He had not yet noticed me. Coward that I was, I considered creeping away before he did. Although our encounters had been few and far between, each one had left me with a bad taste in my mouth. I did not relish enduring another conversation with him.

I did not move quickly enough. The young man at his side turned his head my way. With a start, I saw that he was Richard Darcy, the boy Father intended me to marry. Darcy tugged on his father’s sleeve. A moment later, two coldly analytical stares pinned me where I stood.

“This way,” said a familiar voice behind me, and my heart began to race as fast as a cinquepace.

Jack Harington tugged on my arm, drawing me into the concealment of a very large yeoman of the guard. As swiftly as we could, given the crush of people, we fled toward the safety of the palace. I did not look back. If Southwell and his son were following us, I did not want to know it.

“Father’s workroom,” I hissed when we’d slipped through the nearest entrance. “No one will disturb us there.”

“Nor will we be private,” Jack whispered back.

When my steps faltered, he pulled me onward. He said no more but steered me away from the place where Father and two of his apprentices worked and into a deserted passageway. We paused by a window that overlooked the expanse of garden we’d just left. Sir Richard Southwell was still there. He had not pursued me.

Breathing a sigh of relief, I waited for Jack to speak. For the longest time, he did not. He simply stared at me, as if he were trying to memorize my appearance. All the while he looked deeply troubled.

Finally, I grew impatient. “What ails you, Jack?”

“I have begun to think I was wrong.” He reached out to finger a lock of my hair. It had come loose during our precipitous flight. With great care, he tucked it back into place. Everywhere he touched, I felt a line of fire.

“Wrong about what?” I spoke in a breathy whisper. Was he going to declare himself at last?

“About how beautiful you are.”

I frowned. I did not want praise. I wanted love. “I am eighteen years old and not yet betrothed,” I said bluntly.

“You soon will be. They will wear you down.”

I stepped back from him, a spurt of anger burning through my besotted state. “I cannot be forced to wed someone I do not like.”

“You can be coerced. As can I.”

“You are to marry?”

He must have heard the stunned surprise in my voice because a faint smile began to play around his lips. “No, Audrey. I mean that I have been warned to stay away from you.”

“By Sir Richard Southwell?”

“By Sir Thomas Seymour.”

I frowned. “But . . . Sir Richard is Surrey’s man, not Seymour’s.”

“Is he? There are forces at work at court that you know nothing about, Audrey. A struggle for power that will affect us all. You must have a care for yourself. Hold out too long, and there could be terrible consequences for all those you hold dear. For John Malte, mayhap. Or for your sisters.” He gave a short, bitter laugh. “And yes, mayhap for me. No one is safe from the king’s whim, not even the highest peer in the land.”

I blinked at him in confusion. The highest peer in the land was the Duke of Norfolk. Surely Jack did not mean to say that the duke was in danger. “Say what you mean in plain English, Jack.”

“If you anger Sir Richard sufficiently, he will turn vindictive, and he has King Henry’s ear. He has never hesitated to destroy those who stood in the way of something he wanted.”

“Perhaps I, too, have the king’s ear.”

Jack went very still. “Is it true, then?”

I looked away. So, he had wondered if I was a royal merry-begot. “I . . . I do not know. No one will tell me.”

We stood that way, unmoving, staring into each other’s eyes, until the sound of rapidly approaching footsteps broke the spell. A liveried page, scurrying past on some errand, barely spared us a glance, but his appearance was enough to remind us that to be seen together by anyone at this juncture would be most unwise.

“Know this,” Jack said before he left me. “If I were in a position to marry any woman I wished to, it would be you, Audrey.”

Then he was gone.

He hadn’t said he loved me.

Neither had he said that he did not.

Two days later, in Father’s company, I had my long-awaited audience with the king. There was no opportunity to speak with His Grace in private. He called us to him only to inform us that he intended to grant us, jointly, the lordship and manor of Kelston, the lordship and manor of Easton, the capital messuage of Catherine’s Court, and four hundred ewes. The properties were located in Somersetshire. They’d been monastic lands once, forfeited by the nunnery of Shaftesbury when it was dissolved. They were valued at slightly over thirteen hundred pounds.

“It is an exceeding generous gift,” I said to Father after we’d backed out of the presence chamber and returned to our lodgings.

“I am being pensioned off, Audrey,” Father said. “I am to leave my post at court before the end of the year.”

As a young child, I might have believed that was all there was to it, but I knew better now. The king’s largesse was too great. Royal retainers rarely received annuities amounting to more than one hundred pounds.

“How much of this grant is to be included in my dowry?” I asked.

“You will be a considerable heiress,” Father allowed.

“And so this is all part of the king’s plan to push me into marriage with Richard Darcy.”

“I do not understand why you are so opposed to the young man.” For once, Father let his annoyance show. “He has no flaws that I can see.”

“And if he turns out like his father? Unfaithful to me? Begetting bastards right and left? Murdering men in sanctuary?”

“Sir Richard Southwell has his faults, but he is not without good qualities. He has served the king long and well and continues to do so.”

Father’s words lacked conviction, but the stubborn tilt of his jaw warned me that there was no profit in further argument.

31

The next day, Richard Darcy sought me out, sent by his father. He seemed as reluctant as I was to spend any time together. We passed a quarter of an hour in stilted conversation, most of it concerning his studies at Cambridge and his desire to make something of himself when he entered one of the Inns of Court.

“Do you like music?” I asked him.

“I am not particularly musical. When I have time for amusements, I prefer to hunt. I am a good shot with a crossbow.”

“Have you ever written poetry?”

He looked at me as if I had gone mad. “Whatever for? It is difficult enough to copy out what others have written and I only do that when my tutors insist upon it.”

“Master Darcy,” I said. “I bear you no ill will, but I will never tie myself to you with the bonds of matrimony.”

“I do not much care for you, either,” he said.

“Oh. Well . . . that is good.”

His quick smile almost made me like him.

Father and I remained at court until the king left on a hunting progress on the fourth day of September. I did not see His Grace again, but I was thrust repeatedly into Richard Darcy’s company. Every time, as I had on that first occasion, I told him bluntly that I would never be his wife.

“You will, you know,” he said on the last day. “Father will not give up. He says you are too rare a catch.”

“I cannot think why. My father is naught but a simple merchant tailor.”

If I had not been watching for his reaction, I might have missed it. As it was, I saw the slight widening of his eyes and heard the quick, indrawn breath.

“That is not what your father thinks, is it?”

“I do not know what you mean.”

“You need to spend more time at court, Master Darcy. You would learn to be more convincing when you tell a lie.”

He looked over his shoulder toward the door of the workroom. We’d been left alone there except for Edith. She sat in a distant corner and appeared to be absorbed in her mending. I had no doubt but that she could overhear what we said to each other, but I did not care.

“Father believes you are the king’s child,” Darcy admitted.

Although the idea was scarcely new to me, this was the first time anyone had said the words aloud. I started to utter a denial but before I could say a word, Darcy spoke again.

“It is the color of your hair. Father says he knows of only two other people who share it. One is Princess Elizabeth. The other is King Henry. And then there are your eyes. Was Anne Boleyn your mother, too?”

Taken aback, for this was an idea that had never once crossed my mind, I blurted out the raw truth. “My mother was a laundress at Windsor Castle who gave birth to me out of wedlock.” I drew in a steadying breath and then added, with slightly more dignity, “I am a bastard, Master Darcy. A merry-begot.”

“So am I.” He said it as though it did not matter, but I suspected that it did. “Still, I am Father’s heir. And I am not Richard Darcy any longer. Father says I’m to call myself Richard Southwell the Younger.”

“I liked you better with your original surname,” I muttered.

“The Darcys of Essex are my mother’s family.” He elaborated on that subject, but I had stopped listening.

I’d been struck by an intriguing notion. I wondered that I had never thought of it before. The one person who must know who had fathered her child was that child’s mother. To learn the truth about myself, all I had to do was find Joanna Dobson, née Dingley, and ask her.

There was a difficulty, however. I had no idea what had happened to my mother. I did not even know if she was still alive. I had not seen her for fully fourteen years, not since the day the king placed me in John Malte’s care.

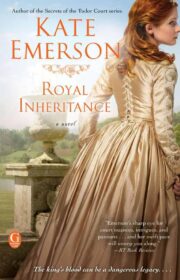

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.