Jack stayed the night, helping to guard our house. He and Father and the apprentices took shifts keeping watch. I saw him again when we broke our fast. Over bread and ale, he managed a smile for me, but his face was haggard and his usual cheerful disposition was nowhere to be found.

“You were right,” I told him. “The Earl of Surrey would not be a suitable patron for you. Likely you’d end up in gaol if you entered his service!”

“I have been thinking of speaking to Sir Thomas Seymour about a post,” he said.

I felt both my eyebrows rise at the name. I had never met Sir Thomas, younger brother of the late Queen Jane, but I knew that the Seymours and the Howards were rivals for power at court.

“Sir Thomas has recently returned to England from a mission abroad,” Jack added, “but rumor has it that he’s to be appointed ambassador to the regent of the Netherlands.”

My heart sank at this news. I was not sure exactly where the Netherlands were, but I knew they were far away from Watling Street. What Jack was really saying was that he was not just planning to leave the Chapel Royal. He was planning to leave the country.

And me.

For days after the earl and his minions went on their rampage, that was all anyone in London talked about. Watling Street had not, after all, been in the path of the destruction. After attacking Sir Richard Gresham’s house, the rioters had gone in the other direction, shooting their strongbows at apprentices in Cheapside, then moving on into the Poultry and through the Stocks Market. After that they’d headed east along Lombard Street into Fenchurch Street, stopping there long enough to break all the windows in an alderman’s house. They damaged other merchants’ property along the way, and even shattered the glass windows in some churches, before jumping into boats and crossing the Thames to Bankside to shoot stones at the whores there until nearly two in the morning.

Surrey was soon back in the Fleet thanks to this escapade, along with his squire, Tom Clere. Two of their fellow rioters, Thomas Wyatt the Younger and William Pickering, ended up in the Tower of London for their part in the vandalism.

Young men capable of fighting in the king’s wars do not stay locked up for long. Surrey was free by mid-May and the others soon after. By then, Jack was in Brussels with Sir Thomas Seymour and my music lessons were a thing of the past.

“Poor Audrey,” Bridget said, taunting me. “You have lost all your new friends!”

I feared she had the right of it. It had been a long time since I’d heard from Mary Shelton. I felt very sorry for myself.

I reached the age of fifteen in June of that year. As each of my sisters achieved that milestone, Father had begun negotiating marriages for them. I would be no different. By the time I was seventeen or eighteen, I would be wed, and not to Jack Harington. Father would look for a match where he always did, within the community of merchant tailors in London. That was why Bridget was about to become betrothed to our neighbor, John Scutt—a man old enough to be her grandfather.

She said she did not mind in the least. He was very wealthy.

19

Ashridge, August 1543

The palace of Ashridge in Hertfordshire is a goodly complex complete with its own church and a cloister. It sits on high ground, surrounded by woods and hunting forests. Father was assigned to a double lodging—two rooms with a fireplace and a private privy—in the palace itself.

“This is a mark of the king’s favor,” he told me. “With so many royals and their attendants in residence, even some of the ladies and gentlemen in waiting had to be billeted in nearby villages and manor houses.”

“No doubt King Henry wants you near at hand for fittings.”

I sent Edith to see if a meal could be had. Peter stayed behind to put away Father’s clothing and arrange his comb, brush, and toothpick on a table.

We had traveled to Ashridge on horseback. This had been a new experience for me, but not one I much enjoyed. Although the pillion attached to the back of Father’s saddle was padded, it was still very hard, and I was obliged to sit in an awkward position in order to keep hold of his waist. I was fearful that if I let go, even for an instant, I would fall off the horse.

The journey had taken three days. It had seemed to me that we were traveling at a snail’s pace, until Father told me that to make the same trip in comfort, carried in a litter, would require five interminable days on the road. Our speed had been set by the two wagons filled with fabrics and trimmings that accompanied us. Edith and Peter, and Pocket, had been obliged to ride stuffed into the corners in one of them.

The king sent a contingent of royal guards to escort our little convoy through the countryside, but that was more to protect our cargo than for our safety. At Ashridge, Father would turn the cloth in the wagons into garments for the king, his new queen, and his three children.

In mid-July, His Grace had married his sixth wife, a widowed gentlewoman named Kathryn Parr. Soon after, I had been invited to join the king’s annual progress. Or rather, Father had been sent for and was instructed to bring me along.

It had been a strange experience for me to ride past all those open fields and to travel miles at a time without passing more than a handful of small, squat buildings. I was accustomed to London, where the town houses rose to three and even four stories and were crammed in so closely that only narrow alleyways could pass between them.

I’d had little opportunity to question Father as we traveled, since he would have had to crane his neck to speak to me. On each night on the road, I’d been so tired that my only thought had been to seek my bed. We’d stayed in courtiers’ houses, but the courtiers had not been at home. Edith and I and Pocket had supped alone and retired early. Now, for the first time since leaving London, I took a good hard look at Father. His face was creased into a worried frown.

“What is it that troubles you, Father?” I asked. “Do you fear for Mother Anne and Bridget and Muriel and Elizabeth and the baby?” We’d left them all back in London, where this unusually wet summer had been punctuated by outbreaks of the plague. “Surely there is no greater danger there than there is in any other year.”

“The plague is always with us,” Father said. “It is God’s will who lives and who dies.”

I nodded. That is what we were taught and I did believe it. But I also knew that those who owned country houses regularly fled the city in the hope of avoiding contagion.

“Why was I singled out to come with you, and not the others?” I asked.

“It is not your place, nor mine, to guess at the king’s reasons, Audrey. And you are not to trouble anyone with impertinent questions while you are part of the royal progress.”

“Yes, Father.” I agreed with suitable meekness, but my curiosity was far from quelled.

All three of the king’s children were at Ashridge because the new queen sought to reunite them with their father and end the estrangement between His Grace and his two daughters, one by Catherine of Aragon and one by Anne Boleyn. Princess Mary, the eldest, was then twenty-seven years old, while Princess Elizabeth had nearly reached the tenth anniversary of her birth. Their brother, Prince Edward, nephew to Sir Thomas Seymour, was not yet six. He had been born in the month of October.

It was the young prince I encountered first. Father was ordered to go to his rooms to measure him for a new doublet. He took me along, although my presence garnered outraged looks from most of the all-male household. One or two of the gentlemen just looked amused.

“Speak to no one,” Father cautioned me. “If you are very quiet, they will lose interest in you. The prince is allowed visits from other children, both boys and girls. Remember that and ignore rude stares.”

I thought about reminding him that, at fifteen, I was no longer a child, but I decided against it. Who would not want the opportunity to meet a prince?

At first I did not find it difficult to heed Father’s warning. The magnificence of my surroundings struck me dumb. I thought I had seen richly furnished chambers at Whitehall and Greenwich, but the prince’s lodgings at Ashridge were more spectacular still. Every room was hung with Flemish tapestries depicting classical and biblical scenes. The prince’s plate and cutlery, set out on sideboards, sparkled with precious stones. Even the cloths he used to wipe his fingers after meals were garnished with gold and silver.

In the prince’s presence chamber it was a stack of books that caught my eye. The fact of them alone was impressive, for printed books were rare and expensive. These volumes could only belong to royalty. One had a cover of enameled gold. The clasp was a ruby. Others were decorated with crosses or fleurs-de-lis or roses made out of diamonds and other precious stones.

Prince Edward himself was a small, slight boy with fair skin and hair the color of ripe corn. At first glance, with his pink cheeks and pale complexion, he looked like an angel. Closer scrutiny revealed a pointed chin and tightly pursed lips. He did not like being told to stand on a stool and hold still while Father took his measurements. When Father turned away, the prince made a face at him.

This sign of disrespect angered me. I stepped closer, hands fisted on my hips, and glared upward, daring to meet his eyes. They were a very pale gray in color and widened at my boldness. Had he not been up on that stool, I would have towered over him.

“If you do not wish to have new clothes, you have only to say so,” I hissed at him. When Father cast an appalled look my way, I hastily added, “Your Grace.”

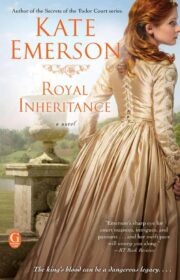

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.