve. He was red-faced and so angry he seemed to give off smoke.

"Ignore him, Paul," I said. "He's too stupid to bother with."

"Shut your mouth," Turner said. "At least I know who my father is."

At that, Paul shot forward and tackled the much larger boy, knocking him to the floor. Instantly, Turner's friends let up a howl and formed a circle, around Paul and Turner, blocking out anyone who might have rushed to put a quick end to it. Turner was able to roll over Paul and pin him down by sitting on his stomach. He delivered a punch to Paul's right cheek. It swelled up almost instantly. Paul was able to block Turner's next punch, just as the older men arrived and pulled him off Paul. When he stood up, Paul's lower lip was bleeding.

"What's going on here?" Mr. Lafourche demanded. He was in charge of the hall.

"He attacked me," Turner accused, pointing at Paul. "That's not the whole truth," I said. "He—"

"All right, all right," Mr. Lafourche said. "I don't care who did what. This sort of thing doesn't go on in my hall. Now get yourselves out of here. Go on, Browne. Move yourself and your crew before I have you all locked up."

Smiling, Turner Browne turned and led his bunch of cronies away. I brought a wet napkin to Paul and dabbed his lip gently.

"I'm sorry," he said. "I lost my temper."

"You shouldn't have. He's so much bigger."

"I don't care how big he is. I'm not going to allow him to say those things to you," Paul replied bravely. With his cheek scarlet and a little swollen, I could only cry for him. Everything had been going so well; we were having such a good time. Why was there always someone like Turner Browne to spoil things?

"Let's go," I said.

"We can still stay and dance some more."

"No. We'd better get something on your bruises. Grandmère Catherine will have something that will heal you quickly," I said.

"She'll be disappointed in me, angry that I got into a fight while I was with you," Paul moaned. "Damn that Turner Browne."

"No, she won't. She'll be proud of you, proud of the way you came to my defense," I said.

"You think so?"

"Yes," I said, although I wasn't sure how Grandmère would react. "Anyway, if she can fix it so your face doesn't look so bad, your parents won't be as angry, right?"

He nodded and then laughed.

"I look terrible, huh?"

"Not much better than someone who wrestled an alligator, I suppose."

We both laughed and then left the hall. "Turner Browne and his friends were already gone, off to guzzle beer and brag to each other, I imagined, so there was no more trouble. It was raining harder when we drove back to the house. Paul pulled as close as he could and then we hurried in under the umbrella. The moment we stepped through the door, Grandmère Catherine looked up from her needlework and nodded.

"It was that bully, Turner Browne, Grandmère. He—"

She lifted her hand, rose from her seat, and went to the counter where she had some of her poultices set out as if she had anticipated our dramatic arrival. It was eerie. Even Paul was speechless.

"Sit down," she told him, pointing to a chair. "After I treat him, you can tell me all about it."

Paul looked at me, his eyes wide, and then moved to the seat to let Grandmère Catherine work her miracles.

4

Learning to Be a Liar

"Here," Grandmère Catherine told Paul, "keep this pressed against your cheek with one hand and this pressed against your lip with the other." She handed him two warm cloths over which she had smeared one of her secret salves. When Paul took the cloths, I saw the knuckles on his right hand were all bruised and scraped as well.

"Look at his hand, too, Grandmère," I cried.

"It's nothing," Paul said. "When I was rolling around on the floor—"

"Rolling around on the floor? At the fais dodo?" Grandmère asked. He nodded and then started to speak. "We were having some gumbo and—"

"Hold those tight," she ordered. While he was holding the cloth against his lip, he couldn't talk, so I spoke for him, quickly.

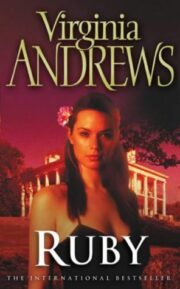

"Ruby" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Ruby". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Ruby" друзьям в соцсетях.