She was not pleased by the Englishmen’s arrogant attitude toward her. They implied that their Queens will should be Mary’s. She was bewildered, inexperienced in dealing with such situations alone, so she obeyed those inclinations dictated by her pride.

Her uncles and Henri of France had assured her that she was the rightful heir to England. At the moment she was in decline but she would not always be so. One day she might be Queen of Spain and then these Englishmen would think twice before addressing her as they did now.

She said: “My lords, I shall not sign the treaty of Edinburgh.”

“It has been signed in Edinburgh, Madame.”

“But it would seem that it does not become valid until you have my signature.”

This they could not deny.

Here was another of those moments of folly, the result of hurt pride and ignorance.

“Then, my lords, I will say to you that I cannot give you the signature for which you ask. I must have time to ponder the matter.”

Exasperated, they left her. They wrote to their mistress; and Elizabeth of England vowed that she would never forgive—and never trust—her Scottish kinswoman as long as that beautiful head remained on those elegant shoulders.

SHE TRAVELED down to Rheims to stay for a while with her aunt, Renée de Guise, at the Abbey Saint-Pierre-les-Dames. Renée, the sister of those ambitious uncles, was quite unlike them. Perhaps she, a member of that mighty and ambitious family, had felt the need to escape to a nunnery in order to eschew that ambition which was at the very heart of the family’s tradition.

There was quietness with Renée, but Mary did not want quiet. She was restless.

Renée, knowing that Mary was troubled, tried to help her through prayer. Mary realized that Renée was suggesting that if she too would shun ambition—as Renée had done—she might find peace in a life of dedication to prayer and service to others.

Mary, emotional in the extreme, thought for a short time—a very short time—of the peace to be found within convent walls. But when she looked in her mirror and saw her own beautiful face, and thought of dancing and masking with herself the centre of attention, when she remembered the admiration she had seen in the eyes of those men who surrounded her, she knew that whatever she had to suffer in the future—even if it meant returning to Scotland—it was the only life that would be acceptable to her.

With Renée she did become more deeply religious; she was even fired with a mission. Her country was straining toward Calvinism, and she would bring it back to the Church which she felt to be the only true one.

“But not,” she told Renée, “with torture and the fire, not with the thumbscrews and the rack. Perhaps I am weak, but I cannot bear to see men suffer, however wrong they are. Even though I knew the fires of hell lay before them, I could not torment myself by listening to their cries, and if I ever countenanced the torture, I believe those cries would reach me, though I were miles away.”

Renée smiled at Mary’s fierceness. She said: “You are Queen of a country that is strongly heretic. It is your duty to return to it and save it from damnation. You are young and weak … as yet. But the saints will show you how to act.”

Mary shuddered and, when she thought of that land in the grip of Calvin and his disciple Knox, she prayed that King Philip would agree to her marriage with his son, or perhaps, better still, she need never leave her beloved France. If Charles broke free of his mother’s influence, his first act would be to marry Mary Stuart.

To Rheims at this time came her relations on a visit to the Cardinal. The Duke arrived with his mother, and there followed Mary’s two younger uncles, the Due d’Aumale and the Marquis d’Elboeuf.

There were many conferences regarding Mary’s marriage into Spain.

The Cardinal took her to his private chamber and there he tried to revive their old relationship. But she had grown up in the last month and some of her innocence had left her. The Cardinal seemed different. She noticed the lines of debauchery on his face, and how could she help knowing that his love for her depended largely on her ability to give him that which he craved: power? She was no longer the simple girl she had been.

She was aloof and bewildered. It was no use, his drawing her gently to him, laying his fine hands on her, soothing and caressing, bringing her to that state of semi-trance when her will became subservient to his. She saw him more clearly now, and she saw a sly man. She already knew that he was a coward; and she believed that his love for her had diminished in proportion to her loss of power and usefulness.

Marriage with France. Marriage with Spain. They were like two bats chasing each other around in his brain; and he was the wily cat not quite quick enough to catch one of them. But perhaps there was another—more agile, more happily placed than he. Catherine continually foiled him. He was wishing he could slip the little “Italian morsel” into her goblet, as she was no doubt wishing she could slip it into his.

If he could but remove Catherine he would have Mary married to Charles in a very short time.

To Rheims came the news which sent the spirits of the whole family plunging down to deep depression.

Philip of Spain sent word that he would find it inconvenient, for some time to come, to continue with the negotiations for a marriage between his son Don Carlos and Mary Stuart.

Catherine de Médicis stood between Mary and the King of France. She had—by working in secret—insinuated herself between Mary and the heir of Spain.

Catherine was going to bring about that which she had long desired: the banishment from France of the young and beautiful Queen who had been such a fool as to show herself no friend to Catherine de Médicis.

Word came from Lord James Stuart. He was coming to France to persuade his sister that it was time she returned to her realm.

SO SHE WAS to leave the land she loved. The Court buzzed with the news. This was farewell to the dazzling Mary Stuart.

She tried to be brave, but there was a great fear within her.

She told her Marys: “It will only be for a short time. Soon I shall marry. Do not imagine we shall stay long in Scotland; I am sure that soon King Philip will continue with the arrangements for my marriage to Don Carlos.”

“It will be fun to go to Scotland for a while,” said Flem.

“They’ll soon find a husband for you,” declared Beaton.

While she too could think thus Mary felt almost gay. It would only be a temporary exile, and she would take with her many friends from the Court of France.

Henri de Montmorency, who had now become the Sieur d’Amville since the return of his father to power, whispered to her: “So France is to lose Your Majesty!”

She was hurt by his happy expression. She said tartly: “It would seem that you are one of those who rejoice in my departure.”

“I do, Your Majesty.”

“I pray you let me pass. I was foolish enough to think you had some regard for me. But that, of course, was for the Queen of France.”

He bent his head so that his eyes were near her own. “I rejoice,” he said, “because I have heard that I am to accompany your suite to Scotland.”

Her smile was radiant. “Monsieur…,” she began. “Monsieur d’Amville… I…”

He took her hands and kissed them passionately. For a moment she allowed this familiarity but she quickly remembered that she must be doubly cautious now. As Queen she could more easily have afforded to be lax than now when she was stripped of her dignity.

She said coolly: “I thank you for your expression of loyalty, Monsieur d’Amville.”

“Loyalty… and devotion,” he murmured, “my most passionate devotion.”

He left her then, and when he entered his suite he was smiling to himself. One of his attendants—a poet, Pierre de Chastelard—rose to greet him.

“You are happy today, my lord,” said Chastelard.

D’Amville nodded and continued to smile. “Shall I tell you why, Chastelard, my dear fellow? I have long loved a lady. Alas, she was far beyond my aspirations. But now I have gone up and she has come down. I think we have come to a point where we may most happily meet.”

“That is worthy of a poem,” suggested Chastelard.

“It is indeed. I have high hopes.”

“The lady’s name, sir?”

“A secret.”

“But if I am to sing her praises in verse…”

“Well then, I’ll whisper it, but tell no one that Henri de Montmorency is deep in love with the beautiful Mary Stuart who is going to be in need of comfort when she reaches her barbaric land. I shall be there to give it. That is why you see me so gay.”

“Now I understand, my lord. It is enough to make any man gay. She is a beautiful creature and was most chaste, it would seem, when married to our King François. Even Brantôme—who can usually find some delicious tidbit of scandal concerning the seemingly most virtuous—has had nothing but praise to sing of the Queen of Scots.”

“She is charming,” said D’Amville. “And it is true that she is chaste. What is it about her… tell me that. You are something of a connoisseur, my friend. She is innocent and yet… and yet…”

“And yet… and yet…,” cried Chastelard. “My lady fair is innocent and yet… and yet… and yet…”

The two young men laughed together.

“May all good luck attend you,” said Chastelard. “I envy you from the bottom of my heart.”

“My hopes soar. She will be desolate. She will be ready to love anyone who is French while she is in that dreary land. You shall accompany me, my dear Chastelard; you shall share in my triumph … at secondhand, of course!”

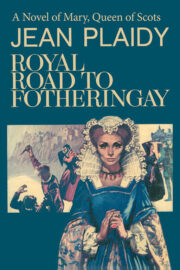

"Royal Road to Fotheringhay" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Road to Fotheringhay". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Road to Fotheringhay" друзьям в соцсетях.