A few minutes of conversation made it clear that Master Scutt knew nothing of Sir Richard’s latest threat.

“Once probate is complete,” Jack reminded him, “Audrey will be in a position to reward you for your services as Malte’s executor, and your own wife will be able to claim her inheritance.”

Scutt sent a fulminating glare Bridget’s way, making me think she had been the one responsible for the delay. She smiled sweetly back at him.

“I’ll see to it,” Scutt promised.

I hid my elation, lest Bridget turn against me again. If Scutt kept his word, there would be no more claims that I was King Henry’s daughter. Once John Malte’s will was properly entered into the official record, I would have documentary evidence to the contrary.

We went next to Mother Anne to announce our marriage, then visited my other sisters and their husbands. By the time we left London for Kelston, the largest part of my inheritance, I was at peace with all my kin.

We planned to live quietly in Somersetshire. Kelston was an idyllic setting for newly wed couple. Edith was with us, and little Pocket. Although the house had not been lived in for some time, it had been in the care of an industrious housekeeper. We settled in to wait for all the legalities to be settled.

The first good news to arrive was word that the will had been probated, thus rendering Sir Richard Southwell’s latest threat impotent. When he learned how he’d been thwarted, his first reaction would be anger and a desire for revenge. We resolved to rusticate awhile longer, giving his temper time to cool.

In July, news of the queen dowager’s remarriage became public. The Lord Protector was furious with his brother the Lord Admiral. Fortunately for the Lord Admiral, he had already succeeded in obtaining the young king’s enthusiastic approval.

“They are safe,” Jack reported, looking up from the letter that brought us this news.

“Thank the good Lord. They deserve their happiness.”

“As do we.”

I smiled at him. The weeks just past had been the most blissful of my entire life. Having established beyond a doubt that I was Audrey Malte, I was now quite content to be, only and forever, Audrey Harington.

44

Catherine’s Court, November 1556

The fire in the withdrawing room had burned down to ashes by the time Audrey stopped speaking, but she did not call for a servant to build it up again. It would do no good. She felt the cold deep inside herself where no flame could warm it. It was as she had feared. It hurt almost as much to relive moments of great happiness as it did to remember those filled with grief.

Hester stood and stretched. “I wish we could acknowledge being kin to the queen, but I am glad you and Father were able to wed.” She grinned. “I should not be here if you had not.” She headed for the door.

“Where are you going?”

At the sharpness of Audrey’s question, Hester turned in surprise. “To the hall. I want to look at the portraits.”

They lined the walls—Audrey and Jack, King Henry, King Edward, Queen Mary. There were even small ones of the Lord Admiral and the queen dowager, a gift on the occasion of Audrey’s wedding to Jack.

With an effort, Audrey hoisted herself out of the chair and followed her daughter. There was more she needed to tell her, and perhaps seeing the likenesses of those she’d talked about would enhance her words.

Hester stopped first in front of the picture of Queen Kathryn. “I know what happened to her. She died in childbirth.”

In her innocence of such matters, she said the words easily. She had no idea how many good women perished just as they achieved their greatest triumph. Audrey herself had almost succumbed. After Hester was born, the midwife had told her she was unlikely ever to conceive another child.

Audrey indicated the likeness of Thomas Seymour, Lord Admiral of England. “It was not long after his wife’s death that Seymour attempted to break into the bedchamber of his nephew the king. He killed one of the king’s dogs, lest it sound an alarm.”

This elicited a horrified gasp from Hester, who was as fond of dogs as she was of horses. Audrey, too, had been appalled by the Lord Admiral’s act, the more so because, at the time, she had just lost, to old age and infirmity, her own longtime companion. She’d buried Pocket in her garden just a few days before news of the Lord Admiral’s arrest arrived at Kelston.

“You were not yet a year old when he was executed for treason by his own brother, the Lord Protector. As I told you, your father was in the Lord Admiral’s service. He delivered messages for him and therefore was privy to many of the Lord Admiral’s plans.”

The worried look in Hester’s eyes told Audrey that her daughter had an inkling what she would hear next.

“Jack was arrested, too. He was in prison for over a year.”

“But he was released. It all ended well.” Hester moved on to the portrait of King Edward and frowned.

“The young king reigned only a few years,” Audrey said. “Upon his death, the country was very nearly plunged into civil war. That was averted, but more plots against the new queen, Mary, were quick to surface.”

“I remember,” Hester said. “I was old enough by then to know something of what was happening. You and father were both taken away. Did Father conspire against Queen Mary?”

“Never! No more than he knew of the Lord Admiral’s plans to kidnap King Edward. But innocence does not guarantee safety. You will remember that I spoke of Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger?”

Hester nodded.

“He attempted to march into London and capture Queen Mary to prevent Her Grace from marrying Philip of Spain. People were in great fear of Spanish rule in those days.”

And of the return of Catholicism to the land, Audrey added to herself. That fear had been well founded. They were all good Catholics now, under the rule of Mary and Philip, no matter what they believed in their hearts.

“The Duke of Suffolk was to raise the Midlands,” she continued. “That was the Marquess of Dorset, Lady Jane Grey’s father. He’d been elevated in the peerage two years earlier, when his wife’s brothers died. Poor Lady Jane was already in the Tower of London, for she’d been a pawn in an earlier scheme to keep Mary Tudor from claiming the throne. At the time of Wyatt’s uprising, your father was at Cheshunt. He had just delivered a letter to Princess Elizabeth at Ashridge when two of the duke’s brothers, on their way to join Suffolk, stopped there for the night. They tried to convince Jack to join with them. He refused, but the mere fact that they’d spent the evening together was sufficient to condemn your father in the queen’s eyes.”

“Did Wyatt mean to put Elizabeth on the throne in Mary’s place?”

“Some say he did. No one really knows.”

From what Audrey had heard since, the leaders of the rebellion had been a confused lot with conflicting goals and little in the way of organization. Any well-trained housewife could have mounted a better campaign.

“It scarce matters what his goal was,” she continued. “Queen Mary was suspicious of her half sister and that suspicion extended to everyone associated with her, including your father. He was accused of being a conspirator and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Then the queen ordered Elizabeth to come to London and lodged her, under guard, in a secure corner of Whitehall Palace near the privy garden.”

Hester listened attentively, her eyes wide. Audrey prayed for the strength to make her understand what the rest of her story meant. Hester had not asked again to go to court and meet her royal aunt, but that did not mean she had given up her ambition to be a maid of honor. In telling her daughter the next part of the story, Audrey hoped to dissuade her, once and for all, from ever trying to trade on her royal inheritance.

She drew in a strengthening breath. She needed her wits about her now more than ever. When she’d begun, her only goal had been to make certain that her daughter did not grow to adulthood in ignorance of her heritage. Audrey would not have wished that fate on anyone. But now there was more she must do. The simple truth was out but it was not enough. Now she must shape her remaining memories into a cautionary tale, to prevent Hester from misusing her newfound knowledge.

45

Whitehall, March 1554

When word came that Jack was back in the Tower, I at once made plans to leave Somerset for Stepney. We’d acquired our house there some three years earlier. Even though he’d just spent many months imprisoned for no greater crime than being one of the Lord Admiral’s loyal retainers, he’d laughed when he first noticed that we had such an excellent view of his former prison. Then he’d recited the epigram he’d written on the subject of treason:

Treason doth never prosper. What’s the reason?

Why if it prosper, none dare call it treason.

That was how he passed his time while incarcerated for the first time—writing. He translated Cicero’s The Book of Friendship and composed verses, including a sonnet to the Lord Admiral that, had anyone seen it, would most likely have added to the length of Jack’s imprisonment. The poem ended with a couplet:

Yet against nature, reason, and laws

His blood was spilt, guiltless without just cause.

I did not like to think what new verses my husband might be composing. He was temperate in speech, but he seemed to believe that expressing his thoughts as poetry gave him license to say what he would. The day after my arrival in Stepney, I applied to visit him. When that request was denied by the constable of the Tower, I presented myself at court and begged an audience with Queen Mary.

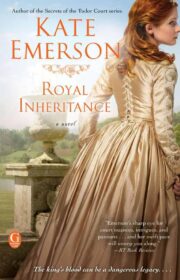

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.