Cami would be a hostage the minute she stepped out onto the pavement. No comfort to know she’d be armed.

“Or they’re leaning out the windows trying to get themselves shot.” Hawker had helped himself to a handful of gravel a few streets back, stealing it out of a potted plant on somebody’s front steps. He’d been shying it, stone by stone, into the street as they walked along, hearing it skip and clatter, watching it when there was light enough from some lamp in a window. “I don’t know why they do that. If you asked a hundred citizens of London, ‘What should you do when people start shooting off guns?’ not one of them would say, ‘Go stand at the window and pretend to be a pheasant.’”

The last house they passed was a tavern with a light at the door and noise inside, even at midnight. The inns and public houses were busy all night at the docks, working to the change of the tides instead of the time of day.

The dock was dark, the uneven succession of long planks treacherous underfoot. Down at the end, an open boat was being loaded by three men under the light of a single lantern. Baskets of bread, more baskets—those might be eggs—and what looked like milk cans. The pile to the right was probably his luggage.

On the Thames, every ship on the water was slung with lanterns to keep thieves at bay. Light repeated in the water, rippling, broken into pieces. The Pretty Mary was one of those ships.

Doyle said, “You could just go to Italy and simplify matters immensely. I hear the light’s good for artists.”

“It’s good light.”

“I’m not new at this business. I’ll take the Merchant for you.” Doyle was in outline against the river. “I’ll take him alive because we need him for questioning. But he will die. It’s just a squabble over who gets to kill him.”

“He’s worried about the woman,” Hawker said.

“I know that.” Doyle watched the loading at the end of the dock. “We all know she’s walking into a trap. Whether she lives depends on what the Merchant wants and whether we can get to her in time.” He turned back. “When she walks onto Semple Street, I have as good a chance of keeping her alive as you do.”

Hawk said, “He’s not listening. He’s thinking about taking a dive into that dirty river when he’s about halfway between here and that boat out there.”

“Ship,” Doyle corrected. “The big ones are ships. The small ones are boats. Pax, I can’t promise to keep her alive or get her safe out of England. I can’t promise to keep her out of prison. She’s a spy and I don’t know what she’s done—”

“The difference is, he doesn’t care what she’s done,” Hawk said.

“But if it’s possible, I’ll keep her alive and loose on the streets,” Doyle said. “I have influence and I’ll use it for her. Will you go to Italy and spy on the French and Austrians and leave her to me?”

They already knew his answer. He gave it anyway. “No.”

“You’re disobeying direct orders. You know that.”

“I don’t have any choice.”

Waves slapped the mud under the dock. A metallic cold rose up from the expanse of water. Even if these two didn’t force the issue, even if they let him walk away, he knew he’d be walking away from the Service.

“I hope you’re not expecting me to tie him up and haul him out to that ship.” Hawker still had a few pieces of gravel held in reserve. He skidded one out across the water and listened to it splash. “He’d stab me, being in thrall to that devil bitch of his.”

Might as well make it clear. “There are two of you. I can’t win without hurting you. And I’ll fight. I don’t think you’re willing to hurt me.”

“We’re not going to do it that way,” Doyle said.

“Good.” Hawk threw his last piece of gravel and waited for a splash. “Because I’m bloody well not pulling a knife on Pax. Last time I did he almost gutted me.”

“I sliced your forearm. One cut,” he said.

“It is only by my supernatural agility that I escaped that encounter alive. Now I’m going to wander down the nearest alley to relieve myself against a wall, leaving Pax to disappear into the cool of the evening or take ship to Italy, whichever strikes his fancy. Mr. Doyle, if you want to stand between Pax and his murderous woman, I leave you to it.”

A dark chuckle. Doyle said, “I’m not that stupid.”

Hawker became silence and darkness, walking away.

Galba sent Doyle and Adrian to put him on the ship because he knew they wouldn’t force the issue. Galba had left him the choice—obey or disobey—and all the consequences.

He called, “Hawk.” He felt, rather than saw or heard, Hawker pause.

“Hmm?”

“I’ll be at the Baldoni’s, off and on, starting in the morning. It’s not my operation—”

“It’s your operation,” Doyle said. “I’ll send Hawker over about noon. Tell him what you need from the Service and I’ll see you have it.” He paused. “You will get me the Merchant. He killed an old friend of mine.”

It was like flame, the unwavering, burning cold inside him. “I will bring him down.”

Hawk had become invisible. The trailing edge of his voice drifted back. “Galba’s going to kill me for this.”

Doyle aimed his reply in that direction. “Cheer up, lad. Likely somebody’ll beat him to it.”

Forty

With a small decision, we change all the future.

The road back to Cami felt familiar, even though he’d only walked it twice now. It was all in the anticipation.

At the end, almost there, Pax went motionless in the dark at the doorway next to the Baldoni house. Men approached behind him on the street, walking without reservation or wariness. Two . . . three of them.

He breathed shallowly. He was too old a hand to hold his breath in a situation like this. Tense the forearm, shake the knife down across his palm. A seven-inch blade, long enough to get through clothing and into a vital organ. Silent weapon. Silent death.

Laughter. The cadence and intonation of Italian. He was listening to the approach of some Baldoni. Soon enough he could recognize the voices. That was Cousin Tonio, who was too good-looking and confident to be quite reliable on a job. Maybe. Or maybe Tonio enjoyed playing the likable rogue. The English branch of the Baldoni’s well-respected and meticulously managed Banca della Toscana had not been placed in the hands of a fool.

The other voices must be Alessandro and the young Giomar.

They strolled past him, not seeing him. They were dressed in cloaks of invisibility themselves, the patched, secondhand garments of the poor. Groom, hod carrier, mason’s apprentice, bootblack, stevedore, butcher’s boy . . . they could have been any of those. They wore poverty and an exuberant vulgarity as if they’d been born to it. Anyone who saw them on Semple Street would know they were up to no good, poking and prying about, hoping for some trifles that weren’t nailed down.

But, if the Merchant saw them or heard them described, he’d never suspect them of scouting out the territory. All the cold intelligence of the Merchant, and he had no sense of humor. He’d never understand the Baldoni appetite for exuberant gestures.

They passed, laughing, talking about music, climbed the front stairs, and pushed into the house.

His opportunity. Any attention would be on them. He went over the high wall to the side of the house and into the garden. Ran to the back garden and entered a slice of shadow he’d picked out the last time he was here.

The Baldoni, enterprising crew that they were, left a lantern burning at the back of the house in the window beside the kitchen door. Somebody might want to get in, quietly, at an odd hour.

One of the household dogs scented a stranger on the wind and whuffed a warning but the boisterous entry to the kitchen and demands for food covered that up. It wasn’t repeated. Perhaps the dog was one of the ones he’d snuck food to earlier.

He breathed quietly and waited. Ten or fifteen minutes passed. Behind the brick and mortar, in the kitchen, voices lowered to sober conversation. A dog whined and Alessandro’s complaint quieted it. A woman’s voice spoke. The windows up and down the house stayed dark. They must be used to feeding their young men at midnight.

He remained undetected, but there was watchfulness in the Baldoni household, a sense of somebody awake besides those men in the kitchen. He’d snuck into army camps that were less alert. Whatever quarrels he might have with the Baldoni in the future, tonight he was glad Cami rested in her bed with a couple dozen dishonest, competent, cynical Tuscans between her and harm.

Upstairs, over the kitchen, one window was lit by more than the red light of a banked fire. Somebody’d left a candle burning in the window in the corner room at the far end.

That would be Cami, waiting for him. He hadn’t asked her to wait. He hadn’t expected to come to her. Yet, here he was.

A wooden shed backed to the house directly below the window. It was no challenge to hook his boot into a rough board and draw himself up to the shed roof, which was embedded with broken glass. Somebody’d spread a wool blanket over some of it. That could be some enterprising young Baldoni sneaking in and out. It could be Cami’s fine hand.

He scrambled across without noise, hands and feet spread to support his weight.

She’d thrown the sash up. A slit in the curtain showed a bedroom of tidy whitewashed walls and a dark, shiny wood floor, with a rag rug in front of the hearth. The dressing table would belong to a woman. The framed paintings on the wall, to a young girl.

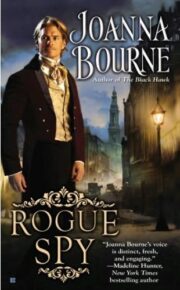

"Rogue Spy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Rogue Spy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Rogue Spy" друзьям в соцсетях.