I assured him she was. “She is to be allowed to walk for exercise twice a day in the privy garden and also in the great chamber adjacent to her lodgings.”

Jack sent a scornful look at the four walls that contained him. “Then she is fortunate indeed. Fresh air is a luxury here, as is open space. And for everything there is a fee. Have you money?”

“A little. A purse hidden beneath my skirt.”

“Keep it for now, but if I send to you for it, do not hesitate to give it to the guard who brings the message. I have all but exhausted what I had. First I had to pay to be unshackled, then to have all this brought to me.” His gesture encompassed everything in his cell.

I was appalled by the notion that had he not had a few coins with him at the time of his arrest, he’d have been chained to the wall. Now that I looked, I could see the bolts that secured unfortunates there. Then I glanced again at the table.

“I see that you paid for pen and ink, as well.”

“Those are not luxuries, but rather a necessity, if you would have me emerge from prison a sane man.”

I picked up one of the sheets of paper and read the poem he had been composing.

When I look back and in myself behold

the wandering ways that youth could not descry

and see the fearful course that youth did hold

and met in mind each step I strayed awry

my knees I bow and from my heart I call

O Lord forget youth’s faults and follies all.

“Faults and follies,” I murmured. Choosing the wrong cause to follow? Or the wrong woman to wed?

“The princess’s women tell me you have written several poems in praise of the ladies who serve Her Grace. The few who were allowed to come with her to the Tower are most impressed by your skill with words.”

“Which gentlewomen are here?”

When I told him their names, his relief was palpable.

“Who is she, Jack?”

“I do not understand you.”

“You understand very well. I am told that one of the princess’s maids of honor inspired you to write more than one poem in her honor.”

“A poet must have a muse,” he protested.

I nodded encouragement, even though my heart was breaking. “Tell me about her.”

“Her name is Isabella. Isabella Markham. She was in attendance on the princess not long ago. Do you know where she is now?”

“The queen sent her sister’s maids of honor and waiting gentlewomen back to their families.”

He must have heard the anguish in my voice, or seen something in my expression. He seized me by the shoulders and waited until I met his eyes. “Audrey, Isabella is not my mistress. Only my muse. She is the lady on a pedestal, in the old tradition of courtly love.”

But he loved her, as he had never loved me. I’d always known that Jack had married me for what I could bring him. I could not fault him for that. Marriages are rarely made for love. And to give Jack credit, he had never claimed to be passionately in love with me.

He did love our daughter. I had no doubt of that.

And he was my husband, and would be until death parted us.

That being the case, I meant to do everything in my power to free him from the Tower . . . so long as it did not also endanger the princess.

Although I had served Elizabeth for only a short time, I had long been aware of the connection between us. That our appearance was so similar was only part of that bond. She had inherited King Henry’s presence, and his ability to inspire loyalty. Not even the continual backbiting of her other attendants could turn me against Her Grace.

Sir Thomas Wyatt was loyal to his princess, too. He went to his death on the eleventh day of April, marched out of the Tower and up Tower Hill. On the scaffold, he proclaimed her innocence, denying as he had all along that Elizabeth had been complicit in his treason.

A priest came to her chambers afterward, the one sent by the queen to witness Wyatt’s execution. He tried to shock the princess into betraying herself.

“He met a traitor’s death, madam—beheaded first. Then his body was quartered on the scaffold. His bowels and private parts were burned and the head and quarters went into a basket to be taken by cart to Newgate Prison. There they will be parboiled before being nailed up as a warning to all who would betray the queen. The head will go on top of the gibbet at St. James’s Palace.”

His graphic description sickened me, but if it affected the Lady Elizabeth, she did not let her revulsion show. Disappointed, the priest left. The councilors who came the next day likewise failed in their attempt to persuade Her Grace to admit she’d supported the rebellion. The only time I ever saw my princess show any reaction at all was when, in early May, she heard that she was to be placed in the care of Sir Henry Bedingfield.

“Is the Lady Jane’s scaffold still standing?” she asked in a shaken voice.

47

Tower of London, May 19, 1554

Two months after she’d been brought to the Tower by water, Elizabeth Tudor left it the same way. We traveled on a row barge accompanied by smaller craft carrying armed guards. Crowds gathered to watch from the shore and cheer for the princess, thinking she’d been freed. As we passed the Steelyard, where the merchants of the Hanse have their depot, guns fired a salute.

My longing gaze picked out familiar sights along the way. I could not see my old home on Watling Street from the river but St. Paul’s sat on a hill and dominated the skyline. We passed Seymour Place, the property of a new owner. And Durham House, where I had met the Earl of Surrey, the Duchess of Richmond, and Mary Shelton so long ago. Whitehall sprawled on one side of the Thames and Norfolk House stood on the other. I did not know who now lived in the latter. Queen Mary had taken it away from Queen Kathryn’s brother when he backed the attempt to put Lady Jane Grey on the throne in her place. Only days after being pardoned for that treason, he’d been arrested again for complicity with Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger.

As far as I knew, he was still a prisoner in the Tower.

So was Jack.

We disembarked at Richmond Palace, more than a dozen miles upstream from London. Sir Henry Bedingfield and his men surrounded the princess the moment she set foot onshore and allowed no one to come near her. She was escorted directly to the chamber where she would spend the night. Contrary to the rumors in the city, Elizabeth had not been set free. She was on her way to Woodstock, there to be held under heavy guard at the queen’s pleasure.

When I started to follow the princess and her guards into the palace, a hand caught my arm. “Not you, Mistress Harington.”

I did not know the man who’d stopped me, but he wore Queen Mary’s livery.

“I must go with—”

“Your services are no longer needed.”

My “services” had been of little help to Queen Mary. I had duly reported on the Lady Elizabeth’s activities. Her Grace read, she embroidered, she played cards with her ladies, she ate, and she slept. She walked for exercise as often as it was permitted. Sometimes other prisoners in the Tower called out to her, but I did not repeat those words of encouragement.

I did not object to being dismissed. I was not cut out to be a spy. But I did mind being left in limbo. “What about my husband?”

“I know nothing of him.” The fellow released me and turned away.

“Wait! How am I to reach Kelston?”

Somersetshire was a considerable distance from Richmond and I had no servants and little ready money. I had sent those who’d escorted me to Whitehall home when the queen ordered me to join the Lady Elizabeth’s household.

“That is not my concern,” the queen’s man said, and he kept walking.

At first I despaired. I stood on the river stairs, buffeted by a light wind and spray from the Thames, and could not think what to do. I was not accustomed to being completely on my own, but neither was I helpless. I squared my shoulders and counted my money. The only sensible thing to do was book passage on the next tilt boat bound for London.

During the journey, I had to endure bold stares from the men on board. They saw a woman traveling without a maid or a gentleman escort and thought the worst. Ignoring them as best I could, I set my mind to thinking what my next step would be. Those to whom I once would have turned first for help—Mother Anne and my sister Muriel and Sir Anthony Denny—were no longer alive. I dismissed at once the idea of asking assistance from Bridget and Master Scutt. My faithful Edith was still in Somersetshire, for I’d trusted no one else to look after Hester in my absence.

That left only my sister Elizabeth. From her husband I obtained an escort to take me safely to our house in Stepney. We’d left a few loyal retainers there. Within a week, I was back at Kelston and reunited with my precious daughter.

The strain was terrible during the months that followed. I did not sleep through a single night in all that time. I had no way of knowing what the queen would decide to do with Princess Elizabeth or with Jack. If my husband was charged with treason, all he owned, including everything I had brought to our marriage, would be forfeited to the Crown. Hester and I would be destitute.

Another fear haunted me, too. The queen, for all she wanted to believe that the Lady Elizabeth was not her sister at all, could not deceive herself forever. Elizabeth’s resemblance to King Henry—a resemblance I shared—was too pronounced. If Elizabeth was a threat to the throne, then so was I. In Mary’s mind, we were both the king’s bastards.

In January, Jack came home to us. He had spent more than eleven months a prisoner, a shorter incarceration than the last time, but not by much. It had been more than eight months since I’d seen him last. He was thinner, and more somber. He swore to me that he was a changed man.

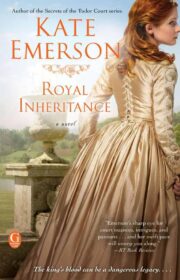

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.