Hysterical scenes followed. Janey steamed open letters, counted the Kleenex—‘Perhaps she’s used one’—examined the hairs in the bath: “That’s thicker and curlier than mine.”

“That’s pubic hair, for Christ’s sake,” said Billy.

Janey’s attitude was totally irrational. On endless occasions she had deceived him, betrayed him, made a fool of him, but it was part of her abyss of insecurity that she simply couldn’t believe that he wasn’t sloping off to see Fen when he got the chance.

Nor was it just her insane jealousy of Fen; she was paranoid about the rest of the world. What did Billy’s mother, Helen, Rupert, Malise think about her behavior? Janey liked a place in the sun and a lot of spade work would be required to win back these people’s approval.

Everyone was laying bets that the reconciliation wouldn’t last.

Fen didn’t see Billy again until the Crittleden meeting at the end of July. Rupert had warned her that Janey was coming, so in order to upset herself as little as possible, Fen arrived only just in time to walk the course for the big event, the Crittleden Gold Cup, worth £15,000 to the winner. She found the showground in an uproar. Always with an eye to publicity, Steve Sullivan, who owned Crittleden, had introduced a new fence which all the riders considered unjumpable. Called the moat, it consisted of two grassy banks. The horses were expected to clamber up the first bank, along the top and halfway down the other side, where they were expected to pop across a ditch three foot deep, on to the second bank, which they again had to scale, ride along the top, and down the other side. Here they had to jump a small, three-foot rail a couple of strides away.

Worried that all the show jumpers might load their horses up into their lorries and drive ten miles down the road to Pripley Green, where there was another big show taking place, Steve Sullivan had only put up details of the Gold Cup course an hour before the competition. When the riders saw the moat was included, all hell broke loose.

“I’m not jumping that,” said Rupert.

“Nor am I,” said Billy.

“If they jump the moat, they’ll bank the other fences,” said Ivor Braine.

“Remember the bank at Lucerne?” said Humpty. “They had an oxer immediately afterwards. All the horses treated the oxer like a bank and fell through. One of the Dutch horses had to be shot. I’m not risking Saddleback Sam.”

“That ditch is three foot deep,” said Billy. “If a horse falls in, it’ll put him off jumping water for life.”

“It’s a very gentle slope down,” protested Steve Sullivan. “It’s not slippery. They’ll jump it easily, won’t they Wishbone?” he added, appealing to the Irishman.

“Sure. I can’t see the thing giving much trouble,” said Wishbone.

“There,” said Steve. “I took my old mare across it the other night. She jumped it without turning a hair.”

“She’s due to be turned into cat food at any minute,” snapped Rupert. “Doesn’t matter if she breaks a leg. These are top-class horses. I’m not risking £100,000 for a bloody moat.”

He went off and complained to Malise, who came and examined the course.

“Seems perfectly jumpable to me; an acceptable hunting fence.”

“These aren’t hunters,” said Rupert.

Billy conferred with Mr. Block.

“I haven’t spent eight months getting Bugle right to have him smash himself up in one afternoon. D’you mind if I pull him out?”

“Do what you think best, lad,” said Mr. Block. “Don’t like the look of it myself. First hoss’ll be all right, but once the turf gets cut up, it’ll be like a greased slide in the playground.”

Steve Sullivan’s sponsors, Fuma, the tobacco giants, however, had put a lot of money into the competition and wanted a contest. The telephones were jangling in the main stand. Steve suggested putting up a big wall which the riders could jump instead, as an alternative to the moat.

“Not a fair contest,” said Rupert. “Walls aren’t the same as banks.”

“Handing it on a plate to a little horse,” said Humpty. “Little horses only need two strides between the bottom of the bank and the rail.”

Count Guy declared the moat vraiment dangereuse. Ludwig agreed: “It ees your Eenglish obsession with class, haffing a moat, Steve. Where is zee castle, zee elephant, and zee vild-life safari park?”

Steve Sullivan was sweating. He’d never faced a mutiny before. The riders were all standing grimly on the bank, hands on their hips.

Fen, meanwhile, had been quietly walking the rest of the course. It was a matt, still day, overcast but muggy, the grass very green from the recent storms. Midges danced in front of her eyes. Finally she reached the moat and stood banging her whip against her boots, looking at them in disapproval, hat pulled down over her nose.

All those grown men, including Griselda, making such a fuss, she thought. It was a tabby cats’ indignation meeting. Rupert walked up and kissed her. “Hi, angel, you’ve arrived just in time to join the picket line. We’re going to give Steve his comeuppance.”

At that moment a television minion, wearing a white peaked cap and tight pink trousers, rushed up. “Boys, boys, we simply must get started,” he cried, leaping to avoid a large pile of mud. “Motor racing’s finished, and so has the Ladies’ Singles, and they’re coming over to us at any minute.”

“Go back to your toadstool, you big fairy,” said Rupert.

“But a very rich fairy, you butch thing,” giggled the minion. “Are you going to jump, that’s what we need to know?”

The riders went into a huddle.

Fen stood slightly apart. She had caught sight of Billy. For a second they gazed at each other. He noticed how thin she’d got, her breeches far too large, her T-shirt falling almost straight down from collarbone to waist. Fen moved quickly away, stumbling into a fence, sending the wing flying. As she picked herself up, she heard Rupert say to the BBC man, “Okay, you’re on. We’ll all jump.”

Fen fled back to the collecting ring under the oak trees, where she found Desdemona being walked round by Sarah.

“What’s happening?” she asked.

“Bloody storm in a challenge cup,” said Fen. “We’re all going to jump, but, from the nasty gleam in Rupert’s eye, I know he’s up to something.”

“You’d better ring Jake.”

“No, he’s bound to tell me not to jump.”

The crowd seethed with rumor and counter-rumor. They had seen the riders gathered round the moat. This was about the most testing competition of the year. Many of them had traveled miles to watch it. The arena nearly boiled over with excitement and a huge cheer went up as Rupert, the first rider, came in. Theatrically, with much flourishing, he took off his hat to the judges and cantered the foaming, plunging, sweating Snakepit around and around, waiting for the bell which was waiting for the go-ahead from the television cameras.

He was off, bucketing over the emerald green grass, jumping superbly, clearing every fence, until he came to the moat.

“He’ll show them how to do it,” said Colonel Roxborough.

“I think not,” said Malise bleakly.

The entire riders’ stand rose to their feet, holding their breaths, as Rupert cantered up to the huge bank, then at the last moment, practically pulled Snakepit’s teeth out and cantered around it, ignoring the shouts of “wrong way,” and cantering slowly out of the ring.

There were thirty-five horses entered for the class. The next twenty riders deliberately missed out the moat, or retired before they reached it. For the first few rounds the crowd scratched their heads in bewilderment, then, as they realized they were witnessing a strike, the deliberate sabotaging of a class, the bewilderment turned to rage and they started to catcall, boo, and slow-hand clap. In the chairman’s box, with its red carpet and Sanderson wallpaper, Steve Sullivan was having a seizure.

“Bastards, bastards! All led by the nose by that fucker, Campbell-Black.”

Malise watched the spectacle with the utmost distaste.

“Behaving like a bunch of dockers and carworkers,” said Colonel Roxborough apoplectically, slowly eating his way through a bunch of grapes in a nearby Lalique bowl. “Most jump jockeys would like Bechers out of the National. They don’t go on strike.”

“Can’t you put the screws on Billy, Mr. Block?” pleaded Steve.

“I troost Billy’s joodgement when it comes to hosses,” said Mr. Block. “There’ll be another class next week.”

Malise went down to the collecting ring. Billy, having followed the other riders’ example, had just come out of the ring, to loud booing from the crowd. He avoided Malise’s eye.

Only Driffield, Ivor, and Fen, of the British riders, were left to jump.

“You’re making complete idiots of the judges and the crowd,” said Malise furiously to the British squad. “If you don’t like the course don’t jump it, but don’t resort to these gutter tactics. D’you want to kill the sport stone dead?”

With £15,000 at stake, Driffield was sorely tempted.

But then Count Guy and Ludwig both went in and retired, and who was he to argue with the experts? Dudley Diplock was in despair in the BBC commentary box. Telephones were ringing on all sides.

“Can’t we go back to tennis?” he pleaded into one receiver. “Or motor racing or cricket? There must be a county match somewhere.”

Another telephone rang. “You sit tight, Dudders,” said the sports editor. “It’s a bloody good story, the news desk have been on to say, “Be sure to interview Campbell-Black afterwards. He seems to be the ringleader.’ ”

Driffield retired.

“Your turn now, darling,” said Rupert to Fen. “Jump as far as the bank. Don’t worry about the crowd — only Italians throw bottles — and then retire. The BSJA can’t suspend all of us.”

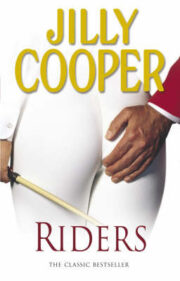

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.