She could not fault her husband’s loyalty to Princess Elizabeth, or to the religious faith in which they’d both been reared, but so long as Mary sat on the throne, either allegiance might have deadly consequences. The fires of Smithfield burned bright to consume so-called heretics. A dank, cold cell in the Tower awaited those judged to be traitors, followed by the most terrible and ignominious death imaginable—to be hanged, drawn, and quartered, the severed parts afterward displayed to strike fear into all who saw them.

A shudder racked Audrey’s thin frame. Only a few months earlier, the so-called Dudley Conspiracy had come to light. Jack had sworn he was not involved with the conspirators and she’d believed him, but he was plotting something now. She was certain of it.

“You cannot help the Lady Elizabeth if you are in prison, or if you are dead.”

“Would you have me run away? Go into exile in France or the German states?”

“Others have, there to wait for the queen to die. Mary has borne no child and likely will not, given her age. In time, Elizabeth will succeed her half sister.”

“How much time? We have already waited three long years.”

“As long as it takes! Think of your daughter, Jack, if not of me! If you are condemned, your estate is forfeit. She will be left destitute.”

“You have kin who will take you in.” His cold voice held no hint of the laughing young man Audrey had once known.

“I’d rather beg in the street than throw myself on Bridget’s mercy.”

“You—”

“There is no one else, Jack. No one. Father, Mother Anne, and Muriel have all gone to their reward. My family consists of you and Hester and I will fight for what is best for our child.”

He drew in a deep breath and ran the fingers of one hand through his thick, dark hair. He’d grown a beard since she first knew him, a luxuriant thing with a mustache above. He tugged on it, as if debating with himself how much to tell her.

“Have I ever betrayed you?” she asked.

He sighed again. “No. But the less you know, the better. All this may come to nothing.”

“They why do we flee London? For that is what you are doing, Jack. Running away.”

“Running to,” he corrected her. “To safety.” The rueful sound he made was not quite a chuckle. “I should think you’d be pleased about that.”

“So you have done nothing yet to incriminate yourself?”

“Naught but listen.”

That meant it was Princess Elizabeth who was planning something dangerous, Audrey thought. “Has she asked you to assist her?”

“No, she has not.”

Audrey thought some more. It was no secret that Queen Mary wanted her half sister to wed the Duke of Savoy. Once married, King Henry’s troublesome younger daughter, Mary’s heir so long as she bore no child of her own, would fall under the control of a husband who was not only Mary’s ally and a good Catholic, but a foreigner. He could take the princess out of England and keep her away.

“I pray every night for a return to the Church of England and an end to Spain’s influence,” she said in a hoarse whisper, “but treason is a fool’s game.”

“Do you not think I’ve learned that? I’ve seen far too many men I admired go to their deaths because they acted against those in power. My one desire is to keep Elizabeth safe from harm. She has only to survive to one day succeed her sister, peacefully and without civil war. There has been enough blood spilt.”

So passionate was this declaration that Audrey found herself unable to argue with it. She slid her arms around her husband’s waist and simply held him for a long moment. Then she pulled away and announced in a brusque and businesslike voice that she would have the household ready to leave Stepney within two days.

Two hectic weeks later, they were settled in at Catherine’s Court. During that time, there had been no opportunity for Audrey to share further confidences with her daughter. She had warned Hester not to speak of what she had already learned. She felt strangely reluctant to have Jack find out what she had begun. She did not think he would approve.

Audrey was still in her bedchamber, breaking her fast with bread and cheese and ale, when Hester burst into the room. “Father has gone off with his steward to tour the estate!” she announced. “He will not be back for hours and hours.”

Her daughter’s excess of energy made Audrey feel tired just looking at her, but what the child wanted was abundantly clear. And she was correct. This was the perfect time to resume her narrative.

22

April 1544

Another war with both France and Scotland seemed imminent in the days just before my sister Bridget married John Scutt. Like Father, he was a royal tailor. A few years earlier, he had been master of the Merchant Taylors’ Company.

He had been courting Bridget for the best part of two years, giving her all the traditional gifts a young lover sends to his future bride. But he was not a young lover. He was nearly fifty to Bridget’s seventeen and had been married twice before. He had a daughter, Margaret, who was eight years old. But he was very wealthy.

Bridget greedily accepted everything he offered—coins, rings, gloves, purses, ribbons, laces, slippers, kerchiefs, hats, shoes, aprons, hose, whistles, crosses, lockets, brooches, gilt knives, silk smocks, a pincase, garters fringed with gold, and even a gown with satin sleeves. As we had all been encouraged to since earliest childhood, she’d stitched linens against the day she’d marry. She had accumulated a goodly supply and Father was prepared to provide anything else that was necessary for her to set up housekeeping.

“But will you be happy with Master Scutt?” Muriel asked her as we dressed her for the ceremony in a new russet wool gown with a kirtle of fine worsted. It was a lovely spring morning. Even London’s air seemed fresher than usual. Our bedchamber was filled with the mingled scents of rosemary, to strengthen memory, and roses, to prevent strife.

Bridget laughed and tossed her long yellow hair, worn loose down her back like a veil on the occasion of her wedding. “He is besotted with me and I mean to keep him so.”

“But he is so old,” her sister persisted.

“If he cannot keep me satisfied,” Bridget confided in a whisper, “I know how to find those who can.”

“Really, Bridget,” Mother Anne chided her, “you should not say such things, not even in jest.”

“Are you certain I am jesting?”

“You had better be. You may not have experienced it yet, but Master Scutt has an evil temper when he feels he has been wronged. You would be wise never to provoke it.”

Bridget only laughed some more. I was the one who worried. Although it rarely deterred any female from marrying, it was common knowledge that after the exchange of vows a husband took control of every facet of his wife’s life. He owned everything that had once belonged to her. She was beholden to him for the clothes on her back and the food on their table. Worse, he could beat her if he chose, and no one would intervene. Once they were one in the eyes of God, he acquired ownership of all her possessions and also of her person. She was as much his chattel as a sheep or a cow.

Muriel and I had spent the last several days before the wedding knotting yards of floral rope. This now hung on every wall of the house. As Bridget’s attendants, we had one more duty. We set to work stitching ribbon favors to her bodice, sleeves, and skirt.

“Baste loosely,” Mother Anne warned us. After the ceremony, these favors would be tugged free by the wedding guests.

When she was ready, Bridget smirked at herself in the looking glass. She did look very fine, even though she wore only two pieces of jewelry. The “brooch of innocence” was prominently displayed on her breast. A gold betrothal ring glinted on one finger. Muriel handed her a garland made of rosemary, myrtle leaves, and gilded wheat ears to carry to the church. That done, we three set out to walk the short distance west along Watling Street from Father’s house to St. Augustine’s church.

The entire way was strewn with rushes and roses and our neighbors had turned out in force with makeshift instruments, everything from saucepan lids and tin kettles with pebbles inside to drums made of hollow bones. It was an old, old tradition—the noise was supposed to keep evil influences away.

The ceremony was one I’d witnessed many times before. I scarce listened to the droning words but the scene itself affected me strongly. In my mind’s eye, I did not see Master Scutt. Jack Harington stood there, plighting his troth, far more toothsome, and with more teeth left, too. In Bridget’s place, I imagined myself, face radiant, heart slamming against my ribs in anticipation of spending the rest of my life with the man I loved.

“Love, honor, and obey,” I whispered along with my sister, “till death us do part.”

I snapped back to reality when the wedding sermon began. It dealt with the duties of wedlock. The groom was urged to be tolerant, the bride faithful. I wondered if Bridget had any intention of keeping that vow. Most assuredly, she would never stop flirting with any man who appealed to her.

But for the present, the new husband and wife were in harmony. They passed the bride cup around to all the guests. Sops—small pieces of bread—floated in the wine. Before each person drank, he or she dipped a sprig of rosemary into the contents of the cup.

Afterward, everyone returned to Father’s house. A great feast had been prepared, but first Muriel and I had another tradition to uphold, that of breaking a cake over the bride’s head and reading her future in its pieces. It is possible that I enjoyed this act a bit more than I should have, and left a great many more crumbs than necessary ground into Bridget’s long yellow hair, but the chunks that fell to the floor foretold much that was desirable—a son and heir and great wealth. Pleased, Bridget contented herself with finding occasion to pinch me—twice—during the festivities.

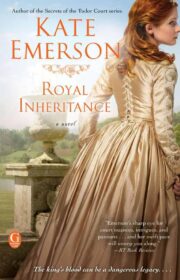

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.