Hester frowned at this. “I remember that you said your father—John Malte—kept warning you against wandering off by yourself. And that he hired a neighbor to go with you to court, before the king sent Edith to you.”

“Even the plainest girl will have the men flocking after her if she is on her own.” Audrey smiled a little. “That day, leaving Windsor, Edith’s revelations made Jack uncomfortable. He mumbled something about how few women there were at court. Even among the servants, men outnumber women a hundred to one. But he had to admit that perhaps Edith had the right of it. And in the end, I agreed that Joanna might be more to be pitied than reviled. I realized that John Malte must feel the same. Why else would he leave her a bequest in his will? But I still had my doubts about her truthfulness. I suspected her of lying about my paternity.”

Hester lifted her head from Audrey’s knee. “There must have been a way to learn more. Surely someone among the king’s men, someone who was at court before you were born, knew the truth.”

“That occurred to me, too, and I said so to your father. My determination to go on asking questions worried him a great deal. He warned me that I must not pursue my inquiries openly, not when they concerned the king. That, I told him, left me with only the king himself to ask.”

“What did Father say to that?”

“That if His Grace had meant to claim me, he’d have done so long ago. I’d once thought the same, but now I was of a different opinion. My memory had been jostled. I found myself recalling more about the day His Grace rescued me. It was the same day upon which Anne Boleyn was created a marquess in her own right. By the time King Henry learned of my existence, he was deeply committed to marrying her. To acknowledge me then would have angered her, and Queen Anne was legendary for her temper. I think perhaps King Henry was a little afraid of her.”

“Did you convince Father of your reasoning?”

“I chose not to debate the matter with him. Besides, by then I had begun to realize that something else was bothering him. I’d sensed it throughout our journey to Windsor. I knew that furrow in his brow.”

Hester grinned. She was familiar with it, too, and with what its appearance betokened.

“When I tore myself away from my obsession with finding out who’d fathered me and considered Jack’s behavior, I realized that he’d been relieved to leave London behind for a few days. But most curiously, now that we were on our way back, he was passing anxious for the journey to end. It was as if he knew something of importance had happened while we were gone.”

Within moments of returning to the house in Watling Street, her suspicions had been confirmed. Bridget had already been by to report the latest news from court, relayed to her by Master Scutt.

“Father was on the verge of going to Sir Jerome Shelton’s house himself to fetch me home,” she told Hester. “The first words out of his mouth when I walked in were: ‘Has Lady Heveningham been questioned?’ My blank stare must have told him I had no notion what had happened. He looked relieved, but then he ordered me to stay away from Mary, and from anyone else I had ever met through the Duchess of Richmond and her brother . . . with one exception.”

“Why was he so upset?” Hester asked.

“While I was at Windsor, the Earl of Surrey had been arrested on suspicion of treason. Sir Richard Southwell had laid evidence against him before the Privy Council.”

36

December 12, 1546

That Sunday, I went with Edith and Bridget to watch the Earl of Surrey be led through London on his way to the Tower. I vow, every citizen, every apprentice, and every stranger in London turned out to witness his disgrace.

Jostled by the crowd, I soon became separated from the others. I kept one hand on the purse I’d acquired to replace the one I’d given Joanna. The pickpockets were also out in force.

It was not idle curiosity that made me want a close look at the earl. I wished to make certain he was not accompanied by other prisoners, perhaps his sister, perhaps even Mary Heveningham. And, irrational though it was, given that Jack Harington had long since shifted his allegiance to the Seymours, I worried that he might be among them. I’d not heard a word from him since returning to London.

The earl’s name was on everyone’s lips, along with ever more creative accounts of his arrest. I had heard the true story, thanks to Master Scutt. Ten days earlier, even as I was making my way to Windsor Castle and back, Surrey had dined at Whitehall Palace. The captain of the king’s halberdiers, pretending he had a private matter to discuss with the earl—that he wanted Surrey to intercede with his father, the Duke of Norfolk—lured Surrey away from the crowded hall. Once the earl was separated from his own men, other halberdiers seized him and carried him away to the river stairs. A boat was waiting there to take him to Blackfriars landing and thence to Ely Place in Holborn and the Lord Chancellor, who informed him that he was to be held there, a prisoner, by the king’s command.

Now charged with treason, Surrey was being taken from Ely Place to the Tower. He had been stripped of all the trappings of his rank. All his possessions, even his bay jennet, had been seized by the Crown. Thus, even though he was nobly born, the son of a duke, he was being made to walk the mile-and-a-half distance—straight through London itself.

There was no fanfare as he approached the spot where I stood waiting. No silk banners waved. The only entourage accompanying him consisted of a contingent of burly guards.

I breathed a sigh of relief when I saw that he was the only prisoner. If anyone else had been arrested, they had at least been spared the indignity of public humiliation.

Surrey himself was almost unrecognizable. In plain garments undecorated with jewels, he stared straight ahead, his countenance stoic. Onlookers, who had been noisy and boisterous as he approached, fell silent in his wake. It was usual to pelt prisoners conveyed through the city in carts with rotten produce and stones. No one threw anything at the earl.

Here and there, men removed their caps as a mark of respect. Others looked away from the sight of the once-proud nobleman brought low. This was not a day to remember Surrey’s drunken rioting and window-breaking. Men instead recalled his role in the French war—his heroism and military prowess. Only the presence of the earl’s armed escort prevented them from attempting a rescue. As it was, some shouted out words of encouragement to the prisoner.

Beside me, an old woman began to wail. Others echoed the lamentation, until the entire city seemed to be in mourning for the Earl of Surrey. Suddenly nervous, the guards hustled their prisoner on his way. Around me, the cries died down, but they were taken up farther along the route. Inarticulate sounds close at hand were replaced by muttered words.

“He’s bound for the headsman’s ax,” one man said.

Public executions were a popular form of entertainment, but this fellow did not sound happy about the prospect.

It terrified me. In a panic, I broke free of the press of people and fought my way back through Cheapside. Surrey had been arrested before, but this time was different. This time the charge was treason and he was bound for the Tower, not the Fleet. I could not help but think of what had happened to two other prisoners in that terrible place—Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard. They had died there, condemned by the same king who had once loved them both. Was Surrey truly about to join his kinswomen in facing the headsman?

I was nearly home, just turning from West Cheap into Friday Street, when Edith and Bridget rejoined me.

“Did you hear?” Bridget’s eyes were bright with excitement. “The Duke of Norfolk arrived in London from Kenninghall this morning and now he is also under arrest. He’s being taken to the Tower by water even as his son is marched there.”

I felt as if a cold hand clenched around my heart. Thinking about Surrey’s fate had been bad enough, but this was infinitely worse. “And the rest of the Howards? What of them?” The Duchess of Richmond had been at Kenninghall with her father.

“Mayhap they’ll be made prisoners, too. The king has sent troops to seize all of the duke’s possessions. They belong to His Grace now, for traitors forfeit all they own.”

“The Countess of Surrey is at Kenninghall.” There was a tremor in Edith’s voice, reminding me that her mother would be there, too, in attendance on the countess’s children. “Lady Frances is expecting another child in February.”

I reached for Edith’s hand and squeezed it.

As is ever the case, no one knew exactly what the Privy Council heard from the many witnesses they deposed, but that did not stop the good citizens of London from speculating. Within hours of her arrival in Lambeth, word that the Duchess of Richmond had been summoned to testify against her brother had reached the marketplace. Rumors flew. She meant to have her revenge on Surrey for thwarting her marriage to Sir Thomas Seymour. She was bound for the Tower herself. She had tried to throw herself on the king’s mercy—he was her father-in-law, after all—and he had sent her away without an audience.

Edith received a more reliable report from her mother, who wrote from Norfolk to tell her that the Countess of Surrey had been allowed to leave Kenninghall for one of the duke’s smaller houses, although that one too now belonged to the king. Most cruelly, Lady Surrey’s children had been taken away from her. Surrey’s heir had been given into the keeping of Sir John Williams while the three girls and the younger boy had been placed with a loyal East Anglian landowner. Edith’s mother had been obliged to choose between her much-beloved Lady Frances and the young Howards. In the end, she’d remained with her youthful charges.

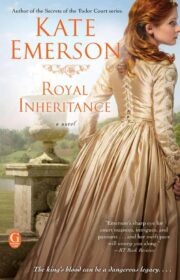

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.