“The queen means to go on progress next month through Surrey and Kent.”

“There is a royal progress every year,” I said impatiently. “That is not news worth sixpence. I’d value it at less than a farthing.”

“She will take the royal children with her.”

“A penny’s worth. No more.” And not enough to account for Bridget’s barely suppressed glee.

“Master Scutt has seen the itinerary.”

I said nothing to this. A list of stops proposed for the progress did not interest me and I had vowed never to ask why, months after their wedding, Bridget did not yet call her husband by his Christian name. I did not want to be privy to the intimate details of their marriage.

“The queen will stay at Mortlake, Byfleet, Guildford, and Beddington,” Bridget continued, “and at other great houses, too. Her Grace will honor friends at Allington Castle and Merewood with brief visits.”

I pantomimed a yawn. Bridget’s answering scowl pleased me very much.

“Do not tease her, Audrey, I beg you.” Muriel looked truly distressed. “Bridget may decide not to tell us anything exciting, after all.”

“She cannot have a very important secret. If it had to do with the king or the queen, the gossips of London would already have caught wind of it.” Nothing spread faster in the city than a rumor.

Two bright spots of color appeared on Bridget’s cheeks. “At Merewood the queen’s host will be Sir Richard Southwell,” she blurted.

I paused with a comfit halfway to my mouth. My appetite for the sweet abruptly vanished. “Sir Richard Southwell is nothing to me.”

“Is he not? He made a great impression on you the first time you saw him. Do you remember, Muriel? Audrey came home from visiting her fine friends at Norfolk House all aghast at having been in such proximity to a man who had gotten away with murder.”

Muriel shivered. “I remember. You did not like him, Audrey. And you did not like that he had been pardoned.”

“Be that as it may, Sir Richard Southwell has naught to do with me.” I might not have been able to recall telling my sisters about that initial encounter with him, but I was certain I had never mentioned meeting him again at Ashridge. I had tried very hard to forget it had ever happened. Just thinking about the fellow left a bad taste in my mouth.

“Master Scutt,” Bridget announced, “says that Sir Richard will be coming to London soon to talk to Father.”

“Does he need a new suit of clothes?” I threw out the question with what I hoped was a careless air, but my heart was starting to beat a little faster. Bridget was leading up to something and, knowing Bridget as I did, it was not news that would please me.

“He needs a wife for one of his bastard sons.”

“Too late. Muriel is betrothed to young Master Horner and Father has already picked out a likely prospect for me. A Cambridge scholar, no less.”

Bridget laughed. “Is his name Richard Darcy?”

I nodded. Never mind that I’d not cared for him the one time we’d met. I’d take him, gangly arms and legs, tongue-tied mumblings, and all before I’d consent to marry the merry-begot of a murderer.

Bridget’s eyes glittered with a malice she did not trouble to conceal. “Richard Darcy, sister dear, is Sir Richard Southwell’s bastard son.”

24

I told Father I would never wed Richard Darcy. I even told him why.

He assured me that, given time enough, I might well change my mind. “Get to know the lad,” he urged me, as he had after Bridget’s wedding. “Marriage to a gentleman, Audrey, is not to be scoffed at.”

“He is no gentleman. Sir Richard got him on a mistress. And he cannot be the heir so long as there are legitimate children.”

“The late Lady Southwell bore Sir Richard only a daughter,” Father said, “and so young Richard is his eldest son. He will come into a goodly patrimony. Besides that, his father has often said that he will marry the boy’s mother when he can and make her the new Lady Southwell.”

“If he is already a widower, why has he not done so ere now?”

Father looked uncomfortable. “She has a husband yet living.”

“I am surprised Sir Richard does not simply murder him.”

“A man should be forgiven one mistake,” Father chided me. “The king himself pardoned Sir Richard.”

“Perhaps the king made a mistake!”

Father’s eyes went wide. Then he looked uneasily around to make certain no one had overheard my outburst. We were in the shop, but the apprentices had all been sent out on various errands and there were no customers. Father kept his voice low regardless. “You must never say such a thing again. The king is always right.”

Shaken by how tense he had become, I hastened to apologize. “I beg your pardon, Father. I misspoke.”

He pretended to believe me. And he ignored the rest of what I’d said. Negotiations for the match with Richard Darcy went forward. I reminded myself, having witnessed the process with my older sisters, that it could take as much as two years to work out all the details of a marriage contract. I had plenty of time to talk Father out of marrying me to Sir Richard Southwell’s son.

King Henry returned to England at the end of September.

In October, quite by accident, I saw Jack Harington again. He was standing in front of the Sign of the Green Cap, a bookseller’s shop, absorbed in a book of Latin poetry. More than a year and a half had passed since I had last set eyes on him. He was much changed in appearance but I recognized him at once.

I had time to take his measure before he noticed me. He was better dressed than he had been in the old days, but he had lost weight. His face, in spite of a newly acquired beard, had a pinched look. His eyes, when he sensed the intensity of my gaze and glanced up, had the sunken appearance that came from too many nights without sufficient sleep.

My first thought was that he had been out carousing but I was quickly disabused of that notion. Dissipation has a different look. I’d seen it in the Earl of Surrey and some of his friends but it was utterly lacking in Jack Harington. Whatever had left Jack with that bleak expression, it had not been wine and women.

“Mistress Audrey.” He returned the volume to the bookseller’s stock, displayed on a wooden pentice. At night, the books were removed and the pentice used to cover the open front of the shop.

The act of doffing a cap and bowing meant nothing of itself, but what I saw in his expression warmed me. He was genuinely glad to see me.

“Master Harington. I did not know you were back in England.”

“Only just. Have you come to make a selection?” He gestured toward the offerings; everything from broadsides to Bibles vied for space with Greek plays—in Greek—and printed copies of sermons.

“Only if there are songbooks.”

“I’ve not seen any.”

“How disappointing, but I am not surprised. At the two other booksellers I’ve visited this morning, I found naught but liturgical service-books containing plainsong with Latin words.”

“I am pleased to hear that you have continued with your music.”

“How could I not, when I had such an enthusiastic tutor? But I suspect that my life since last we met has been very dull compared to yours. Will you tell me of your travels?”

Belatedly slapping the hat back onto his head, he said, quite firmly, “I will.”

Then he made so bold as to take my arm and lead me a little apart from the noise and confusion of the street. Edith kept pace with us, disapproval writ large on her countenance. I ignored her. Jack’s manner thrilled me and his touch sent tingles of pleasure throughout my body.

There were no convenient benches to sit upon so we kept walking, wending our way through quiet alleys and lanes to avoid the main thoroughfares. I did not care where we went. I was happy just to be in Jack’s company.

“I have found some measure of success in Sir Thomas Seymour’s service,” he confided as we walked. “As Sir Thomas prospers, so will I. He keeps me close and employs me as a messenger when he has important communications to send. I deliver his letters and return with the replies. Princes, generals, margraves—I have met them all.”

“Where did you go first?” I asked. “You were bound for the Low Countries when you left England.”

“To Brussels, to the court of Mary of Hungary, Regent of the Netherlands. She is a most remarkable woman.”

“I know nothing of foreign princes,” I admitted. “Who is she?”

“You will recall that King Henry’s first wife was Catherine of Aragon, a Spanish princess. This Mary is her niece, and the sister of Emperor Charles V. It was Mary’s brother who appointed her to rule over the Low Countries upon the death of another aunt, Margaret of Austria.”

“Are the regents always women?” I was remembering that, until he’d returned a few weeks earlier to reclaim the reins of government, King Henry had entrusted Queen Kathryn to rule England in his absence.

“It is somewhat unusual, but then Mary of Hungary is an unusual woman. She is always flinging herself upon horseback and riding off to one place or another. Her courtiers can barely keep up with the pace she sets. Why, once she made the seventeen-day ride from Augsburg to Brussels in just thirteen days!”

I made an appreciative sound but, in truth, I had no notion what this accomplishment entailed. My journeys, save for that one year when I’d been summoned to join the royal progress, had all been short ones. When I traveled, it was most often by water. In all my sixteen years, I had never ridden a horse by myself, but only on a pillion behind a man’s saddle.

“Sir Thomas enjoyed Brussels, as did I, but he was ordered back to Calais after only a few months. That he was appointed marshal of the army made up for any disappointment. The invasion of France should have taken place then, but first King Henry had to deal with the Scots.”

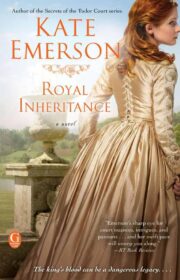

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.