Looking sulky, she picked at a chipped fingernail and refused to meet my eyes.

“I want to know what the king said to you that day.” That was not all I wanted to know, but it was a place to start.

“He was angry because Dobson struck you.” Suddenly defensive, she glowered at me. “A father has a right to deal with a child as he will.”

“Dobson was not my father.”

“He was your stepfather. It was not your place to defy him.”

“Nor the king’s?” I took a breath and blurted out the question I most needed to have answered. “Is he my father? Am I King Henry’s child?”

The change in her was immediate. Her irritation with me was replaced by a far stronger emotion, one there was no mistaking. It was fear I saw in her eyes before she averted her gaze.

It had not occurred to me before coming to Windsor that by telling me the truth my mother might place herself in danger. I had not anticipated the possibility that she might have been threatened to keep silent about my paternity. Or bribed. Or both. Did she fear that if she made such a claim about the king, even if she only confided in me and in private, she could be taken up for treason?

“I swear I will not repeat to anyone what you say to me.” I leaned forward to take her rough, work-worn hands in mine.

She looked past me at Edith and Jack. “Tell them to go away.”

“Leave. Please,” I said without glancing over my shoulder. I heard the faint rustle of Edith’s skirts and the shuffle of Jack’s boots as they honored my wishes. The door closed behind them with a thump.

My mother freed herself from my grip and crossed her arms over her bosom. Even in the dimly lit hovel I could tell that she was glaring at me. “You were never anything but trouble! I should have gone to the village wise woman and done away with you before you ever drew breath.”

It hurt me that she hated me so much, especially when it was far too late to change anything that had happened. I rebuilt the shield around my heart and plunged ahead. “Who was my father? What man did you lie with in the year before my birth?”

“I did couple with the king.” For a moment Joanna—it was easier to think of her by her Christian name than to regard her as my mother—allowed herself to look smug. The expression faded quickly. She had harbored too much resentment for too many years. “He was mad for Anne Boleyn in those days and she would not let him into her bed. I had something of her coloring in my dark hair and in my eyes. The king wanted to swive her but she held him off. So he bedded me. Called me Nan once or twice while he was at it. Men!”

“Then I am his child?”

I’d thought myself prepared for this moment, but I had not. If the king was my father, why had he never acknowledged me? Why had he given me away? Why had Father—John Malte—lied to me? That last was the most hurtful thought. The suspicion was not new, but it pained me that I might finally be obliged to accept the truth of it.

“You . . . might be,” Joanna said.

“You are in some doubt? How can that be?”

At the astonishment in my tone, she gave a bitter laugh. “How do you think? The king was not the only one who bedded me. I liked coupling in those days. I went with any man who asked me and a great many did. How do you think King Henry found me, eh? He followed one of his courtiers to my bed.”

“Did . . . did you lie with John Malte?”

“I may have. I hear he claimed you were his get.”

“He was well rewarded for doing so by the king.” This time it was bitterness that laced my words. “But surely, even with so many men, when you discovered that you were to have a child, you must have considered which one was most likely to have fathered me.”

“Oh, I had one or two likely prospects—the ones who had money.”

“And then I was born and you saw that I had bright red hair. That must have put an end to your doubts.”

“Ah, there’s the pity of it. The king was not the only redheaded man I let into my bed. There was another.”

“Who?”

“Let me see your money first.”

I reached through the purpose-cut placket in my skirt and into the purse suspended from my waist, feeling for the shape and weight of the angels. I extracted one. “The other when you answer me.”

“Even if you do not like the answer?”

With a sigh, I produced the second coin. I was prepared to pay even more if it would loosen her tongue.

“I do not remember his name. I am not certain I ever knew it. He was a toothsome fellow newcome to court and he was generous with his gifts. He was at Windsor, mayhap, to present a petition to the king. Then he was gone and I never saw him again. But he had a head of flaming red hair, not unlike your own.”

Her face gave nothing away. If she had invented this red-haired man out of whole cloth, I had no way to prove it. Fear of what the king might do to her if she named him as my father might have prompted her to lie, but it was equally possible that she had just told me the truth. If she had, I would never have an answer to the question of who had fathered me.

“If he was long gone before my birth, that still left King Henry,” I said slowly. “He knew nothing of my existence until he found me crying that day. Why did you not approach him when I was born? Why did he not know about me?”

“The king went away from Windsor, too. And how was I to make my way to him even when he came back again?” She spat. “I am a laundress. I’ve no business in the king’s lodgings. And once I was burdened with a squalling brat, no more courtiers came begging for my favors. I had to settle for Dobson.”

All my fault, I thought. Again.

“I regret that your life has been so hard.” I rose from the bench, resigned to the fact that I had learned all I would from her.

Unexpectedly, Joanna said, “Malte’s a good man. He looks in on me now and again. He even gave me money when Dobson left me and took all that I had saved.”

“But is he my real father? He does not have red hair.”

“Mayhap he had a red-haired grandmother.” She snorted a laugh.

I turned to leave. I was almost at the door of the hovel when she spoke again.

“You have far more already than most girls ever get. It would do you no harm to remember your poor old mother from time to time, or to share your good fortune.”

I was a fool to do so, but I detached my purse and handed it to her. Then I left her house without looking back. I did not even wait to make sure Jack and Edith were following me. I kept walking until I reached the waiting tilt boat.

35

Catherine’s Court, November 1556

Was the king your father or not?” Hester demanded.

“I was not yet certain.” They were within sight of the stable and the horses, scenting hay, perked up and moved faster.

“If he was, then Bridget Scutt is not my aunt at all.” Hester sounded delighted by that. “Instead I have two other aunts, and one of them is the queen. Will you take me to court, Mother? I would like to meet Aunt Mary.”

“Queen Mary,” Audrey corrected her, beginning to be alarmed. Hester was too young to realize that the queen might take exception to a claim of shared royal blood. “No more of this, Hester. I would not have us overheard.”

The girl had sense enough to obey, but Audrey could see she was bubbling over with excitement. Questions threatened to burst out of her at any moment, no matter who was within earshot.

Audrey dismounted too quickly and had to grasp Plodder’s mane to steady herself.

“Is aught wrong, mistress?”

She waved off the groom’s concern but reached for Hester’s hand. “Help me into the house, child. I find I am in need of rest after all that exertion.”

As soon as they reached Audrey’s bedchamber, Hester resumed begging to visit her newly discovered aunts. “If not to court, then let us go to Hatfield. Father has been there often. I am certain we would be welcome.”

Audrey was equally certain they would not. Moreover, she was suddenly beset by the conviction that it had been a terrible mistake to tell Hester anything at all about her heritage. The girl was too young to understand the danger.

She eased herself into the cushioned chair by the window and stared out at the landscape they’d just ridden through. She missed the London skyline already. How curious, she thought, since they’d be no safer in Stepney.

Hester flung herself down onto a pillow at her mother’s feet. “When, Mother? When can I meet them?”

“You do not even know for certain that those two royal ladies are your kin.” Audrey’s voice was sharper than she’d intended, making Hester wince. She moderated her tone. “Let me finish my tale, my darling girl. Then we will talk about where you can and cannot go and why.”

“But—”

“I understand your desire. Believe me, I do. But matters are never as simple as they seem. Will you allow me to tell you what happened next?”

A deep, sulky sigh answered her, but it was accompanied by a nod.

“On the way back to London, I shared with my companions what Joanna Dobson had told me. I was surprised when Edith remarked that Joanna was much to be pitied. She said that before she came to me, she had experienced for herself just how difficult it was to be young and female at the royal court. A noblewoman might not need to fear for her virtue, she said, and most gentlewomen were safe enough, but servants have no powerful relatives or position to protect them. They are considered fair game. Edith had felt safe only so long as she kept close to her mother, and her mother’s presence only served to ward off the danger because she was in service to Lady Frances, the daughter of one earl and wife to another.”

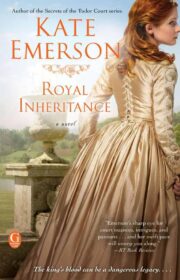

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.