“Oh, no! They will be hurt!” Alarmed, I ran toward the place where they’d disappeared, trailed by the remaining dogs.

The runt reappeared first, now colored an all-over brown. As I reached him, he gave himself a vigorous shake, spattering my skirt with mud. I could not help myself. I burst out laughing and reached down to lift his warm, filthy, wriggling little body into my arms. Ecstatic at this show of affection, he licked my face.

And so it was, for the second time in my life, that I remained oblivious to the presence of the king, accompanied by a band of his retainers, until His Grace stood not a foot away from me.

King Henry cleared his throat.

I looked up and froze. Dumbstruck, I clutched the small dog closer to my bosom. I had the mad idea that I must protect him from the king.

“Your Majesty,” Father said, bowing low. “May I present my youngest daughter, Audrey Malte.”

I continued to stare at the king, taking in his appearance bit by bit. He was so very splendid to look at that I did not think to curtsey until Father caught my forearm and jerked me downward.

In full sunlight, King Henry the Eighth dazzled the eye. The jewels set into his doublet and his plumed cap reflected the brightness of the day. The rings he wore on every finger glittered, too. And yet, had he been clad in the roughest, undecorated homespun, he’d still have awed onlookers with his magnificence.

Taller by a head than any man in his company, he was broad of shoulder and chest and sturdy of leg. No jewel could outshine the radiance of his nimbus of bright red-gold hair. Its brilliant shade was mirrored in his full beard. Only his eyes lacked gemlike qualities, being a muted blue-gray, but he had an intense and penetrating gaze.

He was also smiling.

“Rise, Audrey,” the king commanded. Then he turned to my father, clapping him on the back as he straightened from his obeisance and causing him to stagger a little. “And good morrow to you, Malte. Well met.”

They began to walk together along the same graveled path Father and I had been following when we encountered the dogs. I looked around for the rest of the pack and spotted them frolicking in one of the newly planted beds. One was digging with wild abandon. The king ignored these antics, apparently unconcerned with the destruction.

Reluctant to be left behind, I joined the king’s entourage, walking behind His Grace and my father. I looked down at the puppy I still held cradled in my arms. Soft brown eyes gazed back at me, full of trust and affection. Belatedly, I noticed that he wore a decorative collar made of red velvet and kid. One of the badges King Henry used—the Tudor rose—was attached to it.

Anthony Denny, the courtier who had brought the king’s message to the tailor shop, fell into step beside me. “That pup you are holding is a called a glove beagle,” he said. “The breed takes its name from the fact that even when full grown, they fit into the palm of a heavy leather hunting glove.”

“Are they lapdogs for ladies, then?” I asked.

“They are most commonly used to hunt rabbits. They ride along on a hunt, usually in a saddlebag, until the larger hounds run the prey to the ground. Then they are released to continue the chase through the underbrush.”

I had never heard of such a thing, but then I knew nothing of hunting, with or without the use of dogs.

Ahead of us, the king continued his conversation with my father, speaking to him in a companionable way that surprised me. No man was the equal of the king. King Henry, as head of the church in England, was only a trifle less to be revered than God Himself. Surely only noblemen were supposed to be on such familiar terms with His Grace.

I considered the evidence before my eyes and came to a conclusion. Father regularly saw His Grace stripped down to his linen—in order that he might fit the king for new clothes. This enforced intimacy must have created a bond between them.

The glove beagles, tired of ravaging through the flower beds, came hurtling after the king. Although he smiled indulgently at the pack, he ordered that they be taken back to their kennel.

“I will take that one now,” one of His Grace’s henchmen said, reaching for the little dog I still held.

“Could I not keep him with me just a little longer?” I asked.

The pup stared up at me with a pleading expression in his dark brown eyes and my heart melted. I darted a glance at the king and quailed when I saw that he was watching me. I feared I had offended him, or broken some rule about how to behave at court, and hastily dropped my gaze.

Heavy footsteps approached, crunching on the gravel, until King Henry stood right in front of me. “Would you like to keep him, Audrey?” he asked.

“More than anything,” I whispered, daring to meet his eyes.

His Grace must have seen the look in mine a thousand times before. Petitioners of all ages and stations in life flocked to court daily to ask for this boon or that. But with me the king was generous.

“Take him as our gift to you, young Audrey,” King Henry said. “Feed him on bread, not meat. That will discourage him from developing hunting instincts. And keep him on a leash or in a fenced yard when you take him out of doors, lest he run off and become lost.”

“I will take most excellent care of him, Your Grace,” I promised, thrilled beyond measure.

Satisfied, the king nodded and straightened. I barely noticed when His Grace left us a few minutes later, along with his escort. I was too busy playing with my new friend.

5

April 1538

I named the glove beagle Pocket, since he was small enough for me to carry in the pocket I wore tied around my waist. Because this pocket was hidden beneath my skirt—reached through a purpose-cut placket—Pocket caused more than one person to start and stare when he poked his head out without warning and announced himself in that strange baying bark that was distinctive to his breed. Mother Anne dubbed it a howl.

Elizabeth and Muriel responded to the little dog much as I had, with instant adoration. He returned their affection. Winning over Mother Anne took longer, nearly a week. Only Bridget refused to be charmed. She was still sulking because I had been chosen to meet the king and she had not.

A month after my visit to Whitehall, I was sleeping soundly when a harsh whisper jerked me awake.

“They are speaking of you,” Bridget hissed into my ear. “Come with me now.”

Still groggy, I allowed myself to be lured from the bedchamber. For once, I left Pocket behind. He was curled into a ball at the foot of the bed, lost in puppy dreams.

Following my sister, I crept quietly down the narrow staircase. Halfway to the lower level, when the rumble of Father’s voice reached me, I tried to pull back, but Bridget was relentless. She caught my arm in a tight grip and all but dragged me the rest of the way.

I knew where she was taking me. From a young age, she had made a habit of concealing herself behind the wall hanging in the hall—an embroidered scene of a picnic in a forest glade—to eavesdrop on Father and Mother Anne.

For one terrifying moment, we were exposed in the doorway and as we scuttled toward this hiding place, our white linen smocks shining like beacons as they caught the candlelight. Then we were safe in the stifling darkness. Neither Father nor Mother Anne had glanced our way.

Father was pacing. I could hear the slap of his slippered feet against the floor as he came close to the wall hanging and then moved away again. After a bit, he spoke.

“The court is a dangerous place for a young girl.”

“Then keep Audrey at home,” Mother Anne replied. The whisper of fabric against fabric told me she held an embroidery frame in her lap. She was calm where Father sounded agitated.

“I have no choice. I must obey the king.”

The news that King Henry wanted me to return to court surprised me. It irritated Bridget. She pinched me. Twice.

Father’s voice faded as he moved away. I missed a few words. And then he was talking about a recent outbreak of violence among the courtiers. “It has been as deadly as any plague,” he complained. “I do not know what spawned it, but there have been brawls, duels, and even murders, all within the verge.”

“The verge?” Mother Anne asked.

“That is the ten-mile radius that surrounds the person of the king. As you know, the king and his courtiers move about a good deal, but wherever King Henry is, that is the court and the verge moves with it.”

Father was always being called upon to travel to different palaces. I already knew many of their names—Greenwich and Whitehall, Richmond and Woodstock and Worksop. And Windsor Castle, where I had once lived. There were many other royal houses, too, smaller ones that the king visited when he went on his annual progress.

“Audrey is my responsibility,” Father said.

“And you do well by her.” A little silence ensued. “Whitehall is but a short distance from London,” Mother Anne pointed out. “You need not remain for more than a few hours at a time.”

“If the court were always at Whitehall Palace, there would be no problem.”

“Surely His Grace does not expect you to bring Audrey with you to the more distant palaces. Greenwich, mayhap, but that is not so very far away, either.”

“Nor are Richmond and Hampton Court,” he admitted.

“From any of those palaces, you can bring her home again before nightfall. She will sleep safe in her own bed.”

“And what of the times when I am obliged to leave her alone in the chamber set aside for my workroom? I cannot take her with me into His Grace’s bedchamber.”

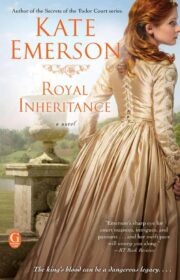

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.