Queen Catherine was beside her, pressing her large body gently forward, reminding her that she, Mary, must stand aside now as once Catherine had stood aside for her.

Queen Catherine wished her to know in this moment of bitter grief that Mary was no longer first lady in the land. Catherine was in the ascendant; Mary was in decline.

SIX

IN THE SHROUDED CHAMBER THE YOUNG WIDOW SAT ALONE. Her face was pale beneath the white coif; the flowing robes of her white dress fell to the floor; even her shoes were white. The chamber was lighted only by tapers and it seemed like a tomb to Mary.

She paced the room. She had no tears left. Since her first coming to the Court of France, François had been her friend and her devoted slave. Had she been at times a little too arrogant, a little too certain of his devotion? If she could only have him back now, how she would assure him of this love which she only knew went so deep since she had lost him.

What tragic changes had overtaken her life! She thought of her uncles as they had been on the day of François’s death, standing with her, one on either side of her, while the nobles of the Court, led by Queen Catherine, went to the apartments of the little Charles to do homage to the new King.

They had said nothing to her, those uncles; but she knew they were disappointed in her. There should have been a child, their eyes accused her. A child would have changed everything. Their sinister implication was: If François could not give you a child, there were others who could.

What was honor to those uncles of hers? What was morality? All that mattered was the power of Guise and Lorraine; and, according to them, she had failed in her duty toward her maternal house.

What would become of her?

She smoothed the folds of the deuil blanc, apprehensive of the unknown doom which must soon overtake her.

DURING THOSE first weeks of mourning she must see no one except her attendants and members of the royal family.

They came to visit her—Charles, the nine-year-old King, and Catherine, his mother.

Mary knelt before the boy, who, in his newfound dignity, commanded: “Rise, dear Mary.”

She should have been comforted by the love she saw in his eyes, but she realized that, young as he was, the love he bore her was not that of a brother. The young King’s eyes grew feverish as they studied the white-clad figure. It was as though he were saying: “I am the King of France now that François is dead. There is nothing between us now.”

Could this thing come to pass? Was it possible that she might again be Queen of France? This boy—this unbalanced child who was now the King—wished it; her uncles would do all in their power to bring it about, for if she married Charles the Guises’ power would be unchanged. The only difference would be that in place of gentle François, Mary would have a new husband, wild Charles.

Catherine was closely watching her son’s face. She said: “It is sad for you, my daughter, to be thus alone. Forty days and forty nights … it is a long time to mourn.”

“It seems a short time, Madame,” said Mary. “I shall mourn the late King all my life.”

Catherine puffed her lips. “You are young yet. When you return to your own country you will mayhap have another husband to love.”

Mary could not hide the fear which showed in her face. That was what she dreaded more than anything—to leave the land which she had come to look upon as her own, to sail away to the dismal country of which she had bleak memories and was reminded every now and then when the crude-mannered Scots came to the Court of France. She could not bear to lose her husband, her position and her country at one blow. That would be too much to endure.

“Madame, I should wish to remain here. I have my estates in France. I would retire from the Court if necessary.”

The King said: “It is not our wish that you should do so. We wish you to stay here, dear Mary.”

“Your Majesty is good to me. It is a great comfort to me to know of your kindness.”

“Dearest Mary, I have always loved you,” said the King.

His mother had gripped his shoulder so hard that he winced and, turning angrily, he scowled at her. Mary watched them and she saw the fear which suddenly came into the boy’s face.

Catherine laughed loudly. “The King feels tender toward you,” she said. “He remembers the love his brother bore you. We shall be desolate when you leave us.”

“Mary is not going to leave us,” cried the King wildly. He took Mary’s hand and began to kiss it passionately. “No, Mary, you shall stay. I say so… I say so… and I am the King.”

The red blood suffused the King’s cheeks; his lips began to twitch.

“I cannot have the King agitated,” said Catherine looking coldly at Mary, as though she were the cause of his distress.

“Perhaps if he speaks his mind freely,” said Mary, “he will be less agitated.”

“At such a time! And my little son with such greatness thrust upon him, and he but a child… scarcely out of his nursery! Oh, I thank God that he has a mother to stand beside him at this time, to guide him, to counsel him, to give freely of her love and the wisdom she has gleaned through experience … for he has need of it. He has need of it indeed.”

“I am the King, Madame,” persisted Charles.

“You are the King, my son, but you are a child. The ministers about your throne will tell you that. Your mother tells you. Your country expects wisdom of you far beyond your nine years. You must listen to the counsels of those who wish you well for, believe me, my son, there are many in this realm who would be your deadly enemies if they dared.”

A terrible fear showed in the little boy’s face and Mary wondered what stories of the fate which would befall an unwanted king had been poured into his ears.

Charles stammered: “But… but everybody will be glad if Mary stays here. Everybody loves Mary. They were so pleased when she married François.”

“But Mary has her kingdom to govern. They are waiting for her, those countrymen of hers. Do you think they will allow her to stay here forever? I doubt it. Oh, I greatly doubt it. I’ll swear that at this moment they are preparing a great welcome for her. She has her brothers there, remember. James Stuart… Robert and John Stuart and hundreds… nay, thousands of loyal subjects. Her neighbor and sister across the border will rejoice, I am sure, to know that her dear cousin of Scotland is not so far away as hitherto.”

Mary cried out: “I am so recently a widow. I have lost a husband whom I loved dearly. And you come to me—”

“To tell you of my sympathy. You were his wife, my dear, but I was his mother.”

“I loved him. He and I were together always.”

“He and I were together even longer. He was with me before the rest of the world ever saw him. Think of that. And ask yourself whether your grief can be greater than mine.”

“Madame, it would seem so,” said Mary impulsively.

Catherine laid a hand on her shoulder. “My dear Queen of Scotland, I am an old woman; you are a young one. When you have reached my age you will doubtless have learned that grief should be controlled—not only for the good of the sufferer but for those about her.”

“You cannot care as I do.”

“Can grief be weighed?” asked Catherine, turning her eyes to the ceiling. “You are young. There will be suitors and you will find a new husband… one who, I doubt not, will please you better than my dear son did.”

“I beg of you… stop!” implored Mary.

Charles cried: “Mary… Mary… you shall not go. I’ll not allow it. I am the King and I will marry you.”

Catherine laughed yet again. “You see the King of France is but a child. He knows not the meaning of marriage.”

“I do!” declared Charles hotly. “I do.”

“You shall marry at the right time, my darling. And then who knows who your bride will be.”

“Madame, it must be Mary. It must.”

“My son—”

Charles stamped his foot; his twitching fingers began to pull at his doublet and the golden fringe came away in his hand. He flung it from him and turned his blazing eyes on his mother. “It shall be Mary! I want Mary. I love Mary.”

He threw himself at the young widow, flung his arms about her waist and buried his hot quivering face in the white brocade of her gown.

“It is so touching,” said Catherine. “Come, my dear little King. If this is your wish… well then, you are a king and a king’s wishes are not to be ignored. But to speak of this … so soon after your brother has died and is scarce cold in his grave … it frightens me. You want your brother’s wife. I beg of you keep quiet on such a matter for, with your brother so recently dead, it is a sin. Why, you will be afraid tonight when the candles are doused and your apartment is in darkness. You will be afraid of your brother’s accusing ghost.”

Charles had released Mary. He was staring at his mother and biting his lips; his hands began to pull once more at his doublet.

Catherine put her arm about him and held him against her.

“Do not tremble, my son. All will be well. Your mother has that which will protect you from evil spirits. But she needs your collaboration in this. Do not put into words thoughts which could bring disaster to you.”

Mary cried out: “Madame, I am mourning my husband. I would wish to be alone.”

“You poor child. It is true. You are mourning. This is not the time to remind you that, as Dowager Queen of France, you are no longer in a position to order the Queen-Mother of France from your apartment. We understand that it is the extremity of your grief which has made you forget this little detail. We know that when you emerge from your mourning you will fully realize your changed position. There, my child, do not let your grief overwhelm you. You have had many happy years with us here in France. If, by some ill chance, you should have to leave us, remember you will be going to your own country. It is not France, we know, but you will love it the more because it is yours. You will be a neighbor of your cousin of England—”

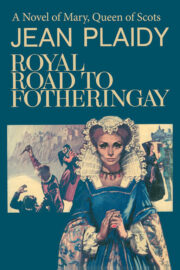

"Royal Road to Fotheringhay" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Road to Fotheringhay". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Road to Fotheringhay" друзьям в соцсетях.