Even the children noticed the change in her. The only one who did not seem to notice was Queen Catherine.

MARY LAY in bed; she could not sleep. She was suffering from pains which were not unfamiliar to her. She had eaten more than usual. She had such a healthy appetite, and she looked upon it as a duty to set a good example to François and Elisabeth who pecked at their food. The meal, presided over by Madame d’Humières and the Maréchal, had been much as usual. There were joints of veal and lamb; there were geese, chickens, pigeons, hares, larks and partridges; and Mary had done justice to all, with the result that, although there was to be a grand ball, she had had to retire early on account of her pains.

There had been some amusement about this ball because it had been arranged by the Queen and, oddly enough, the Constable de Montmorency had helped her with the arrangements. Young as she was, Mary was very intelligent and eager to learn all she could concerning Court matters; and with her four little Marys to assist her she could not help being aware of the tension which was inevitable in a Court where the Queen was submitted to perpetual humiliation, and the Kings mistress enjoyed all—and more—of those honors which should have been the Queens.

With the aging mistress sick at Anet—some said dying—that tension must increase. Would the Queen seek to regain some of her rights? Would some beautiful and ambitious lady seek to fill Diane’s place?

François and Elisabeth and little Claude might have watched the ball from one of the galleries. The French children would have enjoyed that more than mingling with the guests, but Mary would have wished to be with the dancers in a dazzling gown, her chestnut hair flowing, and all the gentlemen paying her laughing compliments and speaking of the enchantress she would become when she grew up. But alas, she was too sick to attend and must lie in bed instead.

Janet Fleming had talked continually of the ball, but Mary had felt too sick to listen. She had drunk the posset Queen Catherine had given her, and afterward had felt some misgivings. She had heard rumors about the Queens Italian cupbearer who had been torn asunder by wild horses when the King’s elder brother had died—of poison, some said, and others added: poison administered by Catherine de Médicis. Mary could not rid herself of the idea that Catherine wished her ill.

“Here,” Catherine had said, “this is what I call my gourmands dose. Do you know what Your Scottish Majesty is suffering from? A surfeit of goose-flesh, like as not. You have been overgreedy at the table.”

Mary had grown hot with indignation as Catherine had bent over to look into her face.

“You’re flushed,” said Catherine. “Is it a fever, or have I upset your dignity? The truth can be as indigestible as gooseflesh, my dear Reinette.”

And Mary had had to swallow the hideous stuff and lie in bed nursing a sore stomach while others danced.

It was near midnight but she could not sleep. She could hear the sound of music from the great ballroom.

Before going to the ball Janet Fleming had come into the apartment to show Mary her costume. Everyone was to be masked. Those were the Queens orders. The idea of the Queen and the Constable planning a ball! The whole Court was rocking with amusement. They would not miss Madame Diane tonight… not even the King.

“How I wish I could be with you,” sighed the little Queen.

“Has her Majesty’s posset done you no good then?”

“I am not sure that she meant it to. She hates me because I would not have Madame de Paroy in the nurseries.”

“You are a bold creature, darling Majesty, to go against the Queen of France.”

“Would you want Paroy in the nurseries?”

“Holy Mother of God, indeed I would not! Why, if she knew that the King had shown me … a little friendship, Heaven alone knows what she might tell the Queen. But… my tongue runs away with me and I shall be late for the ball.”

Mary put her arms round her aunt’s neck and kissed her. “Come and see me when the ball is over. I shall want to hear all about it,” said Mary.

So now she lay in bed waiting for the ball to be over.

She slept for a while, and when she awoke it was to silence. So the ball was over and her aunt had not come as she had promised. Faint moonlight shone through the windows, lighting the room. She sat up in bed, listening. Her pains had gone and she felt well and wide awake. But she was angry; she always was when she suspected she had been treated as a child. Lady Fleming had no doubt come in to tell her about the ball and, finding her asleep, had tiptoed away—just as though she were a baby.

Mary got out of bed and, putting a wrap about her shoulders, crept across the room to that small chamber in which Lady Fleming slept. She drew back the curtains of the bed. It was empty. Lady Fleming had not yet come up, although the ball was over.

Mary got into Janet’s bed to wait for her. She waited for a long time before she fell asleep; it was beginning to grow light when she was awakened by Janet’s returning.

Mary sat up in bed and stared at her aunt. She was wearing the costume she had worn at the ball, but it appeared to be crumpled and was torn in several places.

“What is it?” asked Mary.

“Hush! For the love of the saints do not wake anybody.” Janet began to take off the costume.

“But what has happened?” insisted Mary. “You look as though you have been set upon by robbers and yet are rather pleased about it.”

“You must tell no one of this, as you love your Fleming. You should not be here. You should be punished for wandering from your bed in the night. The Queen would punish you.”

“Perhaps she would punish you, too, for wandering in the night. I command you to tell me what has happened to you.”

Janet got into bed and put her arms about Mary. “What if another has commanded silence?” she said with a laugh.

“I am the Queen …”

“Of Scotland, my dearest. What if I had received a higher command?”

“The Queen… Queen Catherine?”

“Higher than that!” Lady Fleming kissed the Queen of Scots. “I am so happy, darling. I am the happiest woman in France. One day I shall be able to serve you as I should wish. One day you shall ask me for something you want, and I will perhaps, through the Kings grace, be able to give it to you.”

Mary was excited. Here was one of the mysteries which occurred in the lives of grown-up people; here was a glimpse into the exciting world in which one day she would have a part to play.

“There is one thing I will ask you now,” she said. “It is never to allow that dreary de Paroy to come near the nursery.”

“That I can promse you,” said Janet gleefully. “She is banished from this day.”

They lay together smiling, each thinking of the glorious future which lay ahead of her.

MARY FORGOT the excitement of the Court for a while. With her four friends she went to stay with her grandmother at Meudon. Her grandfather, Duke Claude, was very ill and not expected to live. She knew that soon her uncle François would be the Duke of Guise and head of the house. But she did not see him. It was her uncle, Cardinal Charles, with whom she spent much of her time.

They would walk about the estate together and the Cardinal’s eyes would gleam as they watched her. He studied her so closely that Mary blushed for fear he would find some fault in her. There were occasions when he would take her into his private chamber; she would sit on his knee and he would fondle her. He frightened her a little, while he fascinated her; her wide eyes would stare, almost involuntarily, at those long slim fingers which ceaselessly caressed her. She did not know whether she liked or hated those caresses. They fascinated yet repelled. Sometimes he would make her look into his face, and it was as though he were making her subject to his will. His long light eyes with the dark lashes were so beautiful that she wanted to look at them, although she was afraid; they were tender and malicious, gentle and cruel; and beneath them were faint shadows. His mouth was straight and long; it was the most beautiful mouth she had ever seen when it smiled—and it smiled often for her.

There was a delicious odor about his person; it clung to his linen. He bathed regularly; he was, it was said, the most fastidious gentleman of France. Jewels glittered on his hands, and the colors of those jewels were tastefully blended. Her grandparents were in some awe of him and seemed to have almost as much respect for him as they had for Uncle François.

“Always obey your Uncle François and your Uncle Charles,” she was continually told.

That was what they all wished to impress upon her. Even her new brother—whom she discovered in her grandparents’ house—the Duc de Longueville, the son of her mother by her first husband, hinted and implied that it was her duty.

Everyone was telling her that the most important thing in the world was the power of the Guises, and as she played with her Marys she could not completely forget it. She felt like a plant in a forcing house on those occasions in the perfumed chamber of the Cardinal when he talked to her of her duty and how she must make young François her completely devoted slave so that he gave way to her in all things.

“When you are older,” said the Cardinal, putting his hands on her shoulders and pressing her small body to his, “when you begin to bud into womanhood, then, my sweet and beautiful niece, you must learn how to make the Dauphin entirely yours.”

“Yes, Monsieur le Cardinal.”

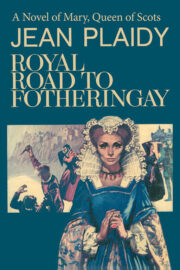

"Royal Road to Fotheringhay" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Road to Fotheringhay". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Road to Fotheringhay" друзьям в соцсетях.