The queen’s rooms were so much grander than Prince Edward’s that I could not begin to imagine what the king’s apartments must be like. Sumptuous tapestries showed scenes of hunting and hawking and even the less expensive verdure tapestries used as window-pieces were worked with allover patterns of foliage. Gold and silver threads made them sparkle. There were more Turkey carpets than I’d ever seen in one place before, on cupboards and sideboards and even on the floors. The queen’s chair was upholstered in cloth of gold and red velvet with gilt pommels and roundels of the royal arms. There were plump cushions for everyone else to sit upon, when the queen permitted. These were arranged on window seats, chests, benches, and stools.

The queen fit in well with such grandeur. Jewels adorned both her clothing and her person, especially diamonds. She was a surprisingly tiny woman, even smaller than the king’s last wife. I was several inches taller and I had not yet reached my full height.

Queen Kathryn seemed as curious about me as I was about her and watched me closely as I approached. Although Her Grace had been twice widowed before she married King Henry, she was not yet thirty. Even at a distance, I could see that her skin was as smooth as that of a much younger woman. I learned later that she made a practice of bathing in milk.

One of the queen’s carefully plucked eyebrows lifted perceptibly when I reached her chair. Her hazel eyes narrowed.

I dropped into a curtsey, bowing my head to hide my own expression. I did not want her to see how nervous I was, and how insecure about my appearance. I was very plainly dressed, although as Father’s daughter the fabric and cut of my clothing were excellent. I wore no jewelry and my hair was severely confined in a net that dulled its too-bright color.

After what felt like an eternity, the queen bade me rise and come closer. When I was near enough to smell the rosewater scent she favored, she reached out with one beringed hand to touch the small portion of my hair that the net did not cover.

“An uncommon shade,” the queen remarked. “Does it run in your family?”

“I do not know, Your Grace. But surely it is not all that rare.” Queen Kathryn also had red-gold hair, although it was darker than mine.

She smiled. “And yet, I think you do not much resemble Master Malte.”

I had always known that I did not look like Father or Bridget or Muriel. “My mother had dark brown eyes and my coloring,” I murmured.

“And the red hair? It is very like a shade I have seen . . . elsewhere.”

I wondered if she meant the princess or the king, but the full significance of what she was hinting at took longer than it should have to occur to me.

“I hope you will enjoy your stay in my household, young Audrey,” the queen said, dismissing me. “If there is aught that you need, you have only to ask one of my ladies.”

I backed away from her, as court protocol demands. It was only when I had retreated far enough to turn around that I realized how many people had observed our exchange.

The presence chamber was a large room used to receive important visitors as well as the ordinary ones like myself. The ladies, gentlewomen, and maids of honor who traveled with the queen on progress were all assembled there. There were men present, too—both members of the queen’s household and some of the king’s courtiers paying their respects. Dozens of pairs of eyes, their expressions ranging from curious to speculative to hostile, and none of them overtly friendly, bored into me. The queen’s reaction to my appearance and this intense interest from members of her household confused me. Then it made me think.

The color of my eyes and my skin tone came from my mother, but the red-gold hair—the shade that was so distinctively Tudor red—had no explanation unless I believed . . .

No! The idea was too preposterous!

But it would not go away. And it would explain so much, explain why I had been singled out to receive gifts and be given lessons.

I was a merry-begot. No one had ever made any secret of that. But Father said I was his child.

Could he have lied to me all these years?

There did not seem to be any other answer.

It was not impossible that King Henry should have fathered me. I knew he’d had at least one bastard, Henry FitzRoy, the boy he’d created Duke of Richmond and married to the Earl of Surrey’s sister. Richmond had died when he was only seventeen.

But if I was the king’s child, why not claim me? His Grace had given me to John Malte. Hidden me away.

Although I longed for solitude to gather my thoughts, I was obliged to remain in the queen’s presence chamber all the rest of that endless day. I did not even have Edith to offer solace. She’d been allowed to accompany me only as far as the outer chamber of the queen’s apartments. A few people spoke to me. I suppose I answered sensibly. Only one of them was anyone I knew by name.

Sir Richard Southwell came upon me as I stood in a window embrasure a little apart from the crowd of courtiers. He positioned himself in such a way that I could not move past him and escape.

“You will recall we met at Norfolk House, Mistress Audrey.” His voice matched his manner—obsequious and sly.

“I remember you, Sir Richard.” I had to fight the urge to cringe, for I also recollected the story Mary Shelton had told me. He had murdered a man. In sanctuary. It had amazed me at the time that such a one could remain so high in King Henry’s favor.

A traverse screened off part of that side of the room. I had sought greater privacy and now regretted my impulse. I was not afraid that Sir Richard would harm me physically, but just being so close to him made my skin crawl.

“The queen is not the first to . . . admire the color of your hair,” he said. “I noticed it the first time I saw you.”

I felt sick. He thought I was a royal bastard. And if he had seen the resemblance, perhaps others had, too. In my innocence, had I misunderstood the reason I’d been offered friendship by the Earl of Surrey’s circle? Had they cultivated me only because they thought I was connected to the king? Was that why Jack had taken me to Durham House in the first place?

Or was that why Jack had gone away? Had he feared to become entangled with me? More than one person with only a trace of royal blood had ended up in the Tower accused of treason. Any children born to them carried that same taint.

My head spun with possibilities, none of them palatable. How many courtiers, I wondered, had known of the king’s otherwise inexplicable fondness for his tailor’s illegitimate daughter? How long had they been speculating about my origins? Some would readily believe I was the king’s. Others would doubt. I desperately wanted to remain among the doubters.

“You must excuse me, Sir Richard,” I blurted, putting my hand to my mouth as if I were about to retch. “I am feeling ill.”

He backed up with alacrity and let me pass. I bolted from the presence chamber and did not stop running until I reached Father’s lodgings.

Father? Was he? I wanted to ask and did not dare. I did not want my growing suspicion confirmed. I pled a raging headache and took to my bed, but the next day I had to return to the queen’s apartments. One did not disobey a royal command.

At least Sir Richard did not reappear.

Soon after, the progress moved on, leaving Ashridge for Ampthill. I continued to spend my days loosely attached to the queen’s entourage, although she was often off hunting with the king. They were both mad for the sport.

I did not speak to Princess Elizabeth again, although I sometimes saw her from a distance. She saw me, too, although she never acknowledged me. I tried not to think about how much alike we looked.

Desperate for answers, I asked Edith bluntly why she’d been sent to me. She seemed surprised by the question.

“It was the king’s wish.”

“But why favor me? I am naught but a merchant’s daughter. You were trained to serve the nobility.”

It amazed me that I had never before considered this odd. I’d simply accepted Edith, as I’d accepted the tutors and the gift of a little dog—one of the king’s own dogs!

Edith frowned. “No one ever said.”

“But you must have speculated.”

My pleading look weakened her resolve. “A guess only. That perhaps you were . . . kin to someone important. I never heard who your mother was.”

“A laundress. That’s all. A servant far lower than you are yourself.”

“Then if not your mother . . .” Her voice trailed off and her eyes widened. Suddenly, she was afraid. “It is not for me to say more. Ask Master Malte if you have questions.”

“Does my father pay your wages?”

She would not meet my eyes. “I have a stipend from the Crown,” she whispered.

I quailed at confronting Father with my suspicions. I needed to know the truth, but to ask if the king had fathered me would be to accuse John Malte of lying. I was loath to do such a thing. I told myself that my resemblance to the princess was pure chance. And we’d most certainly had different mothers. Why, then, should I suppose that our father was the same man?

We were still at Ampthill when, unexpectedly, Princess Elizabeth was sent back to Ashridge, where Prince Edward had remained when the court moved on. No one seemed to know why, but the king was said to be furious with his youngest daughter.

“I expect she asked an impertinent question,” Father said when I asked him about Her Grace’s sudden departure. “Childish curiosity is natural, but sometimes it has unforeseen consequences.”

“A question about what?” I persisted, fearing his answer but feeling driven to ask.

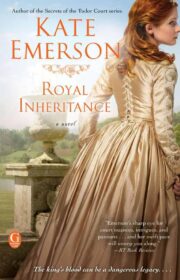

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.