“He drove into a booby trap, killed outright, which I suppose was a mercy.”

“But not for you,” said Helen. “You weren’t able to say good-bye.”

Oh hell, she said to herself, that’s why he was reading that Rupert Brooke poem. And I came barging in with all my problems.

“Were you very close?” she asked.

“Yes, I think so. The awful thing was that I’m not sure he really wanted to go into the Army at all. Just felt he ought to because my father had a dazzling war and…”

“And you got an MC, Billy told me.”

“But Timmy was really rather a rebel. We had an awful row. He’d got some waitress pregnant, felt he ought to marry her. He didn’t love her, he just had principles. We tried to dissuade him. His last leave was all rows, my wife in hysterics.”

“What happened to the baby?”

“It was a false alarm, which made the whole thing more ironic. Now I wish it hadn’t been. At least we’d have something of him left.”

They had reached London now. When they got to Regina House he got out as well. A few stars had managed to pierce the russet haze hanging over London. Lit from behind by the street-light, there were no lines on his face.

Helen swallowed, took a deep breath to conquer her shyness, and stammered, “I always dreamed English men would be just like you, and it’s taken me six months in this country to find one,” and, putting her hand on his shoulder, she kissed him quickly on the cheek. “Thank you so much for my lift. I do hope we meet again.”

“Absolutely no doubt about that,” said Malise. “Young Rupert’ll be on the warpath in no time. But listen to an old campaigner: play it cool, don’t let him have it all his own way.”

Malise let himself into his Lowndes Street flat and switched off the burglar alarm. It was a cheerless place. His wife had conventional tastes, tending to eau de nil wallpaper, overhead lights, and Sloane Square chintz. She was away in the country, eventing with their daughter. The marriage had not been a success. They had stayed together because of the children, but now there was only Henrietta left. In the drawing room, on an easel standing on a dust sheet, was an oil painting of a hunting scene Malise was restoring. He could finish it in two hours. He didn’t feel tired. Instead, he poured himself a glass of brandy and set to work, thinking about that exquisite redhead. She was wasted on Rupert. He was not entirely sure of his motives in whisking her back to London. Was it a desire to put Rupert down, or because he couldn’t bear the thought of Rupert sleeping with her tonight, forcing his drunken hamfisted attentions on her? For a minute he imagined painting her in his studio, not bothering to turn on the lights as dusk fell, then taking her across to the narrow bed in the corner and making love to her so slowly and gently she wouldn’t realize it had been miraculous until it was all over.

He cursed himself for being a fool. He was fifty-two, thirty years her senior, probably a disgusting old man in her eyes. Yet she had stirred him more than any woman he had met for years.

She’d have done for Timmy. He picked up the photograph on the piano. The features that smiled back at him were very like his own, but less grim and austere, more clear-eyed and trusting.

Were Rupert and Billy and Humpty merely Timmy substitutes? Was that why he’d taken the job of chef d’equipe? After six months he was surprised, almost indignant, at the pain. Putting the photograph down, he slumped on the sofa, his face in his hands.

As Helen let herself into Regina House the telephone was ringing. “Shush, shush,” she pleaded, and, rushing forward, reached the receiver just before the principal of the hostel, furious and bristling in her hairnet.

“It’s one o’clock in the morning,” she hissed, “I won’t have people ringing so late.”

But Helen ignored her, hunching herself over the telephone to ward off the outside world. Praying as she’d never prayed before, she put it to her ear.

“Hello,” said a slightly slurred voice, “can I speak to Helen Macaulay?”

“Oh yes, you can, this is she.”

“Bloody bitch,” said Rupert, “waltzing off with the one man in the room I can’t afford to punch on the nose.”

Helen leant joyously against the wall, oblivious of the gesticulating crone in the hairnet.

“Are you okay?” Rupert went on.

“Fine. Where are you?”

“Back in my horrible little caravan — alone. I’ve got your dress here, like a shed snakeskin. It reeks of your scent. I wish you were here to fill it.”

“Oh, so do I,” said Helen. Again at a distance, she felt free to come on more strongly.

“Look, I’m on the road this week and most of next. I haven’t really got myself together, but I’ll ring you towards the end of the week, and I’ll try and get up to London on Monday or Tuesday.”

“Rupert,” she pleaded, “I didn’t want to go off with Malise. It was just that you seemed so otherwise engaged all evening.”

“Trying to make you jealous didn’t work, did it? Won’t try that again in a hurry.”

13

For the next few weeks Rupert laid siege to Helen, throwing her into total confusion. On the one hand he epitomized everything she disapproved of. He was flip — except about winning — spoilt, philistine, hedonistic, immoral, and very right-wing — eating South African oranges just to irritate her, and in the street, which her mother had drummed into her one must never do. The few dates they were able to snatch in between Rupert’s punishing show-jumping schedule and Helen’s job always ended in rows because she wouldn’t sleep with him.

On the other hand she had very much taken to heart Malise’s remarks about Rupert’s disturbed childhood and the possibility that he might be redeemed by a good marriage. Could she be the one to transform this wild boy into the greatest show jumper of his age? There was a strong element of reforming zeal in Helen’s character; she had a great urge to do good.

Princess Anne had also just announced her engagement to Mark Phillips and every girl in England was in love with the handsome captain, who looked so macho in his uniform and who, despite being pretty unforthcoming when interviewed on television, was obviously a genius with horses. Princess Anne looked blissfully happy. And when one considered Rupert was just as beautiful as Captain Phillips, and extremely articulate when interviewed about anything, did it matter, pondered Helen as she tossed and turned in her narrow bed in Regina House, reading A. E. Housman and Matthew Arnold, that she and Rupert couldn’t talk about Sartre and Henry James? He was young. He could learn. Malise said he was bright.

Anyway, all this fretting was academic because Rupert hadn’t mentioned marriage or said that he loved her. But he rang her from all over Europe and managed to snatch an evening, however embattled, with her about once a fortnight, and he had invited her to fly out to Lucerne for a big show at the beginning of June, so she had plenty of hope to sustain her.

Meanwhile the IRA were very active in London, exploding bombs; everyone was very jumpy, and her mother wrote her endless letters, saying that she need no longer stay in England a year, that things sounded very hazardous, and why didn’t she come home. Helen, who would have leapt at the chance all through the winter, wrote back saying she was fine and that she had a new beau.

Rupert sat with his feet up on the balcony of his hotel bedroom overlooking the Bois de Boulogne. After a class at the Paris show that ended at midnight the previous night, he was eating a late breakfast. Wearing nothing but a bath towel, his bare shoulders already turning dark brown, he was eating a croissant with apricot jam and trying to read War and Peace.

“I can’t understand this bloody book,” he yelled back into the room. “All the characters have three names.”

“So do you,” said Billy, coming out onto the balcony, dripping from the bath and also wrapped in a towel. He looked at the spine of the book. “It might help if you started with Volume One, not Volume Two.”

“Fucking hell,” said Rupert, throwing the book into the bosky depths of the Bois and endangering the lives of two squirrels, “that’s what comes of asking Marion to get out books from the library.”

“Why are you reading that junk anyway?”

Rupert poured himself another cup of coffee. “Helen says I’m a philistine.”

“She thinks you’re Jewish?” said Billy. “You don’t look it.”

“I thought it meant something to do with Sodom and Gomorrah until I looked it up,” said Rupert, “but it just means you’re pig ignorant, deficient in culture, and don’t read enough.”

“You read Horse and Hound,” said Billy indignantly, “and your horoscope and the racing results, and Dick Francis.”

“Or go to the the-ater, as she calls it.”

“I should think not after that rubbish she dragged us to the other night. Anyway, you went to a strip club in Hamburg last week. I’ve heard people call you a lot of things, but not stupid.”

He bent down to pick up his hairbrush which had dropped on the floor, and winced. “I don’t know what they put in those drinks last night but I feel like hell.”

“I feel like Helen,” said Rupert. “I spent all last night trying to ring her up. I got hold of the London directory, but I couldn’t find Vagina House anywhere.”

“Probably looked it up under ‘cunt,’ ” said Billy.

Rupert laughed. Then a look of determination came over his face. “I’ll show her. I’ll write her a really intellectual letter.” He got Helen’s last letter, all ten pages of it, out of his wallet. “I can hardly understand hers — it’s so full of long words.” He smoothed out the first page. “She hopes we take in the Comédie Française and the Louvre, and then says that just looking at me elevates her temperature. Christ, what have I landed myself with?”

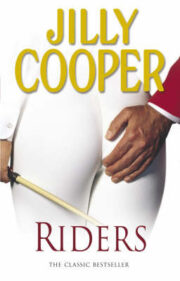

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.