“How far away is Dover?” I asked Edith after Jack had left us.

She gave me her usual disapproving look and answered in a taut voice. “It is a journey of two or three days. Not one to be undertaken on a whim or without proper escort.”

I knew already that I could follow Watling Street, which had started life as one of the old Roman roads, nearly all the way there, but for the nonce I was forced to accept that it would be some time before I saw Jack Harington again. This did nothing to lessen my determination to be reunited with him at some point in the future.

As usual, I remained in London throughout the summer.

In July, a ship called the Hedgehog blew up on the Thames at Westminster. The explosion could be heard everywhere in the city. We were fortunate indeed that the fire did not spread to any houses.

The very next day, in Portsmouth, where the king and the Earl of Surrey and the English navy had been gathering to repel the expected invasion by a French armada, a much more important ship, the king’s own Mary Rose, sank in the Solent. King Henry, it was said, watched helplessly from the ramparts of Southsea Castle as almost all aboard were lost. In an entire summer, the French fleet did less damage to morale.

Shortly thereafter, the Duchess of Richmond returned to Kenninghall. She took Mary Shelton with her.

In all, it was difficult year, filled with bad weather and bad luck. A great tempest struck Derbyshire, Lancashire, and Cheshire. A dearth of corn and victuals affected every county. There was famine, and the sailors manning those ships at Portsmouth suffered from an epidemic of the bloody flux followed by an outbreak of the plague. The only good news was that the French fleet turned tail and sailed back to France.

I prayed nightly that Jack would remain safe in Dover with Sir Thomas Seymour, but in September Sir Thomas was relieved as acting warden and took up new duties with the fleet in Portsmouth. Jack stopped at the house in Watling Street on his way through London, but only long enough to pay his respects. Father and Mother Anne were present throughout his visit and he said nothing to indicate he had any interest in asking for my hand in marriage.

Father saw him on his way. By the time he returned to the hall, Mother Anne and I had resumed work on a large piece of embroidery held in a wooden frame.

“Sir Richard Southwell has settled Horsham St. Faith and other properties in Norfolk on his son,” Father announced.

“A gentleman’s portion.” Mother Anne looked approving. “And young Richard will be entering the Inns of Court ere long. The law is a respectable profession, and lucrative, too.”

I feigned a yawn. Country gentleman, courtier, or solicitor, it made no difference to me. I did not intend to marry the offspring of a murderer.

Determined upon resistance, I ignored every effort to change my mind. Lectures from Mother Anne did not move me. Father tried logical arguments, stressing the advantages of marriage to a comfortably well-off husband. I affected deafness.

It would not be so very bad, I thought, to continue just as I was and never marry. I filled my days with music and reading, sewing and works of charity in the parish. I had Father and Mother Anne close at hand and sisters nearby. I had Pocket, who loved me unreservedly. I told myself I was both happy and content.

I lied.

26

December 1545

King Henry spent the last part of the year in Surrey, moving between Nonsuch, Petworth, Guildford Castle, and Woking, but when he came to London for the opening of Parliament, he sent for me. It was the first time I’d seen him since that long-ago progress, more than two years earlier, when I had met Prince Edward and Princess Elizabeth.

Once again we met at Whitehall, this time in the privy gallery that overlooked the gardens. The king, even more obese than when we’d last met, sat in a wheeled chair. He had no reason to rise when I entered and made my curtsey, but I had to wonder if he could. All that had once been muscle had turned to fat. His Grace had always had small eyes, but now they were nearly swallowed up by the abundant fleshiness of his face. A faint, unpleasant odor clung to him, in spite of the strong sweet perfume he wore.

“How is that little dog we gave you, eh?” the king asked.

Father had prudently retreated. The king’s attendants also moved out of earshot.

“Pocket is well, Your Grace.” I did not think I should mention that my dog, like my king, showed the effects of overindulgence in rich food. Early on, Pocket had learned to beg table scraps from me and my sisters. Even Bridget had tossed him choice bits of meat and bread.

For several minutes, the king spoke of trivial matters. I was considering how to broach the subject of Father’s post as royal tailor, in the hope of preventing its loss to Richard Egleston, when King Henry placed one bloated hand on my arm. His words, although gently spoken, had the force of a command.

“It is our wish that you wed young Richard Darcy.”

I bit back my first response, well aware of the folly of outright refusal. “I am too young yet to wed,” I temporized.

The king chuckled. “Many girls your age are not only married but mothers twice over.”

Greatly daring, I answered him. “And many wait until they are five and twenty, with a good dowry saved up and a chest full of linens ready for their new home.”

Maidservants like my Edith, if they wed at all, did not do so until they were able to afford to leave service entirely. Some never reached that point. Or they failed to find anyone to marry them.

“You may wait awhile if it is your wish, Audrey,” the king said. “It is true that you should come to the marriage with a proper dowry. It is a father’s duty to provide one. We will talk with Malte about that, never fear. But marry young Darcy you must. I have promised his father.”

I could not bring myself to agree, but I dropped into a subservient curtsey in the hope that the king would not ask for more. His Grace seemed satisfied. When I rose, he waved me away. Father was waiting to lead me back outside.

“His Grace is not well,” I said as we made our way to the water stairs.

“No, he is not. He must use what he calls ‘trams’ to get around inside the palace and there is a winching device in use to hoist him up flights of stairs.”

“His Grace should lose some weight.”

Father stumbled on the uneven walkway and I had to catch his elbow to keep him upright. “Pray do not tell him so. I should hate to see you sent to the Tower.”

“His Grace does not hesitate to tell me how I should proceed.”

“That is his prerogative. He is your liege lord. You owe him obedience.”

“I will not marry Richard Darcy.” I grew tired of repeating this, but no one ever listened.

“If you think to wed young Harington instead, abandon that idea at once. He is no fit match for you.” Father signaled for a boatman to bring his watercraft closer and offered a hand to help me climb in.

I ignored it and managed by myself, muttering under my breath that if that were the case then I would not marry at all. I’d said that before, too, and had not been believed. Every woman was supposed to want a husband and children.

We made the journey back to London in stilted silence. I did not want to talk anymore about marriage or betrothals or dowries. I recognized Father’s right to make such arrangements for my future, but what business was it of the king’s who I wed or when? That Sir Richard Southwell had somehow influenced King Henry made everything worse.

Home again, I said as much to Edith as she helped me out of the elaborate clothing I had put on for my visit to the court: “Why should His Grace care who I marry?”

“The king has known you since you were a little girl,” Edith said. “He is fond of you and wants what is best for your future.”

“He should let me decide that.”

“Choosing a girl’s husband is her father’s responsibility. A daughter has a duty to obey her father and we must all obey our king. In this case, your obligation is one and the same. You must marry Richard Darcy.”

One and the same.

Those words stuck in my mind, taunting me during the long, sleepless night that followed, forcing me to remember the suspicions I had chosen to forget. On the day I’d seen my own features reflected in those of Princess Elizabeth I’d wondered if I’d been told the truth about my parentage. Young as I was, I’d been aware of the speculative glances, the knowing looks. I’d shoved my suspicions aside when Father insisted that I was his child, but what if he had only meant I was his by adoption? He called Mother Anne’s Elizabeth and his first wife’s daughter, Mary, his children, too.

I had no doubt but that he loved me and thought of me as his daughter, as he did Mary, Elizabeth, Bridget, and Muriel. And yet two, perhaps three, of us were not his kin at all.

Was King Henry my real father? Was that why he had rescued me from the man my mother married? Was that why he had taken an interest in my upbringing all these years, giving me Pocket to care for, sending tutors to me, inviting me along on one of his progresses when the danger of plague in London was higher than usual? Was that why he sought to force my marriage to the son of his old friend, Sir Richard Southwell?

There was no one to answer my questions. Father would simply repeat that I was his daughter. I wished I had thought to ask the king, but I knew full well that even if I had thought of doing so, I’d never have dared. To blurt out such an impertinent question, whether or not I had royal blood running through my veins, might well send me to the Tower.

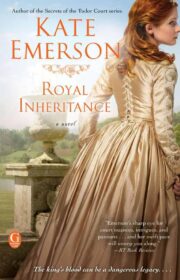

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.