“Father, I—”

“Go upstairs at once,” he bellowed at me.

“You are not to hurt him!” I shouted back, seeing that his hands were raised to throttle Jack. “The kiss was my doing.”

“To your chamber, Audrey. Now.”

This time I obeyed, but I stole one last glance at Jack as I went. The expression on his face warmed my heart. It was not the look one friend gave another. In spite of the imminent threat that Father might thrash him, he wore a silly grin. My kiss had finally forced him to accept that he had feelings for me.

25

1545

I did not see Jack again for many months, or hear from him, either. In the interim, Muriel wed John Horner. Father temporarily abandoned negotiations for my marriage to Richard Darcy, but only because he had other matters to concern him. Richard Egleston, who had been Father’s apprentice and was married to Mary, Father’s first wife’s daughter by her first marriage, had begun a campaign to replace Father as the king’s tailor. He claimed Father was too old to perform his duties. This was arrant nonsense, but Egleston had made powerful friends among the other artisans at court, some of whom had long been envious of Father’s favor with the king, and they supported his suit.

In April, Bridget gave birth to a son she named Anthony. Anthony Denny, who had been knighted by the king and was now Sir Anthony, was one of the boy’s godfathers. Bridget often brought the baby with her when she came to visit Mother Anne. On these occasions she regaled us with all the news her husband, John Scutt, had lately brought home from court. Most were tidbits Father had been too preoccupied to mention.

“It is all the talk at court, or so Master Scutt tells me.” Bridget handed little Anthony to Mother Anne to make much of and fixed her bright-eyed stare on me. “The Earl of Surrey’s squire left all he had to Mary Shelton. She was his mistress, they say, for it is certain they never married.”

“They planned to wed.”

The news that Tom Clere had succumbed to his wounds saddened me. I had never known him well, but I had seen him with Mary and knew they loved each other deeply. I had hoped he’d recover from the injuries he received in France. He’d lingered nearly seven months.

How terrible his suffering must have been. Had he known all along that he was slowly dying, or had there still been some hope for his recovery? Either way, how devastating his death must have been for poor Mary.

Bridget felt no such stirrings of sympathy. “She should have married him long since, then, old as she is! And since Clere did come home from the war, why not wed on his deathbed? Then she’d have inherited as his wife and have avoided all this furor.”

I had no answer to give her. Mary was more than ten years my senior. What was more surprising was that her father had not arranged a marriage for her. I wondered if he was still living. I had no idea. I had never asked.

Having failed to pick a quarrel with me, Bridget moved on to other scandals. I soothed myself by stroking Pocket, who lay curled in my lap. He licked my hand. He was no longer young. I’d had him more than seven years. He’d gotten fat and lazy and spent most of his time sleeping in front of the fire.

Father, upon being questioned, recalled that Tom Clere had been buried at Lambeth only a few days previously. The Earl of Surrey had written his elegy.

Thoughts of Mary Shelton and her lost love haunted me all the rest of that day and half the night. The next morning I sent a message of sympathy to Norfolk House. An invitation to visit arrived later the same day.

Little seemed to have changed at Norfolk House in four years, except that everyone was older and I was much more finely dressed than I ever had been as a girl. The exception was Mary Shelton. Black-clad, her face showed the ravages of long sleepless nights of weeping.

“Come, Mary,” the Duchess of Richmond said in a bracing voice. “Greet our guest.”

Lady Richmond, at least, was just as I remembered her, right down to the spaniel on her lap. I did not suppose it was the same one, but it might have been.

Mary required a moment to recognize me. “Audrey?” Her pale blue eyes narrowed. “How long has it been? You are a woman grown, and the resemblance is even more remarkable.”

Taken aback, I blinked at her. “I beg your pardon?”

“She is rambling again,” the duchess cut in. “Come and see Father’s new garden.”

We went outside, with Edith and several other waiting women trailing behind, but while Lady Richmond sang the praises of the Duke of Norfolk’s head gardener, who had coaxed violets, periwinkle, and bluebells into flowering, I stole sideways glances at Mary. She showed no interest at all in the early variety of rose the duchess was showing me. After a moment, she withdrew a piece of paper from the pocket concealed in her black damask skirt. She did not unfold it. Merely looking at it made her cry. As tears streamed down her cheeks, a tiny sob escaped her.

The duchess whirled around with a sound of disgust, dropping the rose. “Give that to me!”

When she would have snatched the paper out of her companion’s hand, Mary clutched it to her bosom and backed away. “It is precious to me.” She sent a pleading look in my direction, over Lady Richmond’s shoulder. “Do not let her take it, Audrey. It is a copy of the elegy my lord of Surrey wrote to honor Tom.”

“And you know it by heart,” the duchess snapped. “As do I!”

“It is a beautiful poem!” Again Mary looked to me for help.

I wanted desperately to do something to ease her despair. “I have not heard this poem. Will you recite it for me?”

Smiling through her tears, she did so:

Norfolk sprung thee, Lambeth holds thee dead;

Clere, of the Count of Cleremont, thou hight.

Within the womb of Ormond’s race thou bred,

And saw’st thy cousin crowned in thy sight.

Shelton for love, Surrey for lord thou chose;

(Aye me! whilst life did last that league was tender).

Tracing whose steps thou sawest Kelsal blaze,

Landrecy burnt, and batter’d Boulogne render.

At Montreuil gates, hopeless of all recure,

Thine Earl, half dead, gave in thy hand his will;

Which cause did thee this pining death procure,

Ere summers four times seven thou couldst fulfill.

Ah! Clere! if love had booted, care, or cost

Heaven had not won, nor earth so timely lost.

“It is a fine tribute,” I said, although I had not understood most of the references.

“Better than any of the three poems his lordship wrote when Sir Thomas Wyatt died.”

The duchess rolled her eyes. “Well, then. You have recited the elegy. Put the paper away and come and sit in the shade of the rose arbor. We will talk of happier things. It is what Clere would have wanted,” she added when Mary began to protest. “He much disliked excessive mourning and well you know it.”

Mary’s grief and unhappiness could not so easily be set aside, but when she entered the duchess’s service she had sworn to obey her mistress. With at least the appearance of meekness, she did as she had been told.

The garden was lovely, colorful, and soothing to look at. Delicate scents filled the air. The faint buzz of insects and the distant shouts of watermen on the Thames were the only sounds to intrude on the peaceful quiet.

“Do you still write poetry?” the duchess asked me, breaking the silence.

“I have not done so lately, Your Grace.”

“But you still sing, I warrant.” She sent one of her maids indoors to fetch a lute. “Will you play something cheerful? One of your own compositions, perhaps?”

I did so, and after that one of the king’s songs. Then the duchess persuaded Mary to sing with us a piece written to be performed in three parts. By the time we had achieved some semblance of harmony, the faintest of smiles played upon Mary’s lips.

I returned to Norfolk House the following day, at the duchess’s invitation. To my astonishment, she had also invited Jack Harington.

“Come and tell us of your exploits.” She patted the cushion beside her on the window seat. A steady rain fell beyond the panes, discouraging us from venturing outside.

“There is not much to tell, my lady. On a ship, a great deal of boredom broken only by short periods of sheer panic. In truth, I prefer to fight on land.”

“That anyone should wish to fight at all is madness,” Mary said with something of her old blunt outspokenness.

Jack sent a sympathetic look her way. The duchess ignored her.

“Will our troubles with France ever be over?” I asked. “I thought the war ended months ago when the king came home.”

“King Henry returned, but not his troops,” Jack said. “The French do not give up easily. Their fleet continues to harry our coast.”

“There’s talk at court of a curfew in London,” the duchess remarked.

“And perhaps a special watch of citizens from nine at night until four in the morning,” Jack agreed. “Everyone needs to be on the lookout for French agents. They are more than capable of planting explosives that could set the entire city on fire.”

The very thought terrified me. Wooden buildings and thatched roofs burn quickly. It would not take much to start a conflagration that would spread from house to house, street to street until there was nothing left of London but ashes.

Seeing the color drain from my face, Jack leapt to his feet and took my hands in his, murmuring comforting words. Mary’s eyebrows lifted but she made no comment.

We both stayed to dine and later that day, after the rain stopped, Jack escorted me home. He did not speak of the kiss we’d shared when last we’d been together. Nor did he give any indication that he intended to see me again. He left me at the gate to the yard—out of sight of father’s shop—without lingering. His parting words were a reminder that he was the vice admiral’s man and therefore was expected to remain close to Sir Thomas in Dover. They would be there for some time to come. Sir Thomas had been named acting warden of the Cinque Ports.

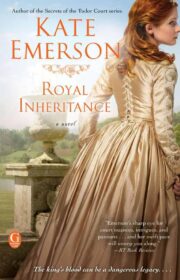

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.