Boisterous and full of good cheer, Surrey slapped one of his fellows on the back and embraced another. I could make out little of his appearance from my perch, only a full head of auburn hair and a rather scraggly beard of the same color.

The official festivities ended when the king and queen departed. The rest of the company began to disperse as well. When Jack led me out of the musicians’ gallery, I expected to return to the water gate, but the passageway he chose took us instead into an antechamber containing another narrow flight of stairs. Edith and I followed Jack up, and up, and up, until the steps ended in a little turret room. Its windows looked down into and out over the Thames.

“You should not be here with him,” Edith hissed at me, alarmed by the remoteness and privacy of the chamber.

“I am in no danger,” I whispered back. In truth, I wished there were some hope that Jack Harington might look upon me as a young woman he’d like to steal away and marry. I adored my music master, but he still looked upon me as a child. That I was a child—not quite twelve years old—was something I preferred to ignore.

“Put aside your foolish daydreams,” Edith snapped. “That young gentleman is up to no good.”

Jack was, in fact, arranging cushions on the floor and setting out beakers and cups.

Edith was still trying to push me toward the door when two very finely dressed courtiers entered through it.

“Jack!” the man exclaimed. “Well met! And this must be the lass they call ‘Harington’s pet.’ ” He looked straight at me when he said it, a friendly smile on his darkly tanned face.

“Tom! Mind your manners!” His female companion smacked his forearm with a closed fan, but she was laughing.

Edith bent to speak into my ear. “That fellow is Thomas Clere, squire to the Earl of Surrey.”

Overhearing, the young man’s head snapped around and he gave my maidservant a frosty stare. It faded as quickly as it had appeared. “Edith, by my spurs! We wondered where you had vanished to.”

He might have said more, had not the Earl of Surrey himself arrived just then. The woman with him was not his wife. She was his sister, the Duchess of Richmond. Without standing on ceremony, they settled themselves on the cushions Jack had arranged. Master Clere and the other woman joined them.

I glanced at Jack, who remained standing, uncertain how to act. Was this the “surprise” he had promised me? I could not imagine why he would think I’d wish to meet these people, but when he seized my hand and thrust me forward, I went. With a flourish, he presented me to the earl and the duchess first and then to the gentlewoman who had come with Thomas Clere, Mistress Mary Shelton, companion to the duchess.

Up close, I saw that the earl and his sister shared that auburn hair. Both had hazel eyes, but while her fair coloring was untouched by the sun, his skin had a weathered look. Both he and his squire, I surmised, spent many hours out of doors, hunting, hawking, and riding.

Mistress Shelton’s face was not as full as the duchess’s and her nose was longer and more tapering, but she shared that pale complexion. Along with Master Clere, they were all of an age, and it was nearly twice my years. I managed a curtsey and a mumbled greeting, but apart from that I found myself tongue-tied. This was very grand company indeed for a merchant tailor’s daughter.

Several others soon joined us. I cannot now recall which members of the earl’s circle they were. Surrey often held impromptu musical and literary gatherings. Some of those who attended never came again. Others were part of an intimate group always in attendance on the earl or on his sister.

At first the talk was all of the tournament.

“M’lord Surrey was magnificent.” Mistress Shelton addressed this remark to me in a friendly fashion, attempting to draw me out. Edith had retreated to a corner, effacing herself as any good servant must when in the presence of her betters. “He rode onto the field behind an exquisite float depicting the Roman goddess of arms. His pennant and shield had a silver lion emblazoned upon them and other Howard emblems were embroidered all over his white velvet coat.”

“My father may have made that coat,” I ventured, trying to overcome my shyness around these glittering strangers. If Jack was comfortable with them, so should I be.

“Your father?” Confusion had her brow furrowing.

“Master Malte, the royal tailor.” There was no apology in my voice. I was proud of Father’s work.

She gave me a peculiar look, but if she thought I should go join Edith in the corner, she was kind enough not to say so.

By then, the general conversation had turned away from jousting onto poetry. An earnest young woman begged the Earl of Surrey to recite some of his verses.

He stood and declaimed:

Give place, you lovers here before,

that spent your boasts and brags in vain:

my lady’s beauty passeth more the best of yours,

I dare well sayn,

than doth the sun, the candle light,

or brightest day, the darkest night.

“Mary is working on a new poem,” Lady Richmond announced, nudging Mistress Shelton.

“It is not yet ready to be heard,” Mary Shelton protested.

“Let us judge that.” Thomas Clere slung a familiar arm around her shoulders and planted a smacking kiss on her cheek.

She pushed him away, and none too gently, but after a moment she closed her eyes and recited:

And thus be thus

ye may assure yourself of me.

No thing shall make me to deny

that I have promised thee.

“It needs work,” Surrey said.

“It is the worst sort of doggerel,” Mistress Shelton admitted in a rueful voice. “I am a better copyist than I am a poet.”

Jack Harington cleared his throat. “I wish to present to this company a new poet.”

I looked at him expectantly, and then in slowly dawning horror as I realized I was the one he meant. “Oh, I cannot. My verses have no more merit than an amateur artist’s sketches.”

Thanks to Jack’s lessons, I had discovered talents I’d never dreamed I possessed. Not only had I shown an affinity for playing the lute and for singing, but I also had begun to develop the knack of setting words to music. Encouraged by my tutor, I’d tried my hand at composing my own verses, but they were poor, pitiful things.

“Come, Mistress Malte,” Mary Shelton urged me. “Your attempt can be no worse than mine and we are all friends here, united in our poor efforts to emulate the great poets of antiquity.”

“My efforts are worse than poor and were intended only to be set to music.”

“There is nothing ignoble about writing lyrics,” Lady Richmond said. “Why, the king himself wrote the words to ‘Pastime with Good Company’ and many of Sir Thomas Wyatt’s verses have been set to music.”

“Thomas Wyatt the Elder,” Surrey clarified. I gathered from this that the poet had a son by the same name, but at the time I had never heard of either of them.

“Wyatt is greatly to be admired,” Tom Clere said, “if only for keeping his head.”

Nervous laughter greeted this remark.

“I do not understand,” I whispered to Mary Shelton.

Mistress Shelton’s shoulders tensed. Her lips flattened into a thin, tight line. I learned much later that she had once been courted by Sir Thomas Wyatt the Elder and that he’d written poems to her, even though he’d had both a wife and a mistress at the time. Still, she was, as I was to learn, the most blunt-spoken of that company and was nothing loath to fill in the gaps in my knowledge.

“Sir Thomas Wyatt, when a young man, was in love with Anne Boleyn . . . before she married the king. He might easily have gone to the block, accused of having been one of her lovers. Together with my sister, Margaret, one of the queen’s maids of honor, I was at court to witness these events. I truly believe that it was one of Wyatt’s poems that saved his life, for King Henry took it as proof that the poet never meddled with the queen.”

“Whoso list to hunt, I put him out of doubt; As well as I may spend his time in vain!” the Earl of Surrey recited in a low voice. “And graven with diamonds in letters plain there is written her fair neck round about, Noli me tangere, for Caesar’s I am, and wild for to hold, though I seem tame. ”

“Noli me tangere?” I was ignorant of foreign languages. “What does that mean?”

“Do not touch me,” Mary Shelton translated. “And Caesar was meant to be the king. Now you, Audrey. Share something you have written.”

I knew I did not approach within a mile of Sir Thomas Wyatt’s poetic talent. I doubted I even reached the heights of Mary Shelton’s “doggerel.” But I was emboldened by her encouraging smile.

Because I was not accustomed to reciting verses in a normal speaking voice, I sang the words:

The linnet in the window sings despite her cage

when other creatures would rail and rage.

And I, beside that same window, do peruse my page

and wait for the one who’ll free me when I come of age.

I faltered into silence. An unnerving pause followed.

“Clever,” the Earl of Surrey conceded. “Although you would do better to follow Petrarch’s model and write a sonnet.”

As if the rest of the company had only been waiting for the approval of the highest-ranking person in the chamber, they all chimed in with words of praise and helpful hints for improving my verses. For the most part, the criticism was kindly meant. More remarkable still, in spite of my youth and my inferior station in life, they treated me as an equal.

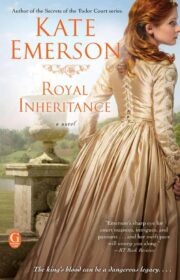

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.