The Duke ranted: “By this treaty, by a single stroke of the pen, all the Italian conquests of thirty years are surrendered, except the little marquisate of Saluzzo. Sire, shall we throw away Bress, Bugey, Savoy… Piedmont… all these and others? Shall we restore Valenza to Spain, Corsica to Genoa, Monteferrato to—”

“You need not proceed,” said the King coldly. “We need peace. We must have peace. You would have us go on until we exhaust ourselves in war. It is not the good of France which concerns you, Monsieur, but the glory of Guise and Lorraine.”

“Guise and Lorraine are France, Sire,” declared the bold Duke. “And Frances shame is their shame.”

The King turned abruptly away. It was time that reliable old ally and enemy of the Guises the Constable de Montmorency was back at Court.

There were other good things to come to France through this treaty. When it was signed, Philip of Spain and Henri of France would stand together against the heretic world. They could make plans for the alliance of their two countries; and such plans would contain, as they invariably did, contracts for royal marriages.

THERE CAME that never-to-be-forgotten day in June. There was no one, in that vast crowd which had gathered in the Rue St. Antoine near Les Tournelles where the arena had been set up for the tournament, who would ever forget it. It was a day which, by a mere chance, changed the lives of many people and the fate of a country.

The pale-faced Princess Elisabeth was there—a sixteen-year-old bride who had not yet seen the husband she was shortly to join, and whom she had married by proxy a few days earlier. The great Philip of Spain, she had been told, did not come for his brides; he sent for them. So the Duke of Alva had stood proxy for Philip, and the ceremony which had made her Philip’s wife had taken place. She was grateful for the haughty pride of Spanish kings which allowed her this small grace.

It was a frightened bride who watched the great events of that summer’s day.

Princess Marguerite, the King’s sister, was present. She was to marry the Duke of Savoy—which marriage had also been arranged with the signing of the treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis. The Duke of Savoy was present on this fateful day with his gentlemen brilliant in their red satin doublets, crimson shoes and cloaks of gold-embroidered black velvet, for this tournament was to be held in his honor.

All the nobility of France had come to pay respect to the future husband of the Princess Marguerite and the Spanish envoys of Elisabeth’s husband.

The Dauphin and the Dauphine came to the arena together in a carriage which bore the English coat of arms, and as they rode through the crowds, the heralds cried: “Make place! Make place for the Queen of England!”

The Constable de Montmorency was back in France, and Henri, his son, had married Mademoiselle de Bouillon, the granddaughter of Diane de Poitiers.

Did Mary care? She was a little piqued. He had sworn he would be bold; he had sworn that he would never marry, since he could not marry Mary.

Mary laughed. It was all a game of make-believe. She had been foolish to take anyone seriously.

Queen Catherine took her place in the royal gallery at the arena. Her face was not quite as expressionless as usual, for during the preceding night she had had uneasy dreams, and although the sun was shining in the Rue St. Antoine and the crowd was loyal, she was conscious of a deep depression.

The jousting began and the noble Princes excelled themselves. Mary was proud to watch the skill of her uncle the Duke of Guise and to hear the people’s warm acclamation of their hero.

The Duke of Alva, stern representative of his master, sat beside Elisabeth and applauded. The Count of Nassau, William of Orange, who had accompanied Alva, took part in the jousting.

There came that moment when the King himself rode out—a brilliant figure in his armor, his spurs jeweled, his magnificent white horse rearing—to meet his opponent. The people roared their loyal greeting to their King.

How magnificently Henri acquitted himself that day! His horse—a gift from the bridegroom-to-be, the Duke of Savoy—carried him to victory.

The King had acquitted himself with honor. The people had roared their approval. But he would go in once more. He would break one more lance.

The Dukes of Ferrara and Nemours were trying to dissuade him but he felt like a young man again. He had turned to the box in which sat Diane. Diane lifted her hand. The Queen half rose in her seat. But the King had turned away. He had signed to the Seigneur de l’Orges, a young captain of the Scottish Guards. The Captain hesitated, and then the King was calling for a new lance.

There was wild cheering as the King rode out a second time and began to tilt with the young Captain.

It was all over in less than a minute. The Captain had touched the King on the gorget; the Captains lance was splintered and the King was slipping from his horse, his face covered with blood.

There was a hushed silence that seemed to last a long time; and then people were running to where the King lay swooning on the grass.

THE KING WAS DYING. He had spoken little since he had fallen in the joust. He had merely insisted that the Captain was not to be blamed in any way because a splinter from his lance had brought about the accident. He had obeyed the King and had tilted when he had no wish to do so; he had carried himself like a brave knight and valiant man-at-arms. The King would have all remember that.

In the nurseries there was unusual quiet, broken only by sudden outbreaks of weeping.

Little Hercule cried: “When will my Papa be well? I want my Papa.”

The others comforted him, but they could not comfort themselves. Margot, whose grief, like all her emotions, was violent, shut herself into her apartment and made herself ill with weeping.

Mary and Elisabeth, François and Charles sat together, but they dared not speak for fear of breaking down. Mary noticed an odd speculative look in Charles’s eyes as he watched his brother. A King was dying, and when one King died another immediately took his place. The pale sickly boy would soon be King of France, but for how long?

Edouard Alexandre—Henri—was with his mother. She needed all the comfort he could give her. As she embraced him she told herself that he would take the place in her heart of the dying man. She was sure that the King was dying, because she knew such things.

And at last came the summons to his bedside. He was past speech and they were all thankful that he was past his agonies; he lay still and could not recognize any of them. They waited there, standing about his bedside until he ceased to breathe.

In a room adjoining the bedchamber all the leading men of France were gathering. The Cardinal was there with his brother, the Duke, and they both noticed that the glances which came their way were more respectful than they had ever been before, and that they themselves were addressed as though they were kings.

When it was all over, the family left the bedside—François first, apprehensively conscious, through his grief, of his new importance. Catherine and Mary were side by side, but when they reached the door, Catherine paused, laid a hand on Mary’s shoulder and pushed her gently forward.

That was a significant gesture. Queen Catherine was now only the Queen-Mother; Mary Stuart took first place as Queen of France.

FIVE

THE QUEEN OF FRANCE! THE FIRST LADY IN THE LAND! SHE was second only to the King, and the King was her devoted slave. Yet when she remembered that this had come about through the death of the man whom she had come to regard as her beloved father, she felt that she would gladly relinquish all her new honors to have him back.

François was full of sorrow. He had gained nothing but his father’s responsibilities, and dearly he had loved that father. So many eyes watched him now. He was under continual and critical survey. Terrifying people surrounded him and, although he was King of France, he felt powerless to escape from them. Those two men who called themselves his affectionate uncles held him in their grip. It seemed to him that they were always present. He dreamed of them, and in particular he dreamed of the Cardinal; he had nightmares in which the Cardinal figured, his voice sneering: “Lily-livered timorous girl… masquerading as a man!” Those scornful words haunted him by day and night.

There was one other whom he feared even more. This was his mother. If he were alone at any time she would come with all speed to his apartments and talk with him quietly and earnestly. “My dearest son… my little King… you will need your mother now.” That was the theme of all she said to him.

He felt that he was no better than a bone over which ban dogs were fighting.

His mother had been quick to act. Even during her period of mourning she had managed to shut out those two men. She had said: “The King is my son. He is not a King yet; he is merely a boy who is grieving for his father. I will allow no one to come near him. Who but his mother could comfort him now?”

But her comfort disturbed him more than his grief, and he would agree to anything if only she would go away and leave him alone to weep for his father. Mary could supply all the comfort he needed, and Mary alone.

Mary’s uncles came to the Louvre. They did not ask for an audience with the Queen of France; there could be no ceremonies at such a time, said the Cardinal, between those who were so near and dear. He did not kneel to Mary; he took her in his arms. The gesture indicated not only affection, but mastery.

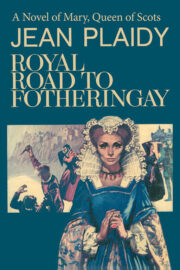

"Royal Road to Fotheringhay" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Road to Fotheringhay". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Road to Fotheringhay" друзьям в соцсетях.