If King Henry had wished to acknowledge me as his bastard, he would already have done so. He had not hesitated to claim Henry FitzRoy and had gone on to create him Duke of Richmond and marry him to the Duke of Norfolk’s daughter.

Rolling over, I punched my pillow into a more comfortable shape. What did I expect? Sons, even those who were illegitimate, were valued. A bastard girl-child had no worth. If the king was my father, I should consider myself fortunate that he’d done as much for me as he had.

Who knew? I wondered. Some might think they knew. Sir Richard Southwell certainly did, else he’d not have been interested in an alliance between me and his son. On the surface, I was only a merchant tailor’s daughter. Father was wealthy, but not excessively so. A match with a country gentleman’s heiress would have been far more appropriate for young Master Darcy.

And Jack? Did he suspect? Was that why he thought he wasn’t worthy to court me?

Then an even more insidious thought crossed my mind. What if Jack did guess and because of that was tempted to change his mind? How would I ever know if he truly loved me or was just interested in me because of my supposed connection to the king?

27

Catherine’s Court, November 1556

You were confused, Mother,” Hester said.

“I was indeed,” Audrey said with a faint smile.

They were still in her bedchamber, where they had spent almost the entire day. Jack would return soon.

“Father loves you for yourself,” the girl said with such confidence that Audrey almost believed her.

“I am tired now, Hester. I would rest awhile.”

“How can you be tired? We’ve done nothing but talk.”

“Reliving my memories is exhausting, I assure you.” She felt passing frail and sapped of strength, as if a good wind could blow her away.

Reluctantly, Hester departed.

Audrey slept.

Somewhat restored, she supped with her husband that evening, feigning an interest in his talk of land and tenants.

“How long do you mean to remain here?” she asked when the last course had been set before them. The cheese and fruit were fresh and flavorful but she had little appetite.

“As long as is necessary.”

“What does the princess mean to do? What is it you want no part of?” Although she applauded his common sense in avoiding trouble, she feared he might already be implicated in whatever scheme was afoot.

“She talks of leaving England for the greater safety of France.”

Stunned, Audrey simply stared at him. France? Their ancient enemy? The place where Tom Clere had been mortally wounded and so many brave English lads had died?

Jack had no difficulty reading her thoughts. “The enemy of my enemy is my friend. Spain wants to invade France. The French king will gladly take in an English princess. The question is whether they will treat her as an honored guest or as a prisoner once they have her.”

“And if she stays in England?”

“She is in constant danger from her sister the queen. You know already that King Philip wants to marry her to his kinsman, the Duke of Savoy. The princess knows what great folly it would be to agree, but her continued refusal may send her back to the Tower.”

Audrey shuddered. “Are you truly safe here, Jack? Will they come after you if they turn on the princess? They must know how much time you have spent of late at Hatfield House.”

“They . . . they will accept another reason for that. If it comes to it, I’ll give it to them.”

Audrey closed her eyes and prayed for strength. It was not as if she had not known about Isabella Markham for some time now. The princess’s maid of honor might not have been Jack’s mistress, but he was most certainly in love with her. Audrey had seen the poems he’d written to the other woman.

“Good,” she said, and excused herself, pleading a headache and saying she would go straight to bed.

She let Edith give her a posset to help her sleep. To her surprise, when she awoke the next day she felt strong enough to agree when Hester suggested they spend the morning on horseback. It would provide another opportunity to continue her tale. It would also be an excellent way for Audrey to avoid speaking to her husband.

Hester was an avid horsewoman. Her father had presented her with a gentle mare as a New Year’s gift the previous January. Since they did not keep their own horses at Stepney, Hester and Fleetfoot, as she had named the mare, had been separated for several months. To make up for her absence, Hester brought several apples to feed to the animal under the watchful eyes of one of the grooms.

“Mustn’t give her too many now, Mistress Hester,” he warned, an avuncular smile on his weathered face. Hester had always been able to charm the servants.

“Saddle her, Parks,” Audrey instructed him, “and saddle Plodder for me.”

The ambling gait of the aging palfrey was all Audrey could manage, even riding astride as they did in the country. She had never learned to be comfortable on horseback, but she could think of no better way to secure the privacy she needed to confide in her daughter. Parks would have to come along for propriety’s sake, but he could ride well behind them, out of earshot.

When they reached the hill that overlooked the house and outbuildings, Audrey resumed her story.

28

June 1546

During the following year I did not see Jack at all, nor was I invited to court by the king. Talks between Sir Richard Southwell and my father continued, although neither seemed in any hurry to formalize the betrothal. The boy they intended for my husband was still at Cambridge.

I, too, continued my studies. I taught myself to read and write musical notation. I had been composing songs to amuse myself for some time but now I had a way to record my music for posterity.

In June, quite unexpectedly, I encountered Mary Shelton again. There was a gathering at the Merchant Taylors’ Hall, which is situated near Bishopsgate Street. I had been suffering from a wretched headache all that day. The noisy crowd inside the hall made it worse and I begged to be excused from the festivities. With Edith accompanying me, I left through a side door. What chance took me in that direction, I do not know, but as I emerged onto the street, I recognized Mary just passing by with her own maid and a groom.

She had been shopping, for the maid was juggling a half-dozen parcels and the groom carried a large bolt of cloth. Instead of mourning, she wore bright colors, and on one finger was what was unmistakably a wedding ring.

When we had exchanged delighted greetings, she invited me to accompany her back to her brother’s house, where she was staying while in London. The ache in my head having miraculously vanished, I accepted with enthusiasm.

We did not have far to go. Sir Jerome Shelton lived within the close of what had once been the priory of St. Helen’s, Bishopsgate.

“Is this where your namesake was a nun?” I asked when we had settled into a luxuriously appointed chamber with cakes and ale and dismissed the servants.

Mary laughed. “It was. Poor old thing. These days she is obliged to live out in the world, and on a paltry pension of four pounds per annum, too.”

“She could marry, I suppose.”

But Mary shook her head. “It is forbidden for the former religious to wed. A foolish ruling, if you ask me. But no one did.” She sipped thoughtfully, then put her goblet aside. “You are doubtless wondering how I could wed another with Tom so recently dead. I will save you the trouble of finding a tactful way to ask. I wanted children. I have for a long time, and it is problematic to conceive one without a husband. Having near to hand an older cousin, a widower of whom I am very fond, I married him.”

“But, Mary,” I blurted out, “if you longed for children, why did you never marry Tom Clere?”

She fiddled with the ribbons she’d just removed from one of her parcels, avoiding my eyes. But after a moment, impertinent though my question had been, she answered it.

“I could not. After the debacle at court with Southwell, I foolishly agreed to a match my father arranged for me with a Norfolk gentleman. Because I hadn’t the sense to refuse that legal entanglement, our pre-contract prevented me from marrying anyone else while he lived. He’s dead now,” she added, “but he did not have the courtesy to leave this world until my Tom was no longer in it, either.”

I had always appreciated her candor and tried to answer it in kind. “Children will bring you the happiness you deserve.”

“So I do hope. And I am content with my choice of a husband.”

“Is he here with you?”

“He remains at Ketteringham, his country estate, while I, and his heir”—she patted her still flat belly—“spend the summer in London, badgering the courts to confirm the grant of lands in Hockham Magna that Tom Clere left to me in his will.”

I thought better of pointing out that her new husband could fight her legal battles for her. “In truth,” I said instead, meaning every word, “I envy you. I would like to have children someday, but I do not care for the father my father proposes for them.”

“Somehow I thought you and Jack Harington would marry one day.”

“That was my hope, too, but he . . . that is, I do not even know where he is.” I sighed deeply. “He could be dead for all I know.”

“He is not dead. He’s in Calais, which may amount to the same thing,” she added with a grin. “This endless war with the French takes all the best men away. Always excepting gentleman farmers like my new husband. Even the king is melancholy.”

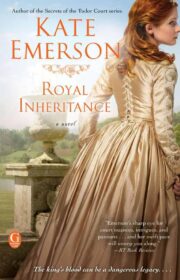

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.