“I beg your pardon, Your Majesty, for causing so much trouble.”

“It is easy to forgive a pretty girl,” the king said. “Now tell me, Audrey, what was that song you were singing?”

“I do not know its title, Your Grace.”

“Mayhap I should ask you, then, where you learned it.”

“In the chapel, Your Grace.” I hesitated, then decided it would be best if I confessed the full extent of my transgressions. “I go there sometimes, to listen to the choristers rehearse. They make very fine music,” I added in an earnest voice.

“And you have a very fine voice, but that particular hymn is perhaps not the best choice for a girl of your years. It is called ‘Black Sanctus, or the monk’s hymn to Satan.’ Did you know that?”

“No, Your Grace,” I whispered. “I am exceeding sorry. I will never sing it again.” I wished I could crawl into a hole and vanish. I was certain that anything to do with the devil must be very bad indeed.

The king studied me for a long moment, making me tremble inside. He had been quick to go from anger to good humor. I feared he could return to the former emotion just as fast.

“You must have lessons,” he announced, taking me by surprise. “A singing master. I will send young Harington to you, the very lad who wrote both the words and the music to that song you were singing. You have good taste in music, Audrey. I often sing that one myself, for it is a cleverly written antimonastic hymn.” He laughed at this last comment and all his minions laughed with him.

I did not understand the reason for their amusement, but I stammered my thanks. I was elated by the news that I was to have lessons. To be taught the proper way to sing seemed the most wonderful boon anyone could grant me, even better than the king’s earlier gift, my dear companion, Pocket.

“We are most grateful, Your Grace.” Father echoed my sentiments, sounding sincere, but I could not help but notice that his brow was deeply furrowed. Something worried him about the idea.

“She shall have a dancing master, too,” the king declared. “It will do no harm for her to learn all the courtly arts. Do you know how to read, Audrey?”

“A little,” I said, bolder now. “And I can write a bit, too. And cipher.”

Father placed one hand on my shoulder and waited until the king shifted his gaze from me to him. “Those are skills customarily taught to the children of merchants, Your Grace, even the girls. A young wife must be able to keep her own accounts. How else should she know when she is being cheated by the butcher?”

Unspoken was the obvious thought that such a one had no need to learn how to tread a stately measure.

The big vein in His Grace’s neck throbbed. He expected unquestioning obedience from his subjects. While polite, Father’s defiance rankled.

I burst into speech, hoping to avert trouble. “I will be a very good student. When I learned to cipher, my teacher said I was quick with my numbers.”

Distracted, King Henry inquired further into what instruction I had been given. Satisfied that it was adequate, His Grace was about to depart when he remembered Mistress Yerdeley and recalled that her inattention had left me free to wander about the palace alone.

“We will also find a reliable woman servant to wait upon you,” the king decreed. “One vigilant enough not to let you out of her sight when you visit our court.”

8

December 1539

Think you’re a fine lady, do you?” Bridget’s taunt was delivered in a whisper but it stung nevertheless.

“I am the same as you.” I kept my head bent. Pocket, who lay curled up in my lap, licked my fingers.

“Then why does Father pay for lessons for you and not for the rest of us?”

“It is not Father who hired him,” I muttered, refusing to so much as glance at the cadaverous figure hovering near the doorway in deep discussion with Mother Anne. Afflicted with the improbable name of Dionysus Petre, he had introduced himself as my dancing master. His arrival at the house in Watling Street a short time ago had thrown the entire household into an uproar, but it was his flat refusal to teach anyone but me that had provoked my sister’s ire.

“What do you mean?” she demanded. “Who else would be so generous? Besides, we all know you are Father’s favorite.”

“I am not!” Although I denied her claim, I thought she might have the right of it, but simple common sense prevented me from boasting of such a thing. “And it is the king who pays.”

The angry expression on her face changed to one of disbelief.

“Ask him.”

Hearing the agitation in my voice and seeing me gesture in his direction, Master Petre gave a start. The sight of Bridget, fire in her eyes, stalking in his direction, had him stammering an apology, although what reason he should have to beg her forgiveness eluded me.

Bridget came to a halt a mere foot in front of him, her stance wide and her hands on her hips. “Is she telling the truth? Does King Henry employ you?”

“I cannot say, young mistress.” The poor man squeaked like a terrified mouse. In an attempt to avoid meeting her eyes, his gaze dropped lower, landing on her bosom. That seemed to fluster him even more.

“Cannot or will not?” Bridget took a step closer.

Her prey threw both arms up in front of his face and backed away, nearly tumbling down the stairs that led to the shop in his attempt to escape.

I felt sorry for the dancing master. He was twice Bridget’s age and no doubt the younger son of a gentle but impoverished family, forced to earn his living by giving lessons. Even more than an artificer like Father, he had, of necessity, to bend his will to that of his clients.

“Bridget, leave him be.” I set Pocket on the floor, crossed the room, and positioned myself between my sister and the dancing master. “I have already told you that it is King Henry who pays him.”

“First a dog. Now a dancing master. Why should you be so favored?” Bridget turned the full force of her outrage on me, giving Master Petre time to recover his wits. “It is not fair. I am older than you are.”

“And Elizabeth is older than us both. Perhaps Master Petre should give her lessons instead.”

“Oh!” he exclaimed. “I cannot—” He broke off, eyes wide, when we both turned to glare at him.

It was perhaps fortunate that Elizabeth and Muriel entered through the other door at that moment. They had been to the fishmongers and Elizabeth still carried her shopping basket.

“Whatever is going on?” she asked. “We could hear raised voices all the way to Master Scutt’s house.”

Mother Anne, who was inclined to let Bridget have her way, now stepped in. “It will not do to have the entire neighborhood privy to our business. You will say no more, Bridget.”

With a snarl, Bridget whirled around and stalked to the window that overlooked the street. From that vantage point she had a fine view of the back of the Cordwainers’ Hall, but I doubted she saw it. All her thoughts were turned inward. A visible tremor made her entire body vibrate as she seethed with frustration.

“Master Petre,” Mother Anne said in the firm voice she used to correct the servants and apprentices, “I believe a compromise is in order.”

She drew him deeper into the room and settled him in the Glastonbury chair that was Father’s favorite. Marking his flushed face and continued inability to string more than two words together at a time, she called for Ticey, another of the maids, and sent her to the kitchen for a soothing posset.

Slowly, Master Petre regained his composure. After he had drained the goblet Ticey brought him—steeped chamomile with a few other herbs mixed in—Mother Anne informed him that he would be teaching all the daughters of the house.

By that time, he had lost the will to argue.

When my tiring maid arrived later that same day, Bridget’s wrath found a new target. Her name was Edith Barnard, a plump young woman who looked down her nose at the other servants in the household, especially Lucy.

“You will also serve me,” Bridget informed her.

Edith regarded my sister through heavy-lidded eyes that were most effective at hiding her thoughts, but she made no effort to adjust her implacable attitude. “I am here to serve Mistress Audrey,” she said, and thereafter ignored Bridget as if she had no more substance than an annoying bug.

A quarter of an hour of such treatment and Bridget, fuming, went away. I heard her flounce down the stairs to the tailor shop. With any luck, flirting with the apprentices would put her in a better mood.

“Your bedchamber is passing small,” Edith said when we were alone. She had already begun to reorganize my belongings, separating them from my sisters’ possessions.

Light on her feet, Edith moved with an efficiency and sense of purpose I could not help but admire. At the same time, I found her self-confidence daunting. I had never met a maidservant who put on such airs, and it was not as if she had obvious cause to think so well of herself. She was no more than twenty years old and was afflicted with a splotchy complexion.

“Lucy, poor thing, is slow-witted,” I ventured as Edith inspected my shifts and folded each one neatly before tucking it into a drawer in the wardrobe chest. I sat atop another of the storage chests we used for clothing, with Pocket once again nestled on my lap. It soothed me to stroke his soft fur. “We are obliged to repeat orders two or three times before she understands what it is we want. It would be a great help if you could assist her in her duties. My sisters—”

“Indeed, I cannot, Mistress Audrey. I have been sent here to serve you and you alone.”

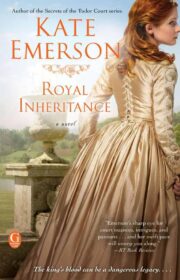

"Royal Inheritance" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Royal Inheritance". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Royal Inheritance" друзьям в соцсетях.