“It doesn’t give the German for ‘whoa.’ You’ll have to fall back on dummkopf, lieberlein, and achtung.”

“Or auf wiedersehen,” said Jake, “as Clara bucks me off and gallops off into the sunset.”

“The American for whoa, must be starp, starp,’ she went on.

“You remember that red T-shirt you wore when Revenge won at Olympia?” said Jake.

“I’ve got it here,’ said Fen.

“D’you mind wearing it this afternoon?”

Fen did mind very much. It was impossibly hot and she’d got very burnt yesterday, and the red T-shirt would clash with her face. But it was Jake’s day; she mustn’t be selfish.

“Of course not,’ she said.

Jake was encouraged by the number of telegrams. British hopes rested with Rupert, but Jake had generated an enormous amount of goodwill. People were obviously delighted to see him back at the top again. There were telegrams from the Princess and one from the colonel of the regiment at Knightsbridge Barracks, who’d somehow discovered that their old horse Macaulay had ended up with Jake. The one that pleased him most was from Miss Blenkinsop in the Middle East. He knew that she, as much as he, enjoyed the sheer pleasure of showing the world that he could succeed with a horse Rupert had thrown out. Every time Macaulay won anything, he’d religiously taken 10 percent of the winnings and posted them to Miss Blenkinsop for her Horse Rescue hospital. If he won today, she would get £1,000.

If he won, “Oh my God,” he said, and bolted out of the caravan, through a crowd of reporters, and into the lavatory, where he brought up his breakfast.

“Why don’t you bloody well go away?” shouted Fen to the reporters. “You know you won’t get any sense out of him before a big class.”

In the end they had to be content with interviewing Darklis, who sat on a hay bale, smiling up at them with huge black eyes.

“My daddy’s been thick four times this morning. He doesn’t theem to like French food. I love it. We’ve had steak and chips every single night.”

At last there was the course to walk, which made Jake feel even worse. It was far bigger than he’d imagined. The water jump seemed wider than the Channel. The heavy, thundery, blue sky seemed to rest on the huge soaring oxblood red wall, and Jake could actually stand underneath the poles of the parallel.

Malise, walking beside him, winced at the French marigolds, clashing with purple petunias and scarlet geraniums in the pots on either side of each jump. How could the French have such exquisite color sense in their clothes and not in their gardening?

A couple of English reporters sidled up to them. “Did you really pull a knife on Rupert, Gyppo.”

“Bugger off,” said Malise. “He’s got to memorize the course. Do you want a British victory or not? That’s tricky,” he added to Jake, looking at the distance between the parallels and the combination. “It’s on a half-stride. The water’s a brute. You’ll get hardly any run in there. You’ll need the stick.”

“Macaulay never needs a stick,” said Jake through frantically chattering teeth. The sheer impossibility of getting Snakepit, let alone President’s Man, over any of the fences paralyzed him with terror.

Rupert walked with Colonel Roxborough, wearing dark glasses, but no hat against the punishing Brittany sun. He seemed totally oblivious of the effect he was having on the French girls in the crowd. The German team walked together, so did the Americans. Count Guy, in a white suit made by Yves St. Laurent, was the object of commiseration. Over his great disappointment now, he shrugged his shoulders philosophically. At least he didn’t have to jump five rounds in this heat and his horses would be fresh for Crittleden the following week.

In the collecting ring, Ivor Braine had been cornered by the press and was telling them, in his broad Yorkshire accent, that he was convinced Jake had been brandishing a knife because the steaks were so tough.

“I wish Saddleback Sam had made it,” said Humpty for the thousandth time.

Driffield was busy selling a horse at a vastly inflated price to one of the Mexican riders.

“Wish it was a wife-riding contest,” said Rupert. “I wouldn’t mind having a crack at Mrs. Ludwig, although I would draw the line at Mrs. Lovell.”

Once again he wished Billy were there. He’d never needed his advice more, or his silly jokes, to lower the tension. Obviously drunk at ten o’clock in the morning, Billy had already rung him to wish him luck.

Rupert had asked after Janey. Billy had laughed bitterly. “She’s like a wet log fire. If you don’t watch her all the time, she goes out.”

Next week, reflected Rupert grimly, he was going to have to take Janey out to lunch and tell her to get her act together.

Despite the lack of a French rider in the final, all the publicity had attracted a huge crowd. There wasn’t an empty seat or an inch of rope unleaned over anywhere. Malise sighed. If there was a British victory, all the glare of bad publicity of the feuds between riders might be forgotten. He watched Rupert, cool as an icicle, putting Snakepit over huge jumps in the collecting ring. Jake was nowhere to be seen. He was probably being sick again.

At two o’clock, each of the four finalists came on, led by their own band. Ludwig came first, to defend his title on the mighty Clara, yellow browband matching the yellow knots in her plaits. Her coat was the color of oak leaves in autumn, her huge chest like a steamer funnel. Unruffled by the crowd, her eyes shone with wisdom and kindness.

Then came Dino on the slender President’s Man, who looked almost foal-like in his legginess. The same liver chestnut as Clara, he seemed half her size. Dino lounged, totally relaxed in the saddle, like a young princeling, his olive skin only slightly paler than usual, hat tipped over his nose, as though he was taking the piss out of the whole proceedings.

Then Rupert, eyes narrowed against the sun, the object of whirring cameras and cheers from the huge British contingent, motionless in the saddle as the plunging, eyerolling Snakepit shied at everything and fought for his head.

And, finally, Jake, his set face as white as Macaulay’s, who strutted along, pointing his big feet, enjoying the cheers.

Like a council of war, the four riders lined up in front of the president’s box, the bands forming a brilliant scarlet and gold square behind them. Les Rivaux can seldom have produced a more breathtaking spectacle, with the flags, limp in the heat, the scarlet coats, the plumes of the soldiers, the gleaming brass instruments, the grass emerald green from incessant sprinkling, the forest, which seemed to smoulder in its dark green midgy stillness, and in the distance the speedwell blue gleam of the sea. The bands launched into the National Anthem, each crash of cymbal and drum sending Snakepit and President’s Man cavorting around in terror. Macaulay and Clara stood like statues at either end of the row.

Fen, body aching from grooming, fingers sore from plaiting, her red T-shirt drenched with sweat, waited for Macaulay to return to the collecting ring. She was far more nervous than usual. She had a far bigger part to play. With the three other grooms she would spend the competition in the cordoned-off part of the arena and change Jake’s saddle onto each new horse. Nearby was Dizzy, braless and ravishing in a pink T-shirt, her newly washed blond hair trailing pink ribbons. One day I’m going to look as good as her, vowed Fen. Then she squashed the thought of her own presumption and had another look at the vast fences. How absolutely terrifying for Jake. The field emptied, large ladies bustled round with tape measures, checking poles for the last time.

“I’ve bet a hundred on Campbell-Black,” said the colonel in an undertone to Malise. “I reckon it’ll be a jump-off between him and Ludwig, with the American third and Lovell nowhere. He simply hasn’t got the nerve.”

Helen, seeing the riders in their red coats, was reminded of the first day she’d met Rupert out hunting.

“Dear God,” she prayed, “please restore my marriage and make him win, but only if you think that’s right, God.”

Tory, in the riders’ stand, with Darklis and Isa, prayed the same for Jake, but without any qualification.

“I wonder when Daddy’s going to be thick again,” said Darklis.

Then a hush fell as in came Ludwig. As he rode past the president’s box and took off his hat, the rest of the German team, who’d all been at the champagne, rose to their feet, shooting up their hands in a Heil Hitler salute, to the apoplexy of Colonel Roxborough, who went as scarlet as his carnation.

The only sound was the snort of the horse, the thunder of hoofs, and the relentless ticking of the clock. Girding her great chestnut loins, a symbol of reliability, Clara jumped clear.

Malise lit a cigar. “At least we know it’s jumpable,” he said.

Dino came in, talking quietly to the young horse.

“That’s a pretty horse,” said Malise.

And a pretty rider, thought Helen, who was sitting near him.

Being so much slighter, President’s Man seemed to go twice as fast. Dino’s thrusting acrobatic style and almost French elegance and good looks soon had the crowd cheering. He also went clear.

Then came Rupert, hauling on the plunging Snakepit’s mouth, hotting him up so he fought for his head all the way around. By some miracle of timing and balance, he too went clear, and Snakepit galloped out of the ring, giving two colossal bucks and nearly trampling a crowd of photographers under foot.

“God help those who come after,” sighed Malise.

“I’m not taking a penny less than £30,000,” said Driffield.

Fen gave Macaulay a last-minute pat and a kiss.

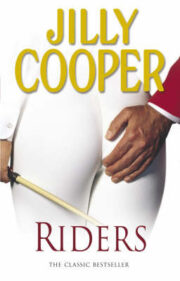

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.