He took a far greater interest in Bridget’s more obvious charms. My breasts were saucepans. Hers were stew pots. She encouraged him, too, doubtless to spite me, for she had already set her sights on someone far wealthier than Jack Harington.

Self-absorbed as I was in private pleasures and frustrations, I was only dimly aware of a heightened tension affecting both the city and the court. It was an exceeding hot summer with no rain. There was drought. Men feared the return of the plague. Although that devastating sickness did not come upon us, at least not that year, there were outbreaks of another sort. Short tempers led to fights. Some became near riots. After the court went on progress during August, September, and October, thankfully without a full contingent from the Chapel Royal, rumors drifted back to London that the king was in failing health.

These proved unfounded, God be praised, but His Grace chose to remain at some distance from London until mid-December. Most of the courtiers who were not attached to the so-called riding household took themselves off to their country estates. The Duchess of Richmond left for Kenninghall in Norfolk, taking Mary Shelton with her. There was no mention of adding me to her household.

13

Norfolk House, January 1541

I waited until after Epiphany to pay a visit to Norfolk House, although the duchess had spent Yuletide there. I brought Pocket with me, since he was easy to carry and got along well with my Lady of Richmond’s spaniels. All the dogs avoided Mary Shelton’s cat.

The Earl of Surrey and some of his followers were in his sister’s rooms when I arrived. Surrey looked at Pocket askance, not having seen him before.

“That is a glove beagle,” he remarked, “not the usual sort of lapdog.”

“He was a gift, my lord.” The slight sneer on Surrey’s face prompted me to add, “From the king.”

One auburn eyebrow lifted and he darted a questioning glance at the duchess. She ignored him. I tucked Pocket away, out of sight, uncomfortably aware of the earl’s scrutiny and that of a member of his entourage, a fellow I had not noticed before.

He was the oldest person present, by at least a decade, and, by his dress, of lower birth and status than the earl. His mouth turned down while his nose stayed up in the air, as if to avoid smelling something unpleasant. He was clean-shaven, a poor choice since it revealed a weak chin.

“Have you heard about Anne of Cleves’s visit to court over Yuletide?” Mary Shelton asked, glancing up from her needlework. With a gesture, she invited me to sit beside her and join in the task of hemming what appeared to be an altar cloth.

I was glad of the excuse to move farther away from the stranger, who was now whispering in a servant’s ear. The lad scurried away as if he feared a beating if he did not make haste. I thought perhaps he had reason.

“I heard that the former queen was installed at Richmond Palace,” I said to Mary. King Henry had given it to her in return for her agreement to annul their marriage.

“She’s hardly a prisoner there! In any case, she arrived at the gates of Hampton Court on the third of January, two days after the traditional exchange of gifts on New Year’s Day.”

“You make it seem as if she was not expected.” Surrey sounded disgusted by the subterfuge. “The entire production was carefully staged.” He helped himself to a goblet of wine and drank deeply.

“No doubt it was.” His sister kept her eyes on the intricate stitches she was using to attach a piece of black-work lace to a kirtle. “But it was a splendid spectacle all the same. You’d have enjoyed it, Audrey. Lady Anne of Cleves, who now must call herself the king’s sister where once she was his wife, threw herself to her knees before Queen Catherine like the most common suitor. Then the king arrived on the scene—just in time to witness this touching tableau. He raised Lady Anne up and kissed her and embraced her and then they all sat down to sup like three old friends.”

“Has Anne of Cleves finally learned enough English to converse properly?” I asked. Her difficulties with the language had been widely reported.

Lady Richmond laughed. “So it would seem. But the highlight of the evening came after the king retired to his own apartments. Catherine called for music and then the two ladies danced together, whiling away the rest of the evening in that manner.”

“A display of perfect amity.” Scorn laced Surrey’s words.

“Why are you so wroth with Cousin Catherine?” the duchess asked. “It is to our benefit to have a kinswoman in the king’s bed.”

Seated beside Mary on her bench, I felt as well as saw her wince. “Is aught wrong?” I whispered.

Mary, blunt as ever, gave me a frank answer. “A momentary pang, I assure you. Having a kinswoman in the king’s bed is not always comfortable for the rest of the family. You see, during Anne Boleyn’s tenure as queen, she ordered her kinswoman, my sister Margaret, to allow the king to seduce her. The queen hoped to distract His Grace from lavishing his favors on another young gentlewoman at court.”

She kept her voice low, but the same gentleman who had earlier been so rudely staring at me cocked his head in our direction, blatantly eavesdropping on our exchange. Tom Clere, who was also close enough to overhear, leaned past me to give Mary a quick peck on the cheek. As he did so, I caught a whiff of bay leaves.

“Here you have the only woman in England who would not think it an honor to be the king’s mistress,” he said with a chuckle.

Mary swatted at him, missing when he ducked and nearly striking me. “Terrible man!” She sent me an apologetic look and sighed. “The truth is that people often confuse me with my sister. It is most annoying.”

“Better that than to be mistaken for your namesake the nun,” Clere teased her.

“Former nun,” Mary muttered through gritted teeth. There were neither nuns nor monks in England anymore, not since King Henry dissolved all the religious houses.

Clere, unrepentant, wandered off. I realized, with a sense of surprise, that the duchess and her brother were still talking about Lady Anne’s visit to court. The exchange between Mary and Tom Clere had passed unnoticed by anyone but myself and the stranger.

“After dinner the next day,” Lady Richmond said, “well pleased with his new bride, the king presented her with a ring and two lapdogs. The queen, to show favor to her guest, promptly offered all three to Lady Anne, who accepted them most graciously.”

“Did the queen not fear to offend His Grace by giving his gifts away?” The question burst out of me before I could stop it. I stammered an attempt at an explanation: “I . . . I would never give Pocket to someone else.”

Surrey laughed. “No, indeed. The king would not be pleased to hear of it if one of his glove beagles were to go to another. I am surprised he parted with that one. But these dogs were just ordinary spaniels, like that lazy beast.” He sent a contemptuous look in the direction of one of his sister’s lapdogs. Curled up close to the hearth, it was snoring gustily.

“I suspect they had arranged it all between them beforehand,” the duchess said, “for the king was quick to make a gift of his own to his former wife—an annuity of a thousand ducats.”

My eyes widened at the magnificence of this sum. King Henry must have been very grateful indeed to Anne of Cleves for allowing him to put her aside without protest.

“Lady Anne’s gift to the king,” Lady Richmond continued, “was also very fine—two splendid horses caparisoned in purple velvet.”

I scarce heard her. That man was watching me again. He had an intense, disconcerting gaze. His heavy-lidded eyes shifted as I moved, leaving me with the uneasy feeling that he had some special reason for wanting to examine me so closely. Unable to imagine what it was, I fixed my attention on my stitches and attempted to ignore him, but I found no true relief until the earl and his gentlemen took their leave of us.

“Who was that older man?” I asked. “The one who stared at me so boldly.”

“Sir Richard Southwell.” Mary’s lips pursed as she spoke his name, as if saying it left a bad taste in her mouth.

“He is one of my father’s retainers,” the Duchess of Richmond said.

I looked from one woman to the other, puzzled by their reticence. Only the strength of my own reaction to the man persuaded me to pursue the matter. “Neither of you cares for the fellow. What has he done to make you so dislike him?”

Mary’s derisive snort spoke volumes, but did not clarify matters for me.

“What has he not done?” The Duchess of Richmond made a moue of distaste. “Some seven or eight years ago, he and several accomplices pursued a man into sanctuary at Westminster and slew him.”

I gasped. Murder was a heinous crime, but to violate sanctuary made it a hundred times worse.

“There was no doubt of his guilt,” Lady Richmond continued, “but my father the duke did not wish to do without his services. He persuaded the king to grant Sir Richard a pardon. The villain was fined a thousand pounds, but he kept his life, his property, and his freedom.”

“And he did not even have to pay the entire fine,” Mary put in. “He gave the king two of his manors in Essex to make up the difference, and after that it was as if nothing untoward had ever happened. He has been at court ever since, regularly collecting honors and new grants of land.”

“Why was he so interested in me?” I asked.

“No doubt because you are new to our circle,” the duchess said.

Mary snorted. “Say rather because she is young and innocent of the ways of men. And her looks are . . . pleasing.”

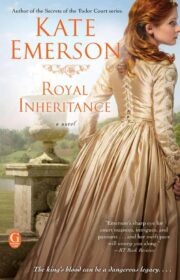

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.