BRIDGET MALTE

Bridget Malte was the daughter of John Malte, the king’s tailor, and his first wife. Most accounts call her his youngest daughter. By 1545, she had married John Scutt, a much older man, and given birth to a son, Anthony. Bridget and John Scutt were named overseers of John Malte’s will. After the family moved to Somerset, Scutt gained a reputation for mistreating his wife. When he died suddenly, there were whispers of poison. The whispers grew louder when Bridget remarried a fortnight after her husband’s death, taking as her second husband Edward St. Loe, the son of a local landowner. Later it came out that Bridget was three months pregnant with St. Loe’s child at the time of the marriage, but two months after they wed, on November 30, 1557, it was Bridget who died suddenly. Six months after that, Edward St. Loe married her stepdaughter, Margaret Scutt. All this gave rise to suspicion but no proof of murder. The inquisition postmortem was held on August 9, 1558. In the Chatsworth House Archives there is an account of a lawsuit in which Bridget is described as “a verye lustye yonge woman.”

ELIZABETH MALTE

Elizabeth Malte may not have been a Malte at all. She was certainly the daughter of Anne Malte, second wife and widow of John Malte (d. 1547), royal tailor, because Elizabeth and her husband were executors of Anne’s will. Elizabeth is not, however, mentioned in John Malte’s will. By then, Elizabeth was probably already married to Thomas Hilton (Hylton/Hulton), usually identified as the illegitimate son of William Hilton, who served as the king’s tailor before John Malte.

JOHN MALTE

John Malte was the king’s tailor until late 1546. The Malte house was in Watling Street in the parish of St. Augustine at Paul’s Gate. In 1541, Malte’s worth was set at two thousand marks and he was assessed £33 6s 8d in the London Subsidy Roll for Bread Street Ward. John Malte wrote his will on September 10, 1546, and it was proved June 7, 1547. He left bequests to his two married daughters, his two married stepdaughters by his first wife (I reduced this to one), his unmarried bastard daughter, and the foundling child left at his gate. His second wife, Anne, survived him.

MURIEL MALTE

Muriel Malte was the daughter of John Malte, the king’s tailor, and his first wife. In 1545, she married John Horner. In 1544, his father had purchased Cloford, Somersetshire, and John Malte purchased the manor of Podimore Milton, Somersetshire. Both properties were given to the young couple on their marriage. They had three sons: William, Thomas, and Maurice. Muriel died on March 9, 1548.

KATHRYN PARR

Henry VIII’s last queen attempted to reunite all the royal children at Ashridge during the summer progress of 1543. After the king’s death, she moved to her dower house at Chelsea Manor, where she maintained her own household. I have no evidence that she even knew Audrey Malte, but she certainly knew John Harington. As one of Thomas Seymour’s gentlemen, he would have been party to Seymour’s courtship of Kathryn and their later marriage. The queen dowager died in 1548.

JOHN SCUTT

John Scutt or Skutt was one of the royal tailors from 1519 to 1547, making clothing for all six of Henry VIII’s wives and also for private clients. Scutt was master of the Merchant Taylors’ Company in 1536. He was a widower with a young daughter, Margaret, when he married Bridget Malte, who appears to have been his neighbor in Bread Street Ward (parish of St. Augustine at Paul’s Gate). His worth was recorded at two thousand marks in 1541 and he was assessed £33 6s 8d. Scutt was granted arms on November 12, 1546. After the death of Henry VIII he retired to the manor of Stanton Drew, Somerset. He died in 1557. There was some speculation that his wife might have poisoned him.

THOMAS SEYMOUR

It is believed that Henry VIII was aware that Thomas Seymour and Kathryn Parr had tender feelings for each other after Kathryn’s second husband, Lord Latimer, died and that the king deliberately sent Seymour out of the country on diplomatic missions. Seymour’s hasty marriage to the queen dowager, his inappropriate behavior toward Princess Elizabeth, and his clumsy attempts to influence his nephew King Edward VI, and possibly to kidnap him, led to his downfall. He was executed for treason on March 10, 1549.

MARY SHELTON

Mary Shelton was the daughter of Sir John Shelton of Shelton, Norfolk, and Anne Boleyn, the sister of Queen Anne Boleyn’s father. A number of scholars argue that Mary Shelton was the king’s mistress in 1535 and also a candidate to become Henry’s fourth wife. I find the logic of this unconvincing. The mistress of 1535, known to history as “Madge,” was more likely to have been Mary’s older sister Margaret. The single mention of Mary Shelton as one of two ladies in whom the king was interested in 1538 comes in a letter that says nothing about marriage. The comment could as easily refer to the king’s choice of one of the two as his next mistress. What we do know to be true about Mary is that she was friends with Lady Margaret Douglas, Lady Mary Howard, Duchess of Richmond, and the duchess’s brother, Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey. She contributed to and edited the “Devonshire Manuscript,” a collection of poems, some of them original, that was passed around among members of their circle. Two of the poems suggest that Sir Thomas Wyatt pursued Mary and was rejected by her. Of course, Wyatt was married at the time. Mary may have been in attendance upon Queen Catherine Howard. After Catherine’s arrest, she spent most of the next year with her friends Mary Howard and Margaret Douglas at Kenninghall in Norfolk, Mary Howard’s home. She fell in love with Thomas Clere, one of the Earl of Surrey’s close friends. They intended to marry but were prevented by Clere’s death on April 14, 1545. Clere made her his principal heir and she is mentioned in the elegy Surrey wrote to Clere. Sometime in 1546, Mary wed Sir Anthony Heveningham, by whom she had several children. It is as Lady Heveningham that Surrey wrote to her while she was staying at the house of her brother, Jerome Shelton, formerly part of the priory of St. Helen, and this letter led to the suggestion that she be questioned after Surrey was arrested for treason. After Heveningham died, Mary wed Philip Appleyard. She was probably the Lady Heveningham at court in 1558–59. She died in 1571.

SIR RICHARD SOUTHWELL

Sir Richard Southwell is the villain of this piece. I can’t say for certain how he behaved toward Audrey Malte, although he did negotiate with John Malte for her marriage to his illegitimate son, but he did murder a man in 1532 and he did give evidence to the Privy Council that led directly to the Earl of Surrey’s arrest and execution in 1547. He also had a hand in the downfall of two other important figures at the court of Henry VIII—Sir Thomas More and Thomas Cromwell. His weak chin is immortalized in a sketch and portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger. Southwell fell out of favor at court after the death of Edward VI. No earlier than 1559, he married his longtime mistress and had one more child by her. This child, although legitimate, was a girl. Richard Darcy, alias Richard Southwell the Younger, remained his father’s principal heir. Southwell died in 1564.

RICHARD DARCY, ALIAS SOUTHWELL

Sir Richard Southwell’s illegitimate son studied at Cambridge and later entered Lincoln’s Inn. His betrothal to Audrey Malte was thwarted by her marriage to John Harington. He later married twice, the first time around 1555, and had numerous children. He died in 1600.

For more information on the women on this list, please see their entries at http://www.KateEmersonHistoricals.com/TudorWomenIndex.htm.

READING GROUP GUIDE

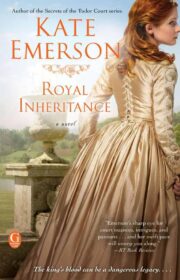

ROYAL

Inheritance

BY KATE EMERSON

About This Guide

This reading group guide for Royal Inheritance includes an introduction, discussion questions, and ideas for enhancing your book club. The suggested questions are intended to help your reading group find new and interesting angles and topics for your discussion. We hope that these ideas will enrich your conversation and increase your enjoyment of the book.

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.