“You have been to court?”

“To visit friends only. I would not live there again for all the world. Do you know that there are now rumors that His Grace tires of Queen Kathryn and would rid himself of her to marry another.”

“A seventh wife!” I clapped my hands over my mouth and felt my eyes widen above my fingers. The words had slipped out unbidden, but that did not make them any less dangerous. It is never wise to criticize a king.

“Have no fear,” Mary assured me. “I’ll not betray you.” Although we were alone, she nevertheless leaned closer and lowered her voice to continue confiding what she’d heard at court. “It is said the king has tired of the queen’s endless lectures on the subject of religion. Her Grace is a confirmed evangelical, advocating all manner of reforms in the church beyond those King Henry has already enacted. He has caused to be issued a new proclamation prohibiting possession of heretical books—the same books known to circulate within Queen Kathryn’s chambers. What happened in Anne Boleyn’s day is happening all over again!”

“But surely Queen Kathryn has not been unfaithful to His Grace!” I thought of that sweet-natured, kindly woman and could not fathom it.

“I meant that Anne was an advocate of Lutheranism and encouraged her ladies to read forbidden tracts smuggled into England by her silkwoman and other friends of reform.”

I was confused, and said so. “The king himself reformed the church. That is why he is now head of the Church of England.”

“There are reforms and then there are reforms. Just as there are many rival factions at court, each party has its own agenda. Did you know that after Queen Jane died, the king briefly fixed on me as a replacement?”

“You might have been queen?”

“You need not sound so astonished.”

“Did you want to be queen?”

“No. Nor did I wish to become a pawn in some political game of chess.” She reached for her goblet, her expression suddenly hard. “If our old friend, Sir Richard Southwell, had had his way, I’d have seduced King Henry into marriage and returned power to the Howards and their clients. He has never forgiven me for failing to cooperate.”

The square of cake I’d just picked up crumbled in my hand. “He is a very bad man.”

She nodded. “And although he claims always to put the Duke of Norfolk’s interests at the forefront, his only true loyalty is to himself. You must never allow yourself to fall under his control, Audrey, else he’ll find a way to use you for his own ends.”

I did not see how he could benefit from an alliance with my family, other than by securing the use of my dowry, but I had every intention of following her advice. “I want nothing to do with him,” I assured her.

We talked of more pleasant matters for a time—fashion and food for the most part. When she asked if I had been to court of late, I admitted that I had not.

“Then come with me on the morrow. I mean to pay a visit to the duchess. She’s had lodgings at Whitehall these last few months, while she’s been attending on Queen Kathryn. She will be happy to see you again.”

I accepted with pleasure.

29

Whitehall, June 10, 1546

We found the Duchess of Richmond in an antechamber in the queen’s apartments, a comfortable little room set aside for quiet pastimes. Several other ladies-in-waiting sat on stools around a low table playing a game of cards. The duchess had been reading. She hastily put her book aside when Mary and I came in, and rose to embrace us warmly, each in turn.

We had scarce begun to exchange news when the Earl of Surrey appeared in the doorway. A ferocious scowl contorted his otherwise pleasant features.

Ignoring everyone else, he stalked toward his sister. Mary and I quickly rose from our places on either side of the duchess and backed away as the earl loomed over her. He did not seem to notice.

“Did you know of this?” His face turned a mottled red as he bellowed the question.

“Know of what, Brother?”

“Father’s grand plan for an alliance with the Earl of Hertford.”

Mary and I exchanged puzzled looks. The Earl of Hertford was Edward Seymour, oldest brother of the late Queen Jane and of Sir Thomas Seymour, Vice Admiral of England. The Duke of Norfolk had not been notably friendly toward any of the Seymours since Jane supplanted Anne Boleyn, Norfolk’s niece, as queen.

Despite her brother’s anger, the duchess remained calm. “Father does not confide in me, Harry. What is he plotting now?” A deep furrow marred the smoothness of her high forehead.

Surrey continued to glare at her. “He means to have you wed Sir Thomas Seymour.”

I gasped. So did two of the ladies playing cards. The duchess’s already fair skin turned whiter still. Beside me, I could feel Mary’s tension as if it were my own.

“There’s more. He proposes that my two sons marry two of Hertford’s daughters.” Vibrating with outrage, his voice rose to a shout. “Who are these Seymours but upstart country gentlemen! Father must be mad to treat with them.”

“They are the brothers of a queen and the uncles of our future king,” the duchess reminded him.

“We have as much royal blood in our veins as Prince Edward!” Surrey raged. “Better you should become the king’s mistress and play the part in England that the Duchess d’Étampes does in France than be married to a Seymour.”

This time the gasps were louder and there were more of them. The earl was oblivious to his audience as he continued to berate his sister. I did not follow most of his rant. I am not certain anyone could have. The shifting allegiances of the court were near impossible to track, even by those close to the center of power. That the duchess had the misfortune to be part of her father’s newest scheme to gain influence at court appeared to be sufficient to bring Surrey’s wrath down on her head. Clearly overwrought, his words were ruled by emotion rather than logic.

“Who is the Duchess d’Étampes?” I whispered to Mary.

“The chief mistress of King Francis of France,” she whispered back.

We retreated farther from the fray but others moved closer, reluctant to miss a word of the earl’s tirade. His ill-considered outburst was the talk of the entire court within an hour. Wagering was heavy that his rash words would have dire consequences the moment they were repeated to the king, but those who thought the earl would be clapped in gaol lost their money. Nothing happened as a result of the incident—no marriages, no alliances, and no arrests.

Or so it appeared at the time.

30

Hampton Court, August 1546

Mary Shelton had been correct about the risk Queen Kathryn had run by preaching to the king. The story was all over London in early August. King Henry had gone so far as to issue an order for the queen’s arrest. Then he had changed his mind. When one of his ministers appeared at court, warrant in hand, King Henry berated him loudly and with as much profanity as he ever allowed himself for daring to suggest that Queen Kathryn was aught but a loving and loyal spouse. To make up for the insult, His Grace showered the queen with gifts. She, having learned her lesson, stopped trying to influence the decisions he made as head of the Church of England.

A few weeks later, on the eve of St. Bartholomew’s Day, a delegation sent by the French king traveled by water to Hampton Court to sign the peace treaty between our two countries. The war was finally over. There were to be ten days of banquets and masques and hunting trips to celebrate.

King Henry sent for his royal tailor. Once again, Father was ordered to bring me along to court.

Tents of cloth of gold and velvet had been set up in the palace gardens at Hampton Court to house some two hundred French gentlemen. Two new banqueting houses had also been erected and were hung with rich tapestries. Awed by all these trappings, I wondered if I would have the courage to carry out the plan I had conceived the moment Father told me that the king wanted to see me.

I meant to demand the truth. His Grace owed me that much, did he not? If the speculation was untrue, then he should be glad to deny it. And if I was his daughter . . . my imagination stopped there. I did not expect anything from him beyond confirmation or denial, but would King Henry believe that? Daily, he was petitioned by hundreds of subjects, all of whom wanted something—lands, money, pardons. I sought knowledge, a far more dangerous thing.

When the king did not send for me, the news that he was to appear at an open-air reception seemed to present me with an opportunity to remind His Grace of my presence. I dressed with great care and left the palace—Father had been assigned both double lodgings and a workroom—to make my way through the grounds.

I stopped some little distance away from the marquee beneath which King Henry stood. His Grace had lost some of his girth since our last meeting. That should have made him appear healthier. Instead he just looked frail.

His clothing was as magnificent as ever, his jewels as plentiful and as sparkling, but he leaned heavily on the shoulder of Archbishop Cranmer, who stood beside him. From time to time, he even allowed the High Admiral of France, the French nobleman who had come to England to sign the peace treaty on behalf of the French king, to support him.

Both the Earl of Hertford and Vice Admiral Sir Thomas Seymour were in close attendance on His Grace. As soon as I recognized the latter, I looked around for Jack Harington. I did not see him at once, but only because of the size of the crowd. I found another familiar face first—that of Sir Richard Southwell.

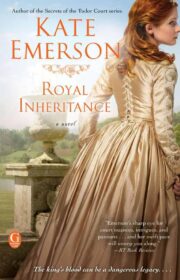

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.