“Shut up,” hissed Jake. “Now shove off.”

“Please let me stay. There’s nothing to do at home. I couldn’t sleep. I will help. Oh, doesn’t Smokey look sweet curled up in the rug? Are you really taking Africa?”

“Mind your own business,” said Jake.

Fen took the boiled sweet out of her mouth and gave it to Dandelion, who was slavering over the next half-door, then kissed him on the nose. Her shirt was already escaping from the jeans which she wore over her jodhpurs to keep them clean.

“Does Mrs. Wilton know?” she asked.

“No,” said Jake.

“I won’t tell her,” said Fen, swinging on Africa’s door. “Patty Beasley might, though, or Sally Ann; she’s always sneaking about something.”

Jake had already sweated uncomfortably over this possibility.

“They’re probably too thick to notice,” she went on. “Shall I make you a cup of tea? Four spoonfuls of sugar, isn’t it?”

Jake relented. She was a good kid, cheerful and full of guts, with an instinct for horses and a knowledge way beyond her nine years.

“You can stay if you keep your trap shut,” he said. “I don’t want Mrs. Wilton waking up yet.”

After she had spilt most of the tea in the saucer, Fen tied Dandelion up outside Africa’s box and settled down to washing his white patches, managing to get more water over herself than the pony.

Jake half-listened as she chattered on incessantly about her sister Tory, who was doing the season but not enjoying the parties at all, and who often had red eyes from crying in the morning.

“She’s coming to the show later.”

“Does your mother know you’re here?” asked Jake.

“She wouldn’t notice if I wasn’t. She’s got a new boyfriend named Colonel Carter. Colonel Cart-ah, he calls himself. He laughs all the time when he’s talking to Mummy and he’s got big yellow teeth like Dandelion, but somehow they look better on a horse.

“They’re coming to the show, too. Colonel Carter is bringing a lot of soldiers and guns to do a display after the open jumping. He and Mummy and Tory are going to lunch up at the Hall. Mummy bought a new blue dress specially; it’s lovely, but Tory said it was jolly expensive, so I don’t expect she’ll be able to afford to buy me a pony yet; anyway she says Tory being a deb is costing a fortune.”

“Shampoo and set, darling,” she said to Dandelion twenty minutes later as she stuck the pony’s tail in a bucket of hot, soapy water. “Oh, look, Africa’s making faces; isn’t she sweet?” The next moment Dandelion had whisked his tail at a fly, sending soapy water all over Fen, Africa’s rug, and the stable cat, who retreated in high dudgeon.

“For God’s sake, concentrate,” snapped Jake.

“Mummy’s picture’s in The Tatler again this week,” said Fen. “She gets in much more often than poor Tory. She says Tory’s got to go on a diet next week, so she’ll be thin for her drinks’ party next month. Oh cave, Mrs. Wilton’s drawing back the kitchen curtains.”

Hastily Jake replaced Africa’s rug and came out of her box.

Inside the kitchen, beneath the ramparts of honeysuckle, he could see Mrs. Wilton, her brick red face flushed from the previous night’s drinking, dropping Alka-Seltzer into a glass of water. Christ, he hoped she’d get a move on to Brighton and wouldn’t hang around. Picking up the brush and the curry comb he started on one of the ponies.

Mrs. Wilton came out of the house, followed by her arthritic yellow labrador, who lifted his leg stiffly on the mounting block, then as a formality bounded after the stable cat.

Mrs. Wilton was never known to have been on a horse in her life. Stocky, with a face squashed in like a bulldog, she had short pepper and salt hair, a blotchy complexion like salami, and a deep bass voice. All the same, she had had more success with the opposite sex than her masculine appearance would suggest.

“Jake!” she bellowed.

He came out, curry comb in one hand, brush in the other.

“Yes, Mrs. Wilton,” though she’d repeatedly asked him to call her Joyce.

They gazed at each other with the dislike of the unwillingly but mutually dependent. Mrs. Wilton knew that having lost both his parents and spent much of his life in a children’s home, Jake clung on to the security of a living-in job. As her husband was away so much on business, Mrs. Wilton had often suggested Jake might be more comfortable living in the house with her. But, aware that he would have to share a bathroom and, if Mrs. W. had her way, a bedroom, Jake had repeatedly refused. Mrs. Wilton was old enough to be his mother.

But, despite finding him sullen and withdrawn to the point of insolence, she had to admit that the horses had never been better looked after. As a result of his encyclopedic knowledge of plants and wildflowers, and his incredible gypsy remedies, she hadn’t had a vet’s bill since he’d arrived, and because he was frightened of losing this substitute home, she could get away with paying him a pittance. She found herself doing less and less. She didn’t want to revert to getting up at six and mucking out a dozen horses, and it was good to be able to go away, like today, and not worry.

On the other hand, if he was a miracle with animals, he was hell with parents, refusing to suck up to them, positively rude to the sillier ones. A lot had defected and gone to Mrs. Haley across the valley, who charged twice as much.

“How many ponies are you taking?” she demanded.

“Six,” said Jake, walking towards the tackroom, praying she’d follow him.

“And you’ll get Mrs. Thomson to bring the head collars and the water buckets in her car. Do try to be polite for once, although I know how hard you find it.”

Jake stared at her, unsmiling. He had a curiously immobile face, everything in the right place, but without animation. The swarthy features were pale today, the full lips set in an uncompromising line. Slanting, secretive, dark eyes looked out from beneath a frowning line of brow, practically concealed by the thick thatch of almost black hair. He was small, not more than five foot seven, and very thin, a good jockey’s weight. The only note of frivolity was the gold rings in his ears. There was something watchful and controled about him that didn’t go with youth. Despite the heat of the day, his shirt collar was turned up as if against some imagined storm.

“I’ll be back tomorrow,” she said, looking down the row of loose boxes.

Suddenly her eyes lit on Africa.

“What’s she doing inside?”

“I brought her in this morning,” he lied easily. “She yells her head off if she’s separated from Dandelion and I thought you’d like a lie in.”

“Well, put her out again when you go. I’m not having her eating her head off.”

Despite the fat fee paid by Bobby Gotterel, thought Jake.

She peered into the loose box. For an appalling moment he thought she was going to peel back the rug.

“Hello, Mrs. Wilton,” shrieked Fen. “Come and look at Dandelion. Doesn’t he look smart?”

Distracted, Mrs. Wilton turned away from Africa.

“Hello, Fen, dear, you’re an early bird. He does look nice; you’ve even oiled his hooves. Perhaps you’ll bring home a rosette.”

“Shouldn’t think so,” said Fen gloomily. “Last time he ate all the potatoes in the potato race.”

“Phew, that was a near one,” said Fen, as Mrs. Wilton’s car, with the labrador’s head sticking out of the window, disappeared down the road.

“Come on,” said Jake. “I’ll make you some breakfast.”

Dressing later before he set out for the show, Jake transferred the crushed and faded yellow tansy flower from the bottom of his left gum boot to his left riding boot. Tansy warded off evil. Jake was full of superstitions. The royal gypsy blood of the Lovells didn’t flow through his veins for nothing.

2

By midday, a blazing sun shone relentlessly out of a speedwell blue sky, warming the russet stone of Bilborough Hall as it dreamed above its dark green moat. To the right on the terrace, great yews cut in the shape of peacocks seemed about to strut across the shaven lawns, down into the valley where blue-green wheat fields merged into meadows of pale silver-green hay. In the park the trees in the angelic softness of their new spring growth looked as if the rain had not only washed them but fabric conditioned them as well. Dark purple copper beeches and cochinealred may added a touch of color.

To the left, the show ring was already circled two deep with cars, and more cars in a long gleaming crocodile were still inching slowly through the main gate, on either side of which two stone lions reared up clenching red and white bunting between their teeth.

The headscarf brigade were out in full force, caught on the hop by the first hot day of the year, their arms pale in sleeveless dresses, silk-lined bottoms spilling over shooting sticks, shouting to one another as they unpacked picnics from their cars. Hunt terriers yapped, labradors panted. Food in dog bowls, remaining untouched because of the heat, gathered flies.

Beyond the cars, crowds milled round the stalls selling horsiana, moving aside to avoid the occasional competitors riding through with numbers on their backs. Children mindlessly consumed crisps, clamored for ices, balloons, and pony rides. Fathers hung with cameras, wearing creased lightweight suits smelling of mothballs, wished they could escape back to the office, and, for consolation, eyed the inevitable hordes of nubile fourteen-year-old girls, with long wavy hair and very tight breeches, who seem to parade permanently up and down at horse shows.

Bilborough Hall was owned by Sir William Blake, no relation to the poet, but nicknamed “Tiger” at school. Mingling with the crowds, he gossiped to friends, raised his hat to people he didn’t know, and told everyone that in twenty years there had only been one wet Bilborough show. His wife, a J.P. in drooping tweeds and a felt hat, whose passion was gardening, sighed inwardly at the ground already gray and pitted with hoof marks. Between each year, like childbirth, nature seemed to obliterate the full horror of the Bilborough show. She had already instructed the undergardener, to his intense embarrassment, to go around with a spade and gather up all the manure before it was trodden into the ground.

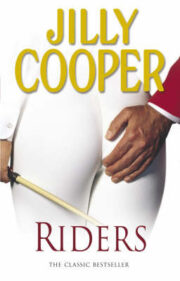

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.