After fourteen hours’ sleep, Jake woke feeling much better. He didn’t know whether Malise had had a word with them, but all the team were particularly nice to him as they set off out of Madrid in an old bus, across dusty plains, like the hide of a great slaughtered bull, then through rolling hills dotted with olive trees and orange groves. The road was full of potholes, sending sledgehammer blows up Jake’s spine as the back wheels went over them. Rupert sat next to Helen with his arm along the back of the seat, but not touching her because it was too hot. Billy sat in front, talking constantly to them, refereeing any squabbles, sticking up for Helen. Lavinia Greenslade sat with her father. Humpty sat with Jake and talked nonstop about Porky Boy.

Only Rupert didn’t let up in his needling. Every donkey or mule or depressed-looking horse they passed reminded him of Sailor or “Jake’s Joke,” as he now called him.

They lunched at a very good restaurant, sitting outside under the plane trees, eating cochinella or roast suckling pig. It was the first square meal Jake had been able to keep down since he arrived. While they were having coffee, a particularly revolting old gypsy woman came up and tried to read their fortunes.

“Do tell your ghastly relation to go away, Jake,” said Rupert.

Helen, beautiful, radiant, and clinging, was surprised Rupert was being so poisonous to this taciturn newcomer. She tried to talk to Jake and ask him about his horses, but, aware that he was being patronized, he answered abruptly and left her in midsentence.

Afterwards they went to a bull farm and tried playing with the young bulls and heifers with padded horns and a cape. Rupert and Billy, who’d both had a fair amount to drink at lunchtime, were only too anxious to have a go. Humpty, who’d eaten too much suckling pig (“You might pop if a horn grazed you,” said Rupert), refused to try, and so did Jake.

Side by side, but both feeling very different emotions, Jake and Helen watched Rupert, tall and lean, a natural at any sport, swinging away as the little bull hurtled towards him. Determined to excel, he was already getting competitive. Billy, fooling around, couldn’t stop laughing, and was finally sent flying and only pulled out of danger just in time by Rupert. In the end Rupert only allowed himself to be dragged away because they had to be in Madrid to watch a bullfight at six. Before the fight, they were shown the chapel where the matadors pray before the fight.

“Do with a session in there before tomorrow afternoon,” said Billy. “Dear God, make us beat the Germans.”

The bullfight nauseated Jake, particularly when the picadors came on, riding their pathetic, broken-down, insufficiently padded horses. If they were gored, according to Humpty, they were patched up and sent down into the ring to face the ordeal again. They were so thin they were in no condition to run away. The way, too, that the picadors were tossing their goads into the bull’s neck to break his muscles reminded Jake of Rupert’s method of bullying.

The cochinella was already churning inside him.

“I say, Jake,” Rupert’s voice carried down the row, “doesn’t that picador’s horse remind you of Sailor. If you popped down to the Plaza de Toros later this evening, I’m sure they’d give you a few pesetas for him.”

Jake gritted his teeth and said nothing.

“That’s wight,” whispered Lavinia, who was sitting next to him. “Don’t wise. It’s the only way to tweat Wupert.”

Jake felt more cheerful, particularly when, the next moment, Lavinia plucked at his sleeve, saying, “Can I wush past you quickly? I’m going to be sick.”

“I’ll come with you,” said Jake.

Neither of them was sick but on the way home enjoyed a good bitch about Rupert. The rest of the team went out to a party at the Embassy. Jake followed Malise’s advice and went to bed early again.

On the morning of the Nations’ Cup, Jake woke feeling better in body but not in mind. The sight of fan mail and invitations so overcrowding Rupert’s pigeonhole that they spilled over into Humpty’s and Lavinia’s on either side gave him a frightful stab of jealousy.

Then in his own pigeonhole he found a letter from Tory, which filled him equally with remorse and homesickness. “Darling Jake,” she wrote in her round, childish hand, “Isa and Wolf and all the horses and Tanya and most of all me (or should it be I) are missing you dreadfully. But I keep telling myself that it’s all in a good cause, and that by the time you get this letter, you’ll have really made all the other riders sit up, particularly Rupert. Is he still as horrible or has marriage mellowed him? I know you’re going to do really well.”

Jake couldn’t bear to read any more. He scrumpled up the letter and put it in his hip pocket. Skipping breakfast, he went straight down to the stables. He wanted to work the horses before it got too punishingly hot.

Walking into the British tackroom, he steeled himself for whatever grisly practical joke was on the menu today, but he found everything in place. Because it was Nations’ Cup Day, everyone was far too preoccupied. The grooms were tense and distracted, the horses edgy. They knew something was up. Jake worked both the horses and was pleased to find Sailor had recovered from the bout of colic he’d had earlier in the week, and Africa’s leg was better.

Back in the yard he cooled down Sailor’s legs with a hose, amused by the besotted expression on the horse’s long speckled face. Nearby, Tracey was washing The Bull’s tail. Beyond her, Rupert’s groom, Marion, was standing on a hay bale to plait the mighty Macaulay’s mane, showing off her long brown legs in the shortest pale blue hot pants and grumbling about the amount of work she had to get through. Macaulay was so over the top that, rather than risk hotting him up, Rupert had decided to ride Belgravia in the parade beforehand and bring out Macaulay only for the actual class. This meant Marion had two horses to get ready.

Jake, who’d been carefully studying Rupert’s horses, thought they were getting too many oats. No one could deny Rupert’s genius as a rider, but his horses were not happy. He had surreptitiously watched Rupert take Mayfair, Belgravia, and Macaulay off to a secluded corner of the huge practice ring and seen how he made Tracey and Marion each hold the end of the top pole of a fence, lifting it as the horses went over to give them a sharp rap on the shins, however high they jumped. This was meant to make them pick up their feet even higher the next time. The practice, known as rapping, was strictly illegal in England.

Jake, however, was most interested in Macaulay. He was a brilliant horse, but still young and inexperienced. Jake felt he was being brought on too fast.

In the yard the wireless was belching out Spanish pop music.

“I do miss Radio One,” said Tracey.

The Italian team came past, their beautifully streaked hair as well cut as their jeans, and stopped to exchange backchat with Marion and Tracey.

As Jake started to dry Sailor’s legs, the horse nudged at his pocket for Polos.

“How long have we got?” Tracey asked Marion.

“About an hour and a half before the parade.”

“Christ,” said Tracey, plaiting faster. “I’m never going to be ready in time. Give over Bull, keep still.” The Bull looked up with kind, shining eyes.

“You want a hand?” asked Jake. “I’ve nearly finished Sailor.”

“You haven’t,” said a voice behind him.

It was Malise Gordon, looking elegant, even in this heat, in a pale gray suit, but extremely grim.

“You’re going to have to jump after all,” he said. “That stupid idiot, Billy, sloped off this morning with Rupert to have another crack at bullfighting and got himself knocked out cold.”

Tracey gave a wail and dropped her comb. The Bull jerked up his head.

“It’s all right. He’ll live,” said Malise irritably. “The doctor doesn’t think it’s serious, but Billy certainly doesn’t know what day of the week it is and there’s no chance of him riding.”

Tracey burst into tears. Marion stopped plaiting and put her arms round Tracey, glaring at Jake as though it was his fault.

“He’s got a head like a bullet; don’t worry,” Marion said soothingly.

“Come on,” said Malise, not unkindly. “Pull yourself together; put The Bull back in his box and get moving on whoever Jake’s going to ride. Africa, I presume.”

Jake shook his head. “Her leg’s not right. I’m not risking it. I’ll ride Sailor.”

For a second Malise hesitated. “You don’t want to jump The Bull?”

Catching Tracey’s and Marion’s looks of horror, Jake shook his head. If by the remotest chance he didn’t let the side down, he was bloody well not having it attributed to the fact that he wasn’t riding his own horse.

“All right, you’d better get changed. You’re meant to be walking the course in an hour, but with the general coming and Spanish dilatoriness it’s impossible to be sure.”

Luckily Jake didn’t have time to panic. Tracey sewed the Union Jack onto his red coat. Normally he would have been fretting around, trying to find the socks, the breeches, the shirt and the white tie which he wore when he last won a class. But as it was so long since he had won anything, he’d forgotten which was the last set of clothes that worked. His face looked gray and contrasted with the whiteness of his shirt like a before-and-after laundry detergent ad. His hands were trembling so much he could hardly tie his tie, and his red coat, which fitted him before he left England, was now too loose. Then suddenly, when he dropped a peseta and was searching for it under the forage bin, he found his tansy flower, slightly battered but intact. Overjoyed, he slipped it into his left boot. Aware of it, a tiny bump under his heel, he felt perhaps his luck might be turning at last.

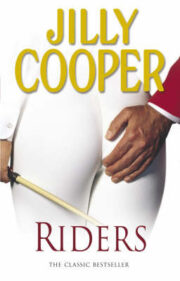

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.