“How do I know it’s all over between you and Fen?” She burst into noisy sobs.

Billy went over and hugged her.

“You’ll have to trust me; it’s you I love, always have loved. I shacked up with Fen because I was dying of loneliness, and you won’t help either of us by regurgitating her memory every five minutes.”

“I know,” sobbed Janey. “I don’t know why you put up with me.”

A new syndrome, which Billy imagined Janey’d picked up from Kev, was the mood of sweetness and light, followed by heavy drinking, followed by the hurling of abuse and china, followed by flagellating herself into a frenzy of self-abasement. Billy found it exhausting. He’d had a shattering year. He sometimes wondered if his shoulders were broad enough to carry both their problems. Holding her heaving, tearful, full-blown body, breathing in the vodka fumes, Billy looked out of the window at the Crittleden oaks, tall against a drained, blue sky, and was suddenly overwhelmed with longing for Fen, for her merriness, innocence, and kindness. She’d looked so adorable, flushed and defiant, with her wary greeny-blue kitten eyes, waiting for the other riders to turn on her. The whistling of the kettle made them both jump.

43

“How many miles to Coventry?” sighed Fen.

“Threescore miles and ten.

Will I get there by candlelight?

Yes — but don’t come back again.”

It was the last night of the three-day East Yorkshire show. Fen lay in bed with Lester the teddy bear slumped beside her, listening to the rain irritably drumming on the roof of the lorry. Sleep had evaded her again, and even the new Dick Francis had failed to distract her. She put it down and reached for her diary with the tattered photograph of Billy tucked in between September and October. He was laughing, his eyes screwed up against the Lucerne sun.

Next week was Wembley. It had been a desperate six weeks for Fen. After Crittleden, as good as their word, the British riders had sent her to Coventry. At every show she attended people who’d been her friends cut her dead or deliberately turned their backs. She knew Rupert was behind it. He’d gone out of his way to be kind to her after she’d split up with Billy, and she’d defied him publicly and humiliatingly, which had been a terrible blow to his ego. As the majority of riders were either frightened of Rupert or jealous of Fen’s meteoric rise, they were only too happy to follow his lead.

Things were not all Campbell-Black, however. Jake’s leg was mending at last; he was expected to be out of hospital soon after Wembley and riding again by the spring. And if the Crittleden victory had enraged the riders, it had enchanted the public. News of the victimization had reached the press, who were all on Fen’s side. Overnight the telephone started ringing, with newspapers, magazines, and television companies clamoring for interviews. Invitations flooded in for her to speak at dinners, open supermarkets, address pony clubs, donate various items of her clothing to raise money at charity auctions. Everywhere she was mobbed by autograph hunters. Her post was full of fan mail from admiring men and little girls, who wanted signed photographs or help with their ponies.

For a public, hungry for new idols, Fen fitted the bill perfectly. With her slender, androgynous figure with its suggestion of anorexia, jagged cabin-boy hair, and gamin, wistful, extraordinarily photogenic face, she was a true child of her time. Just as the public was drawn to Jake because he was mysteriously enigmatic, they loved Fen because she couldn’t hide her feelings. She was either furious or suicidal or ecstatic, and her naturally friendly nature endeared her to everyone.

Fen was flattered by the fame and adulation, but all her energies were centered on the horses; all she cared about was Billy.

The horses were going superbly, except for Hardy, who was growing more ungovernable. He was too strong and fly, and ever since he’d run away with her at the Royal and Lancaster early in the month, jumping right over two rows of girl guides sitting quietly by the ringside, Fen had been frightened of him, and he knew it. If he got any worse, he’d be a serious danger to Jake when he started riding again.

The horses occupied her more than full time, and it was only on the endless drives, or when she fell into bed, usually long after midnight, that she allowed herself to think of Billy.

Rumors filtered through on the groom grapevine that all was not well in the Lloyd-Foxe household. Tracey told Dizzy, who told Sarah, who told Fen, of endless rows into the night, of Janey opening Billy’s suitcase on the motorway and throwing all his clothes out of the window, because she thought he was driving too fast, of Janey storming out of a BSJA party because she heard Fen was coming, of Billy looking white and strained, and uncharacteristically snapping at the grooms.

So Fen lived on the crumbs of hope. She knew Billy would make every effort to save his marriage, but she couldn’t help counting the days to Wembley in October, when they would all be under the same roof for a week.

The following evening a very tired Billy arrived home from the Lisbon show. It was the first show to which Janey had not accompanied him since they got back together. She had stayed at home to write a piece on international polo players. At first, Billy found it a relief to be away from the rows and hysterics, but it was not long before the old demons started nagging him. He had forgiven Janey totally for going off with Kev, but he couldn’t stop the sick, churning fear which overtook him when he rang home and she wasn’t there. He hated the idea of her being closeted with handsome polo players. He remembered how she’d first interviewed him. He could hear her now: “In the last chukka, how amazing! You are brilliant, and what amazing right arm muscles. Let me feel them. You have to be so brave to play polo.”

He and Rupert had reached Penscombe as a great red September sun was falling into the beech wood. The trees had hardly started to turn, but there was already a ring of lemon-yellow leaves round the mulberry tree in the center of the yard and a wet leaf smell of autumn in the air. Having supervised the unloading and settling-down of his horses, Billy decided to walk the half-mile home through the dusk. He needed a few minutes to prepare himself for Janey. What sort of mood would she be in? Would she have missed him? Would she have ransacked his drawers, frenziedly searching for evidence? He dreaded Wembley, because Fen’s presence would trigger off more abuse.

Dew was already whitening the grass, the blue smoke from a hundred bonfires was blending with the damp vapors rising from the stream at the bottom of the valley. A blackbird was scolding as he approached the cottage; the golden dahlias in the front garden were already losing their color in the fading light. The sick feeling of menace overwhelmed him once more. There were no lights on in the cottage.

Oh God, where was she? She knew he was coming home this evening. He broke into a run, slipping on the wet leaves and the mud. He banged the gate noisily behind him. That should give the polo player a chance to leap for his breeches. He mustn’t think that. Next moment Mavis hurtled down the path, greeting him in ecstasy. The front door was open. Janey must have gone out in a hurry. Despairingly, he dropped his case on the yellow flagstones in the hall, so he had two hands free to stroke Mavis’s joyful, wriggling body.

“Billy, darling is that you?” called Janey.

Overwhelmed with relief, he could only croak out, “Yes.”

“I’m in the drawing room.”

He found her sitting at her typewriter, wearing only his sleeveless Husky and a pair of scarlet pants.

“I thought you weren’t here,” he muttered.

She got to her feet and ran to him.

“Oh, darling, I’m sorry. The piece was going so well, I couldn’t be bothered to put the light on.”

“You’ll ruin your eyes,” said Billy. “Sorry to interrupt. Why don’t you keep on working?”

“ ’Course not, now you’re back. How d’you get on?”

Billy unzipped the holdall, produced a handful of rosettes, and chucked them down on the table.

“Brilliant,” said Janey, sorting them out. “Two firsts, three seconds, a third, a fourth, and two fifths.”

“The first was the Grand Prix, and there’s lots of loot, a lovely kitchen clock and a television set and a very obscene china bull with a huge cock. I left it at Rupert’s. I’ll bring it down in the morning.”

Watching her poring over the rosettes, her breasts falling forward, strands of bush escaping from the red satin pants, Billy felt his own cock rising and wished he didn’t always want her so much. Sex had not been brilliant lately because Janey had so often fallen asleep drunk, but if they could avoid a row before they went to bed, he might get to screw her tonight.

Janey looked up, misconstruing the expression on his face.

“Sorry I look so awful, but I took Mavis for a walk in the woods at lunchtime and my trousers got drenched, so I took them off and couldn’t be bothered to find any more.”

“You look lovely.”

“I’ve been a good little wife,” Janey went on. “There’s a casserole bubbling in the oven. I’ve ironed all your shirts; not very brilliantly, I’m afraid; some of the collars curl worse than Mavis’s tail, and I’ve got your dinner jacket back from the cleaners.”

Billy was pleased she was in high spirits; then he felt a lurch of fear. The last time he’d seen her in this manic mood, floating-on-air, that inner-directed radiance that had nothing to do with him coming home, was when she was starting her affair with Kev. He desperately wanted a huge drink to blot out the terrors.

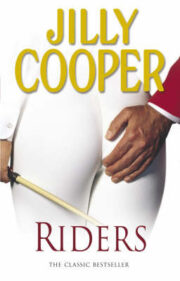

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.