We were rowed rapidly downstream. Since the tide was low, we could pass beneath London Bridge without danger of being dashed to bits, but once on the other side, I had an unobstructed view of what was about to become my prison, too.

Small clouds of kites and other carrion birds flew up in front of the barge, an evil omen. But at least, given the state of the tide, we were unable to enter by water through the Traitors’ Gate. I counted it as a small blessing when we landed at Tower Wharf instead. We walked into the massive fortress by means of a drawbridge.

Sir John Gage, Constable of the Tower, came forward to escort the Lady Elizabeth to her lodgings. She maintained a stoic fortitude until she saw that there were armed guards standing all along the way she must pass.

“What? Are all these harnessed men here just for me?”

“No, madam,” Gage assured her. “They are present at all times.”

“They are not needed for me,” she said with an attempt at irony. “I am, alas, but a weak woman.”

Some of the guards doffed their caps as she passed by. One knelt and cried out, “God save Your Grace!”

The way was narrow in places, and there were more drawbridges. We were in the middle of one of them when a terrible sound rent the air. It was so loud and so unexpected that it made me jump. One of the other ladies turned pale and another let out a squeal.

“You have nothing to fear,” Sir John assured us. “That is just one of the lions in the royal menagerie.”

I remembered Jack telling me that there were four of them and two leopards. Kept behind wooden railings, he’d said. Poor things. They were prisoners, too.

The Lady Elizabeth faltered only once, when she passed beneath the Bloody Tower and caught a glimpse of the scaffold erected at the far side of the court. It was the one where her cousin—my cousin—Lady Jane Grey had so recently been executed. No doubt it stood in the same spot as the earlier scaffold Anne Boleyn had mounted to meet the headsman specially imported from France to sever her neck with a sharp, merciful sword instead of an ax.

Sir John hurried us along past the grisly sight and through Coldharbor Gate, the main entrance to the inner ward. He led us not to some dank dungeon, or even to a single cell, but into the royal apartments—the same ones where Anne Boleyn had lodged before her coronation and again when she awaited execution.

There were four chambers—a presence chamber, a dining chamber, a bedchamber with a privy, and a gallery. The latter adjoined—although that door was now locked—the king’s apartments. Beyond there was also a bridge across another moat that led in turn to a privy garden. The whole was comfortably furnished and the Lady Elizabeth would be attended by a full dozen servants, but it was still a prison. The door through which we entered had two great locks in it. Sir John kept the heavy keys that fit them.

“Your hall and kitchen staff will be accommodated on the other side of the Coldharbor Gate,” he told the princess. “Your meals will be brought to you here.”

“And for exercise?” the Lady Elizabeth asked. “Are there leads upon which I may take the air? Am I to be permitted to venture into the garden?”

“For the present, my lady, you must remain within.” He backed hastily out of her presence. The sound of the keys turning in the locks sounded as loud as cannon fire.

In silence, my half sister explored her prison. The bedchamber was large and well appointed. A fire warmed it and tapestries had been hung on every wall to keep out the drafts.

“Leave us,” she instructed the few women she’d been allowed to keep. “All except Mistress Harington.”

When we were alone, I flung myself to my knees in front of her. “I am not here by my will, Your Grace. The queen gave me no choice.”

Elizabeth’s dark eyes, so like my own, bored into me for a long moment. Then she gestured for me to rise. “What threat does she hold over your head?”

“It is my husband, Your Grace. You know him well, I think. He is here in the Tower, on suspicion of complicity with the rebels.”

“Was he complicit?”

“I . . . I do not know. I do not think so. It seems to be the fact that he is known to have delivered a letter to Your Grace that brought him to the queen’s attention.”

A rueful smile played about her lips. “Ah, yes. But the queen can prove nothing, can she? There is no evidence of wrongdoing.”

Sir Thomas Wyatt might still be tortured into implicating others, but I kept that thought to myself.

“You have been instructed, I presume, to spy upon me.”

“Yes, Your Grace.”

“And will you tell the queen everything you hear and observe?”

“No, Your Grace, although I must tell her something.”

She nodded, accepting that. “I will be careful to say nothing incriminating in your presence.” And then she laughed. “If you are to pretend to serve me, you may begin at once. Fetch my other ladies. Then you must unpack the few belongings I was permitted to bring with me. At least I am allowed my books and paper and ink.”

I wondered if she meant to write poetry, as Jack had during his last imprisonment.

Elizabeth Sandes, one of the Lady Elizabeth’s most faithful servants, sent me a hate-filled look as she swept past me. “Lady Harington,” she sneered. “We know all about you.”

I could not fathom what she meant, but I accepted that my presence was resented. The princess might trust me, but even she would not befriend me when anyone could see us. I was resigned to being shunned. I told myself there would be compensations. In the end, Jack would be freed. The queen had promised it. And in the interim, I would be permitted conjugal visits.

In the days preceding the first of these, Mistress Sandes took to falling abruptly silent whenever I passed by, as if she had been talking about me. When she tired of that, she made a point of asking if my husband had ever written a poem in my honor.

He had not, but I lied and said he had.

“Master Harington penned poetic tributes to six of the princess’s maids of honor when we were last at Hatfield.”

“He is inspired by many things, Mistress Sandes.”

“One of those pretty young women had the honor of receiving two poems written to praise her beauty and her virtues . . . and perhaps more.” Her smirk left unclear whether she meant more poems or just . . . more.

“How lovely for her,” I said, and walked away. Either interpretation meant that Jack had favored another woman over me. That was a bitter pill to swallow.

The very next day, I found a scrap of paper among my possessions. On it was written a poem. The verses shook me to my core, for I could not help but read the worst possible interpretation into them.

Oh! most unhappy state,

What man may keep such course,

To love that he should hate

Or else to do much worse:

These be rewards for such

As live and love too much.

It was Jack’s work, to be sure, and enigmatic in many ways, but I took his words to mean that he had never loved me—that he was close, indeed, to hating me. And that now he loved another. The mysterious maid of honor at Hatfield, I presumed.

On Easter Sunday, after the mass celebrated in the Lady Elizabeth’s rooms by a priest the queen had sent, I was taken to see my husband.

Jack was lodged in far less sumptuous quarters in the Broad Arrow Tower, a squat structure two stories high that could only be entered by way of a staircase in the north turret. His cell was not as bad as it might have been. He had a pallet and bedding, candles, a brazier and coals to burn in it, a table, and a chair. And he had books and papers and pen and ink, which I suspected were more important to him than food or drink.

“Audrey?”

Under other circumstances, the astonishment in Jack’s voice would have been insulting. Clearly, no one had warned him to expect a visit from me. Nor, it seemed, did he know that I, too, now resided in the Tower of London. I lost no time apprising him of the situation.

“Queen Mary trusts you? Are you certain?”

“They both do, I think. The queen expects me to do what I must to free you. The princess accepts my word because she trusts you and knows I would never betray her.”

“Truly, I do not deserve you,” Jack murmured.

“What I deserve,” I told him, “is the truth. I could not answer the queen’s questions because I did not know what you had been up to at Ashridge and elsewhere, but I assured Her Grace that you are innocent. Are you, Jack?”

“I did nothing more than take a letter to Ashridge from the Duke of Suffolk in which he advised the princess to leave there for the greater safety of Donnington Castle. She’d already been given the same advice by others who had some inkling of what was afoot. She may even have been considering following it, but the queen’s ministers learned of the rebels’ plans before she could do so.”

“Her Grace was questioned about Donnington in my hearing,” I told him. “Members of the Privy Council came to the Tower to interrogate her. At first she said she could not remember owning a house by that name. Then she recalled the property but pointed out that she had never visited it. Finally, she agreed that there might have been talk among her officers of going there but she turned the tables on the councilors by asking why they should question her right to travel to any of her own houses at any time.”

“How did they react to being challenged?”

“One or two looked skeptical, but others were won over. The Earl of Arundel, upon leaving, threw himself to his knees and begged Her Grace’s forgiveness for having troubled her.”

“Is Her Grace well? In good spirits?”

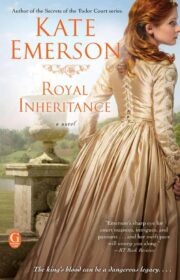

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.