Sir Richard followed at a leisurely pace and watched in stone-faced silence as we got Father into bed. Mother Anne sent a servant for a posset. Only after she’d coaxed Father into swallowing a few sips of the healing brew did Southwell speak in a low, menacing rumble of sound.

“This is not finished, Malte. The king’s death has changed nothing. In truth, I have even more influence in this new reign. You might think on that while you recover.”

Having uttered that vague but very real threat, he turned on his heel and left the house. Young Richard rushed out after him.

The slam of the door in the shop below us made Mother Anne jump it was so loud. I winced. Father’s eyes flew open and he reached for my hand.

“I want you to be safe after I am gone, Audrey.” His pleading gaze broke my heart, as did the lack of strength in his grip. His fingers slid away from mine, too weak to hold on. “Southwell looks after his own.”

“And when I am no longer useful to him? I’ll not be safe then.” I thought of the Earl of Surrey and a shudder ran through me.

“You must marry someone, child,” Mother Anne put in. “And that boy is not his father. There is kindness in him. Wed him, bed him, bear a child or two, and your life will be your own again.”

“No, it will not. Once I have a husband, he will own everything, even the clothes on my back. A wife is no better than a slave. The only hope I have of happiness is to marry a man who truly cares for me. You have had that happiness with Father. How can you ask me to accept anything less?”

“You still want Jack Harington,” Father whispered, “but the man has no estate and no fortune of his own. He is a good man, Audrey, but he cannot provide for you or protect you.”

“Nor have you seen him for some time,” Mother Anne put in. “He has accepted that his pursuit of you is futile. You must do the same.”

I nearly blurted out that I had seen Jack, and not so very long ago, either. Only two months had passed since our journey to Windsor Castle. I caught myself in time. It would only distress Father to learn of that trip, and to know that I had sought Jack out at Seymour Place. I let him continue in his belief that it had been years since we’d last met.

“Whatever man marries me would have the wherewithal to protect me. He’d have control of my inheritance.”

“You will never be able to tell, Audrey, if such a man loves you for yourself or only wishes to wed you for the land you will inherit when I die.”

Fighting tears, I dropped my gaze to my hands. They were clenched so hard that the knuckles showed white. I could say no more without causing Father greater distress, but that was not the only reason I wanted to weep.

I loved Jack Harington, but he had never once said that he loved me, only that he would wed me if he could. It did little to soothe my troubled thoughts to remember that he had behaved nobly, refusing to ask for my hand for exactly the same reasons Father gave—his poverty and lack of prospects.

And what of the other, I wondered—my royal inheritance? That strain of Tudor blood, tainted though it was, had value only if it was acknowledged by the king and now His Grace was gone without ever revealing my true identity to the world.

I frowned in confusion. If there could never be any proof of my parentage, then why was Sir Richard Southwell still so intent upon my marriage to his son?

“My lands will make me a considerable heiress,” I said aloud, “but there are other heiresses far more wealthy than I am. Why has Sir Richard not pursued one of them for his son?”

“He wants you.” Father’s whisper was weak but still audible.

“Why?”

“What does it matter? He will not give up. The more you resist, the more determined he will become to have his way.”

Was it that simple? A craving for power over others? I swallowed convulsively, remembering that Sir Richard Southwell had brought down one of the most powerful families in England. The Duke of Norfolk was still a prisoner in the Tower and under sentence of death.

As if she read my thoughts, Mother Anne said, “Sir Richard will leave us in peace once you agree to marry the boy.”

Abruptly, I stood. “I must be alone. To think.”

Responsibility weighed heavily upon me. I did not believe that Father had long to live. Once he was gone, who would protect those he left behind? Mother Anne and the servants and the apprentices would be almost as vulnerable as I was. My actions could bring disaster down upon us all.

I fled the sickroom and the house, pausing only long enough to don my warm cloak. I dashed into Watling Street, catching Edith off guard. By the time she gathered her wits and tried to follow me, I was already out of sight.

Desperate to get away from everyone, I had no destination in mind as my running steps slowed gradually to a fast walk. Oblivious to my surroundings, deaf to the noise and confusion all around me, I pushed my way through the throngs of people clogging London’s streets. I paid them no heed, but I tried in vain to ignore my own chaotic thoughts.

40

At length, when I stopped and looked around, I realized that my feet had carried me into East Cheap and then north along Bishopsgate Street. The former priory of St. Helen’s was within sight.

The servant who answered the door of Sir Jerome Shelton’s house radiated suspicion. I suppose that was only natural, given the events of December and January. Deciding that he would not be likely to tell me if Lady Heveningham was staying there, even if she was within, I contented myself with asking if he would deliver a message to her. With obvious reluctance, he agreed. I gave him my name and asked that she be told I wished to speak with her. Then I left.

I had walked no farther than the Merchant Taylors’ Hall before another servant came running to fetch me back. Mary Heveningham welcomed me with open arms.

We cried together over the fate of the Earl of Surrey.

After she roundly cursed Sir Richard Southwell for his part in the downfall of the Howards, I admitted that Sir Richard was the reason I had sought her out. My story did not take long to tell. She had guessed most of it already.

“Do you want to claim royal blood as your inheritance?” she asked me in her familiar blunt fashion.

“No!”

“That is wise. But consider that it is also true that your dowry is sufficient to make Sir Richard determined upon the match. And for a certainty, that wretched man does not like to be thwarted.”

“Let him find some other heiress!”

“Young Richard is baseborn, Audrey. That counts against him with some girls’ fathers.”

“But a bastard is good enough for a bastard? Is that it?” I let my bitterness show.

“Still,” Mary said thoughtfully, “there may be some advantage to continued resistance. I have not done so badly refusing to be rushed into marriage.”

“But Tom Clere died,” I objected.

For a moment, her eyes swam with unshed tears. She hastily brushed them away. “He did. And I will grieve all my life for him. But I have a good husband and a fine healthy daughter and am about to return to them. I only came to London to fulfill a promise to the duchess.”

I was suddenly ashamed. I had not even thought to ask after the Duchess of Richmond. “Where is Her Grace?”

“At Reigate in Surrey, not so very far away. She has been granted the care of her brother’s daughters.”

“And their governess?”

“Your Edith’s mother? Yes. She is with them. They’re safe enough, and have sufficient funds to live upon, although all of the duchess’s possessions were confiscated by the Crown at the same time they took everything that belonged to her father and brother. She was fortunate the king allowed her to keep the clothes on her back.”

“Will they execute the duke?”

Mary shook her head. “I wish I knew. That is why I came here—to present a petition to the new Privy Council to spare Norfolk’s life. The Lord Protector granted me a few minutes of his time, but he was not encouraging. I very much fear that, at the least, the duke will remain a prisoner so long as young Edward is king.”

“I pray the king will spare the Duchess of Richmond’s father,” I murmured, acutely aware that it had been my own father, who even now still lay in state in Westminster, who had imprisoned Norfolk and wanted him dead.

“And I will pray that God spare yours.” At my startled look, Mary said, not unkindly, “John Malte, Audrey. Perhaps he is not as ill as you think. Has a physician been called in?”

“He will not have one. He consulted a doctor the last time he was seriously ill and the treatments the fellow prescribed were so distasteful, and so ineffectual, that he lost all faith in medical men.”

“A healer then? Some wise woman skilled in the use of herbs?”

But I shook my head. “He’ll take possets from Mother Anne—his wife—but naught else. And those do little but ease his pain. I fear he is dying, Mary. He grows weaker every day. I . . . I think he has lost the will to live, especially after word reached him of the king’s death.” As Mary had, I swiped at my tears before they could fall. Fishing a handkerchief out of my pocket, I blew my nose.

“I am saddened by your grief, my friend, and you will not like me much for saying this, but it will serve you best if John Malte does not recover.”

At first I did not think I could have heard her correctly, but she repeated this outrageous statement, adding, “You know already that one of the few rights a girl has is to refuse a marriage that is distasteful to her. There is another part of the law you may not have heard. I suspect that men keep silent about it for their own advantage. It is this: a girl who is fourteen or older and not yet betrothed to anyone at the time of her father’s death can inherit in her own right. So long as she remains unmarried, she keeps control of her property and her person. You must not, no matter how great your desire to ease John Malte’s mind, allow him to extract a deathbed promise from you. Stand fast, my friend, and you will soon be free.”

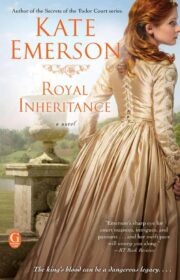

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.