‘Come and feed the fish,’ said Rupert, taking Sarah’s hand.

He led her down a grassy ride, flanked on either side by yew hedges, to the fish pond. Stuffed to bursting by Simon Harris’s monsters, the carp didn’t even bother to ruffle the surface of the water lilies.

‘Any repercussions?’ asked Rupert.

Sarah shook her head. ‘It seems funny, belting away from your tennis court with a pink dress over my head. The entire Gloucestershire fire brigade will recognize my bush, but not my face.’

Rupert grinned, and pulled her inside the thick curtain of a weeping ash. After he’d kissed her, he said: ‘When are we going to finish the set?’

‘Very soon, please.’

Her smooth golden face was green in the gloom; she looked like a water nymph.

‘How was Maud O’Hara?’ she asked.

‘Seemed pretty unmoored to me,’ said Rupert.

‘Looks as though she’d like to tie herself to you.’

‘Were you jealous?’

Sarah nodded.

‘Pity your husband’s summer recess coincides with mine.’

‘He’s never away,’ moaned Sarah, as Rupert’s fingers moved between her legs. ‘Why don’t we nip into the gazebo?’

‘Got to pick up the children. I’m late already.’

‘When am I going to see you?’ gasped Sarah, as Rupert’s other hand slid down underneath her pants at the back.

‘Come to Ireland with me. I’m leaving on Wednesday afternoon.’

‘I can’t. My ghastly step-children are coming for a couple of weeks on a trial visit. I know who it’s going to be a trial to as well. Paul’s going to Gatwick on Tuesday to meet them.’

‘That’ll give us at least five hours. Ring me at home the minute he leaves.’

‘Hulloo,’ called a male voice.

Frantically straightening her dress, Sarah shot out through the ash tree curtain and bent once more over the fish pond to hide her flaming face.

Wiping off her pale-pink lipstick, Rupert followed in a more leisurely fashion.

‘Sarah and I were talking about horses,’ he told an apoplectic Paul. ‘If you’re going to fork out for a groom, feed and grazing for two hunters, you’re talking about at least fifteen thousand a year. Better if Sarah kept something at my yard.’

‘We’ll discuss it in our own time, thank you,’ spluttered Paul. ‘We must go, Sarah.’

Back in the conservatory, Maud was being heavily chatted up by Bas.

‘Shove off, Bas,’ Monica told him. ‘Declan wants to go and I want two minutes with Maud.’

‘I’ll come and see you,’ said Bas, blowing Maud a kiss.

He’s very attractive, thought Maud dreamily, but not in Rupert’s class.

‘I’m sure you’re a joiner,’ said Monica, who was now busily dead-heading a pale-blue plumbago growing up a whitewashed trellis.

‘No,’ said Maud, ‘I’m an actress.’

Very firmly, but charmingly, she managed to resist all Monica’s urging that she should get herself involved in any kind of charity work.

‘The children come first,’ said Maud simply.

‘But two of them are away,’ protested Monica, ‘and Taggie’s eighteen.’

‘But still dyslexic,’ sighed Maud. ‘She needs her mother, and of course Declan needs his wife.’

‘But you must do something for charity,’ persisted Monica. ‘It’s such a good way of meeting new people, and it’s awfully easy to get bored in the country.’

‘I never get bored,’ lied Maud. ‘There’s so much to do to the house. I can’t pass a traffic light at the moment without wondering whether yellow would go with red in one of the children’s bedrooms.’

Driving home, Maud put a hand on Declan’s thigh, edging it upwards. Pixillated by Rupert’s interest, and Bas’s extravagant compliments, hazy with drink, she felt wildly desirable and alive again.

‘Let’s go straight to bed.’

‘What about Taggie?’ said Declan.

‘Say we’re both tired.’

Declan curled a hand into the front of her black dress.

‘They all wanted you.’

‘Did you like that?’ whispered Maud.

‘I know how hard I’ve got to fight to keep you,’ he said harshly and felt her nipples hardening.

Back in their bedroom at The Priory, he undressed her slowly down to her suspender belt and stockings, so black against the soft white skin.

‘When did you get those bruises?’ she said sharply, as he took off his shirt.

‘This morning. The focking mowing machine kept stopping and I didn’t.’

12

Gertrude, the mongrel, was walked off her feet in the next three days. When Maud wasn’t drifting up and down the valley in a new lilac T-shirt and matching flowing skirt, hoping to bump into Rupert, Declan was striding through the woods, trying to work out what questions he would ask Johnny Friedlander and driving Cameron Cook crackers because he was never in when she wanted to talk to him.

Cameron’s patience was further taxed by her PA getting chicken-pox, and having to be replaced by Daysee Butler, easily the prettiest girl working at Corinium but also the stupidest.

‘Why d’you spell Daisy that ludicrous way?’ snarled Cameron.

‘Because it shows up more on credits,’ said Daysee simply.

Like all PAs that autumn, Daysee wandered round clutching a clipboard and a stopwatch, wearing loose trousers tucked into sawn-off suede boots, and jerseys with pictures knitted on the front.

‘It’s just like the Tit Gallery with all these pictures floating past,’ grumbled Charles Fairburn.

Programme day dawned at The Priory with Declan roaring round the house.

‘Whatever’s the matter?’ asked Taggie in alarm.

‘I have absolutely no socks. No, don’t tell me. I’ve looked behind the tank in the hot cupboard, and in all my drawers, and in the dirty clothes basket. Utterly bloody Patrick and utterly bloody Caitlin swiped all my socks when they went back, so I have none to wear.’

‘I’ll drive into Cotchester and get you some,’ said Taggie soothingly.

‘Indeed you will not,’ said Declan. ‘I’m driving into Cotchester, and I’m buying thirty pairs of socks in such a disgossting colour that none of you will ever wish to pinch them again.’

He was very tired. He hadn’t slept, panicking Johnny might roll up stoned or not at all. And yesterday he and Cameron had been closeted together for twelve hours in the edit suite, putting together the introductory package, rowing constantly over what clips and stills they should use. Daysee Butler’s inanities hadn’t helped either. Nor had Declan’s dismissing as pretentious crap an alternative script Cameron pretended one of the researchers had written, but which she in fact had toiled over all weekend. She couldn’t run to Tony, who was in an all-day meeting in London, but got her revenge while Declan was recording his own beautifully lyrical script, by making him do bits over and over again because of imagined mispronunciations or technical faults or hangings outside. They parted at the end of the day not friends.

Having bought his socks, Declan arrived at the studios around five. A game show was underway in Studio 2; the Floor Manager was flapping his hands above his head like a demented seal as a sign to the audience to applaud. Midsummer Night’s Dream had ground to a halt in Studio 1, because Cameron, dissatisfied with the rushes, had tried to impose an ‘out-of-house lighting cameraperson’ on the crew, who had promptly downed tools. The Rude Mechanicals, with no prospect of a line all day, were getting pissed in the bar.

Deferential, glad-to-be-of-use, Deirdre Kilpatrick, the researcher on ‘Cotswold Round-Up’, as dingy as Daysee Butler was radiant, was taking a famous romantic novelist to tea before being interviewed by James Vereker.

‘James will ask you your idea of the perfect romantic hero, Ashley,’ Deirdre was saying earnestly. ‘And it’d be very nice if you could say: “You are, James”, which would bring James in.’

‘I only go on TV because my agent says it sells books,’ said the romantic novelist. ‘Oooh, isn’t that Declan O’Hara? Now, he is the perfect romantic hero.’

Declan slid into his dressing-room and locked the door. A pile of good luck cards and telexes awaited him. He was particularly touched by one from his old department at the BBC saying, ‘Sock it to them.’

‘Da-glo yellow sock it to them,’ said Declan, chucking thirty pairs of socks in luminous cat-sick yellow on the bed.

There was a knock on the door. It was Wardrobe.

‘D’you want anything ironed?’

Declan peered gloomily in the mirror: ‘Only my face.’

He gave her his suit, light grey and very lightweight, as he was going to be under the hot lights for an hour. She hung up his shirt and tie, then squealed with horror at the yellow socks.

‘You can’t wear those.’

‘They won’t show,’ said Declan.

In Studio 3 two technicians were sitting in Declan’s and Johnny’s chairs, while the crew sorted out lighting and camera angles. Crispin, the set designer, whisked about in a lavender flying-suit. The set was exactly as Declan had wanted, except the Charles Rennie Mackintosh chairs had been replaced by wooden Celtic ones, with the conic back of Declan’s rising a foot above his head like a wizard’s chair: a symbol of authority and magic.

As a gesture of defiance, on the steel-blue tables which rose like mushrooms at the side of each rostrum, Crispin, the designer, had placed blue-and-red-striped glasses and carafes.

‘I want plain glasses,’ snapped Declan.

‘Oh, they’re so dreary.’ Crispin pouted.

‘I want them — and get rid of those focking flowers.’

‘Cameron ordered them specially.’

Declan picked up the bouquet threateningly.

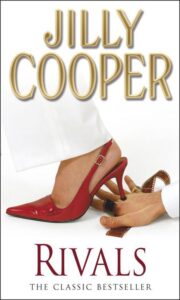

"Rivals" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Rivals". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Rivals" друзьям в соцсетях.