“That’s lovely, Mrs. C-B,” said Charlene. “Navy goes with everything.”

Helen went white and upended the envelope. There was nothing else inside. The spotted handkerchief — Jake was telling her he wanted her for good.

“She seemed absolutely dazed,” Charlene told Dizzy afterwards.

Then Helen jumped to her feet, laughing.

“I’m going to Dublin,” she said. “I want to watch — er — my husband in the Aga Khan Cup.”

* * *

The Aga Khan Cup — a splendid trophy — is presented to the winning side in the Nations’ Cup at the Dublin Horse Show. All Dublin turns out to watch the event and every Irish child who’s ever ridden a horse dreams of being in the home team one day. For the British, it was their last chance to jump as a team before L.A. All the riders were edgy; which of the five would Malise drop? In the end it was Griselda, who pulled a groin muscle (“shafting some chambermaid,” said Rupert) but who would be perfectly recovered in time for L.A.

On the Thursday night the British team had been to one of those legendary horse-show balls. Unchaperoned by Malise (who was unwisely dining at the British Embassy) and enjoying the release from tension after being selected, they got impossibly drunk, particularly Jake, and all ended up swimming naked in the Liffey. Next day none of them was sufficiently recovered to work their horses.

Jake, who didn’t go to bed at all, spent the following morning trying to ring Helen from the press office. He had huge difficulty remembering and then dialing her number. A strange bleating tone continually greeted him. Dragging Wishbone to the telephone, he asked, “Is that the engaged or the out-of-order signal over here?”

“Sure,” said Wishbone soothingly, “ ’tis somewhere between the two.”

“Christ,” yelled Jake, then clutched his head as it nearly exploded with pain.

Half of him was desperate to talk to Helen and find out how she’d reacted to the blue spotted handkerchief he’d sent off to her the other day, when he was plastered. The other half was demented with panic at what he might have triggered off. None of the telephones seemed to work. Wishbone, who was talking to a man in a loud check suit, who seemed to know every horse in the show, bought Jake another drink.

“Drink is a terrible dirty ting,” he said happily, “but the only answer is to drink more of it.”

Jake looked at his watch and wondered if he’d ever totter as far as the ring.

“We’d better go and walk the course,” he urged Wishbone. “We’ll be very late.”

“Stop worrying,” said Wishbone. “We haven’t got a course yet.” He jerked his head towards the man in the loud check suit, who was busy buying yet another round. “He’s the course-builder.”

All in all the British put up a disgraceful performance. A green-faced tottering bunch, they staggered shakily from fence to fence, holding on to rather than checking the spreads, wincing in the blinding sunshine, to the intense glee of the merry Irish crowd, who had seen visiting teams sabotaged before.

Ivor fell off at the first and third fences, and then exceeded the time limit. Fen knocked every fence down. Rupert managed to get Rocky round with only twenty faults, his worst performance ever.

Jake, waiting to go in by the little white church, was well aware, as Hardy plunged underneath him, that the horse knew how fragile he felt.

“For Christ’s sake, get round,” said Malise, who was looking extremely tight-lipped, “or we’ll be eliminated from the competition altogether.”

Suddenly Jake looked up at the elite riders’ stand, which is known in Dublin as the Pocket. He felt his heart lurch, for there, smiling and radiant, was Helen. She was wearing a white suit, and her hair, which she’d been in too much of a hurry to wash, was tied back by a blue silk spotted handkerchief. His challenge had been taken up.

“Oh, good, Helen’s come after all,” said Malise, sounding very pleased and beetling off to the Pocket. “Good luck,” he called over his shoulder to Jake.

Concentration thrown to the winds, Jake rode into the ring. Somehow he managed to take off his hat to the judges and start cantering when the bell went, but that effort was too much for him. Hardy put in a terrific stop at the first fence and Jake went sailing through the air. The next moment Hardy had wriggled out of his bridle and was cavorting joyously round the ring until he’d exceeded the time limit.

Jake just sat on the ground, sobbing with helpless laughter. When he finally limped out of the ring Malise was looking like a thundercloud.

“There is absolutely nothing to laugh about.”

“You don’t think he’ll unselect us?” said Fen, in terror.

Jake shook his head, then winced. But all he could say to himself joyfully over and over again was, “She’s here and she’s wearing the handkerchief.”

The Irish won the Aga Khan Cup.

“There’s absolutely no point in talking to any of you,” said Malise furiously. “But I want everyone, grooms, wives, hangers-on included, to come to my room at nine o’clock tomorrow. If any of you don’t show up, you’re out.”

The only answer seemed to be to go on to another, even more riotous ball, where reaction inevitably set in.

“The hair of the dog is doing absolutely nothing to cure my hangover,” Fen grumbled to Ivor, as he trod on her toes round the dance floor. “Really, if Rupert doesn’t get his hand out of the back of that girl’s dress soon, he’ll be tickling the soles of her feet.”

The music came to an end.

“I’m going to bed.”

“Don’t,” said Ivor. “I’ll have no one to dance with.”

“Go and talk to Griselda,” said Fen, kissing him on the forehead. She couldn’t cope with the frenzied merriness. Nights like this made her longing for Dino worse than ever. She drifted rather unsteadily across the ballroom and out through one of the side doors, looking for Jake to say good night. A couple of Irishmen called out to her, trying to persuade her to come and dance, then decided not. There was something about Fen’s frozen face these days that kept men at a distance, the way Helen’s used to.

She wandered down a passage and into a dimly lit library, which was empty except for one couple. They were standing under a picture light, talking in that intense, still way of people who are totally absorbed in one another. They were about the same height. Fen’s blood ran cold. She must be seeing things.

The man was comforting the girl.

“Be patient, please, pet.”

“It was a crazy idea to come,” she said in a low voice. “I can’t bear not being able to be with you all the time or to go to bed without you tonight.”

The man was stroking her face now, drawing her close to him. “Sweetheart, just let me get Los Angeles over, and then we’ll make plans, I promise.”

“You really promise?”

“I promise. You know I love you. You’ve got the handkerchief.” He bent his head and kissed her.

Fen gave a whimper and fled. Forgetting her coat, she ran out of the building and through the streets, desperate to escape to her hotel room. Helen and Jake — it couldn’t be true. That explained why he’d been so different recently. Remote and unsociable one moment, then wildly and uncharacteristically manic the next, and terribly absentminded. He’d hardly have minded if she’d fed Desdemona caviar.

Fen had always hero-worshiped Jake and regarded his marriage to Tory as the one safe, good constant she could cling on to and perhaps one day emulate. Now her whole world seemed to be crumbling. What about Tory? What about Isa and Darklis? And more to the point, what the hell was Rupert going to do when he found out? Nothing short of murder.

55

Everyone, albeit a little pale and shaking, was on parade for Malise’s meeting next morning. No one was asked to sit down. Malise, immaculate as usual, in an olive green tweed coat and cavalry club tie, glared at them as if they were a lot of schoolboys caught smoking behind the pavilion. Yesterday’s blaze of temper had given way to a cold anger.

“At least we can go to the Games knowing we haven’t peaked yet,” he said. “I have never seen such an appalling demonstration. You rode like a bunch of fairies. I doubt if any of you had more than an hour’s sleep beforehand. You’ve made complete idiots of the selection committee.”

“Three days in the glasshouse,” muttered Rupert.

“And you can shut up,” snapped Malise. “Your round, bearing in mind the horse you were riding, was the worst of the lot. They say a lousy dress rehearsal means a good first night, but this is ridiculous.”

Then he smiled slightly, and Fen suddenly thought what a fantastically attractive man he was for his age.

“Now,” he said, “if you can find somewhere comfortable to park yourselves, I’ll show you some clips from earlier Olympics.”

Refusing a seat, Jake lounged against the door so he could look at Helen, who was sitting in one of the chairs, with Dizzy perched on the arm. She was pale and heavy-eyed, with her red hair drawn off her face and tied at the nape of the neck by the blue spotted handkerchief. To Jake, she had never looked more beautiful. He felt simply flattened by love. He could hardly concentrate on the clips of straining javelin-throwers, and sprinters crashing through the tape, and muddy three-day-eventers, and Ann Moore getting her silver.

Malise switched off the video machine.

“I don’t think I need to tell you much else. If you do get a medal, particularly a gold, it will be the greatest moment of you life, make no mistake about that. And if you don’t get that medal because you were not quite good enough on the day, or because your horse wasn’t fit, or because your nerves got to you, that’s all well and good. But if you can look back afterwards and say, I failed because I drank too much, or didn’t train or stayed up too late or didn’t work my horse diligently enough, you’ll regret it for the rest of your life.”

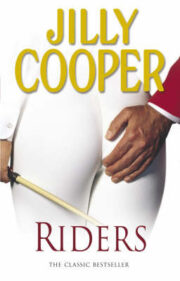

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.