“The Church of Rome, Madam, is polluted.”

“I do not find it so. My conscience tells me it is the true Church.”

“Conscience must be supported by knowledge, Madam. You are without the right knowledge.”

“You forget that, though I am as yet young in years, I have read much and studied.”

“So had the Jews who crucified Christ.”

“Is it not a matter of interpretation? Who shall be judge who is right or wrong?”

Knox’s answer was: “God!” And by God he meant himself.

Mary’s eyes appealed to her brother: Oh, take this man away. He wearies me.

John Knox would not be silenced. There he stood in the center of the chamber, his voice ringing to the rafters; and everything he said was a condemnation, not only of the Church of Rome, but of Mary herself.

For he had seen her weakness. She was tolerant. Had she been as vehement as he was, he would have spoken more mildly, and he would have seized an early opportunity to leave Scotland. But she was a lass, a frivolous lass, who liked better to laugh and play than to force her opinions on others.

Knox would have nothing to fear from the Queen. He would rant against her; he would set spies to watch her; he would put his own interpretation on her every action, and he would do his utmost to drive her from the throne unless she adopted the Protestant Faith.

Mary had risen abruptly. She had glanced toward Flem and Livy, who had been sitting in the window seat listening earnestly and anxiously to all that had been said. The two girls recognized the signal. They came to the Queen.

“Come,” said Mary, “it is time that we left.”

She inclined her head slightly toward Knox and, with Flem and Livy, passed out of the room.

BY THE LIGHT of flickering candles the Queen’s apartment might well have been set in Chenonceaux or Fontainebleau. She was surrounded by her ladies and gentlemen, and all were dressed in the French manner. Only French was spoken. From Paris had come her Gobelins tapestry, and it now adorned the walls. On the floor were rich carpets, on the walls gilt-framed mirrors. D’Amville and Montmorency were beside her; they had been singing madrigals, and Flem and Beaton were in an excited group who were discussing a new masque they intended to produce.

About the Court the Scottish noblemen quarreled and jostled for honors. The Catholic lords sparred continually with the Protestant lords. On the Border the towns were being ravished both by the English and rival Scottish clans.

In the palace were the spies of John Knox, of Catherine de Médicis and of Elizabeth of England. These three powerful people had one object: to bring disaster to the Queen of Scots.

Yet, shut in by velvet hangings and Gobelins tapestry, by French laughter, French conversation, French flattery and charm, Mary determined to ignore what was unpleasant. She believed her stay there would be short; soon she would make a grand marriage—perhaps with Spain. But in the meantime she would make it pass as merrily and in as lively a fashion as was possible; and so during those weeks life was lived gaily within those precincts of Holy rood which had become known as “Little France.”

TWO

IN THE SMALL ROOM ADORNED WITH THE FINEST OF HER French tapestries, Mary was playing chess with Beaton. Flem was at her embroidery and Livy and Seton sat reading quietly.

Mary’s thoughts were not really on the game. She was troubled, as she was so often since she had come to Scotland. There were times when she could shut herself away in Little France, but she could not long succeed in shutting out her responsibilities. These Scots subjects of hers—rough and lusty—did not seem to wish to live in peace with one another. There were continual feuds and she found herself spending much time in trying to reconcile one with another.

Beaton said that Thomas Randolph, the English ambassador, told her that affairs were managed very differently in the English Court, and that the Tudor Queens frown was enough to strike terror into her most powerful lords. Mary was too kindly, too tolerant.

“But what can I do?” Mary had demanded. “I am powerless. Would to God I were treated like Elizabeth of England!” She was sure, she said, that Thomas Randolph exaggerated his mistress’s power.

“He spoke with great sincerity,” Beaton had ventured.

But Beaton was inclined to blush when the Englishman’s name was mentioned. Beaton was ready to believe all that man said.

Mary began to worry about Beaton and the Englishman. Did the man—who was a spy as all ambassadors were—seek out Beaton, flatter her, perhaps make love to her, in order to discover the Queens secrets?

Dearest Beaton! She must be mad to think of Beaton as a spy! But Beaton could unwittingly betray, and it might well be that Randolph was clever enough to make her do so.

In France, the Cardinal of Lorraine had been ever beside Mary, keeping from her that which he did not wish her to know. Now she was becoming aware of so much of which she would prefer to remain in ignorance. Her brother James and Maitland stood together, but they hated Bothwell. The Earl of Atholl and the Earl of Errol, though Catholics, hated the Catholic leader Huntley, the Cock o’ the North. There was Morton whose reputation for immorality almost equaled that of Bothwell; and there was Erskine who seemed to care for little but the pleasures of the table. There was the quarrel between the Hamilton Arran and Bothwell which flared up now and then and had resulted in her banishing Bothwell from the Court, on Lord James’s advice, within a few weeks of her arrival, in spite of all his good service during the voyage.

She was disturbed and uncertain; she was sure she would never understand these warlike nobles whose shadows so darkened her throne.

She recalled now that warm September day when she had made her progress through the capital. She had been happy then, riding on the white palfrey which had with difficulty been procured for her, listening to the shouts of the people and their enthusiastic comments on her beauty. She had thought all would be well and that her subjects would come to love her.

But riding on one side of her had been the Protestant Lord James, and on the other the Catholic Cock o’ the North; and the first allegorical tableau she had witnessed on that progress through the streets had ended with a child, dressed as an angel, handing her, with the keys of the city, the Protestant Bible and Psalter—and she had known even then that this was a warning. She, who was known to be a Catholic, was being firmly told that only a Protestant sovereign could hold the key to Scotland.

Moreover it had been a great shock, on arriving at Market Cross, to find a carved wooden effigy of a priest in the robes of the Mass fixed on a stake. She had blanched at the sight, seeing at once that preparations had been made to burn the figure before her eyes. She had been glad then of the prompt action of the Cock o’ the North—an old man, but a fierce one—who had ridden ahead of her and ordered the figure to be immediately removed. To her relief this had been done. But it had spoiled her day. It had given her a glimpse of the difficulties which lay ahead of her.

She had returned from the entry weary, not stimulated as she used to be when she and François rode through the villages and towns of France. But she had determined to make a bid for peace and, to show her desire for tolerance, had appointed several of the Reformers to her government. Huntley, the Catholic leader, was among them with Argyle, Atholl and Morton as well as Châtelherault. Her brother, Lord James Stuart, and Lord Maitland were the leaders; and in view of the service he had rendered her, she could not exclude Bothwell, though that wild young man had succeeded in getting himself dismissed from Court—temporarily, of course. She had no wish to be severe with anyone.

Beaton looked up from the board and cried: “Checkmate, I think, Your Majesty. I think Your Majesty’s thoughts were elsewhere, or I should never have had so easy a victory.”

“Put away the pieces,” said the Queen. “I wish to talk. Now that we have our rooms pleasantly furnished, let us have a grand ball. Let us show these people that we wish to make life at Court brighter than it has hitherto been. Perhaps, if we can interest them in the pleasant things of life, they will cease to quarrel so much about rights and wrongs and each others opinions.”

“Let us have a masque!” cried Flem, her eyes sparkling. She was seeing herself dressed in some delightful costume, mumming before the Court, which would include the fascinating Maitland—surely, thought Flem, the most attractive man on earth—no longer young, but no less exciting for that.

Livy was thinking of tall Lord Sempill who had made a point of being at her side lately, surely more than was necessary for general courtesy, while Beaton’s thoughts were with the Englishman who had such wonderful stories to tell of his mistress, the Queen of England. Only Seton was uneasy, wondering whether she could tell the Queen that one of the priests had been set upon in the streets and had returned wounded by the stones which had been thrown at him; and that she had heard there was a new game to be played in the streets of Edinburgh, instigated by John Knox and called “priest-baiting”.

The Queen said: “Now, Seton! You are not attending. What sort of masque shall it be?”

“Let there be singing,” said Seton. “Oh, but I forgot… Your Majesty’s choir is short of a bass.”

“There is a fine bass in the suite of the Sieur de Moretta,” said Livy.

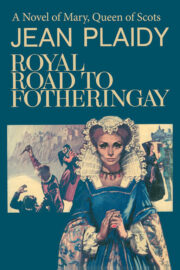

"Royal Road to Fotheringhay" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Road to Fotheringhay". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Road to Fotheringhay" друзьям в соцсетях.