All runs of luck come to an end. After a brilliant March, in which he swept the board in Antwerp, Dortmund, and Milan, Jake rolled up for the Easter meeting at Crittleden, a course which had never really been lucky for him since Sailor’s death. It had rained solidly for a fortnight beforehand and the ground was again like the Somme.

In the first big class, Macaulay, who was probably a bit tired and didn’t like jumping in a rainstorm, slipped on takeoff at the third element of the combination. Hitting the poles chest on, he somersaulted right over. Jake’s good leg was the padding between the ground and half a ton of horse. Spectators swear to this day that they could hear the sickening splinter of bones. Without treading on Jake, Macaulay managed to scramble to his feet immediately and shake himself free of the debris of wings and colored poles. Most horses would have galloped off, but Macaulay, sensing something was seriously wrong, gently nudged his master, alternately looking down at him with guilt and anguish, and then glancing over his shoulder with an indignant “Can’t you see we need help?” expression on his mud-spattered white face.

Humpty Hamilton reached Jake first.

“Come on, Gyppo, up you get,” he said jokingly. “There’s a horse show going on here.”

“My fucking leg,” hissed Jake through gritted teeth, then fainted.

He came around as the ambulance men arrived. Normally a loose horse is a nuisance at such times, but Macaulay was a comfort, standing stock-still, while Jake gripped onto his huge fetlock to stop himself screaming, looking down with the most touching concern. He also insisted on staying as close as possible, as Jake, putty-colored and biting through his lip in anguish, was bundled into an ambulance.

Fen took one look at the casualty department at Crittleden Hospital and rang Malise, who was in London.

“Jake’s done in his good leg,” she sobbed. “I don’t think a local hospital should be allowed to deal with it.”

Malise agreed and moved in, pulling strings, getting Jake instantly transferred to the Motcliffe in Oxford, where the X-rays showed the kneecap was shattered and the leg broken in five places. The best bone specialist in the country was abroad. But, realizing the fate of a national hero rested in his hands, he flew straight home and operated for six hours. Afterwards, he told the crowd of waiting journalists that he was reasonably satisfied with the result, but there might be a need for further surgery.

Tory managed to park the children, and arrived at the hospital, out of her mind with worry, just as Jake came out of the theater. For the first forty-eight hours they kept him heavily sedated. Raving and delirious, his temperature rose as he babbled on and on.

“Were any of his family in the navy?” said the ward sister, looking faintly embarrassed. “He keeps talking about a sailor.”

Tory shook her head. “Sailor was a horse,” she said.

“When can I ride again?” was his first question when he came around. Malise was a great strength to Tory. It was he and the specialist, Johnnie Buchannan, who told Jake what the future would be, when Tory couldn’t summon up the courage.

Johnnie Buchannan sat cautiously down on Jake’s bed, anxious not in any way to jolt the damaged leg, which was strapped up in the air.

“You’re certainly popular,” he said, admiring the mass of flowers and get-well cards that covered every surface of the room and were waiting outside in sackfuls still to be opened. “I haven’t seen so many cards since we had James Hunt in here.”

Jake, his face gray and shrunken from pain and stress, didn’t smile. “When can I ride again?”

“Look, I don’t want to depress you, but you certainly can’t ride for a year.”

“What?” whispered Jake through bloodless lips. “That’ll ruin me. I don’t believe it,” he went on, suddenly hysterical. “I could get up and discharge myself now.” He tried to rise off the bed and remove his leg from the hook, gave a smothered shriek, and collapsed, tears of pain and frustration filling his eyes.

“Christ, you can’t mean it,” he mumbled. “I’ve got to keep going.”

Malise got a cigarette from the packet by the bed, put it in Jake’s mouth, and lit it.

“You nearly lost the leg,” he said gently. “If it hadn’t been for Johnnie, you would never have walked again, let alone ridden. Your other leg, weakened by polio, would never have been able to support you on its own. You’ve got to get your good leg sound again.”

Jake shook his head. “I didn’t mean to sound ungrateful. It’s just that it’s my living. This’ll ruin me.”

“It won’t,” said Johnnie Buchannan. “If it knits properly, you’ll be out of here in five or six months and can conduct operations from a wheelchair at home. If you don’t play silly buggers, and take the physio side of it seriously, you could be riding again this time next year.”

Jake glared at them, determined not to betray the despair inside him. Then he shrugged his shoulders. “All right, there’s not much I can do. You’d better tell Fen to turn all the horses out. They could use the rest.”

“Isn’t that a bit extreme?” said Malise.

“No,” said Jake bleakly. “Who else can ride them?”

For a workaholic like Jake, worse almost than the pain was the inactivity. Lying in bed hour after hour, he watched the leaves slowly breaking through the pointed green buds of the sycamores and the ranks of daffodils tossing in the icy wind, and fretted. He had no resources. He was frantically homesick, missing Tory, the children, Fen and the horses, and Wolf the lurcher. The anonymity of the hospital sickeningly reminded him of the time when he had had polio as a child and his mother seldom came and visited him, perhaps feeling too guilty for never bothering to have him inoculated.

For a fastidious, reserved, and highly private person, he couldn’t bear to be totally dependent on the nurses. He was revolted by the whole ritual of blanket baths and bedpans. Lying in the same position, his leg strapped up in the air, he found it impossible to sleep. He had no appetite. He longed to see the children, but with the hospital eighty miles from home, it was difficult for Tory to bring them often; and when she did Jake was so ill and tired and weak he couldn’t cope with their exuberance for more than a few minutes, and was soon biting their heads off. He longed to ask Tory to come and look after him, but he was too proud, and anyway she had her work cut out with the children and the yard.

The Friday morning after the accident, Fen had been to see him. Such was his despair, he had been perfectly foul to her and sent her away in tears. Wracked with guilt, he was therefore not in the best of moods when Malise dropped in during the afternoon, bringing three Dick Francis novels, a biography of Red Rum, a bottle of brandy, and the latest Horse and Hound.

“You’ve made the cover,” he told Jake. “There’s an account of your accident inside. They say some awfully nice things about you.”

“Must think I’m finished,” said Jake broodingly. “Thanks, anyway.”

“I’ve got a proposal to make to you.”

“I’m married,” snapped Jake.

“It’s about Fen. If you’re grounded, why don’t you let her jump the horses?”

“Don’t be bloody ridiculous. She’s too young.”

“She’s seventeen,” said Malise. “Remember Pat Smythe and Marion Coakes? She’s good enough. What she needs is international experience.”

“I don’t want her overfaced. Anyway she’s daffy. She’d forget her own head if I wasn’t there to tell her what to do.”

“It’s not as though your horses were difficult,” said Malise. “Macaulay dotes on her. She’s ridden Laurel and Hardy, and Desdemona’s been going like a dream.”

“No,” said Jake, reaching for a cigarette.

“What is the point? You’ve brought all those horses up to peak fitness and you’ve got two grooms who need wages. Why throw the whole thing up and just lie here worrying yourself sick about money? Let her have a go. She’s your pupil. You taught her. Haven’t you got any faith in her?”

Jake shifted sideways, giving a gasp of pain.

“Pretty grim, huh?”

Jake nodded. “Can you get me a drink?”

Malise poured some brandy into a paper cup.

“It’ll give you an interest. She can ring you every night from wherever she is.”

“And where’s that going to be?”

Malise poured himself a drink, to give himself the courage to answer. “Rome. Then she can fly back for the Royal Windsor, then Paris, Barcelona, Lucerne, and Crittleden.”

“No,” said Jake emphatically.

“Why not?”

“Too young. I’m not letting a girl her age abroad by herself, with wolves like Ludwig, Guy, and Rupert around.”

“I’ll keep an eye on her. I’ll personally see she’s in bed, alone, by eleven o’clock every night. She needs a long stint abroad to give her confidence.”

“How’s she getting to Rome? In Rupert’s private jet, I suppose.”

“Griselda Hubbard’s got a lorry which takes six horses. She can easily take two or three of yours.”

“Griselda Hubbard,” said Jake, outraged. “That’s scraping the barrel.”

“Mr. Punch has turned into rather a good horse,” said Malise.

“But not with Grisel on him. Fen’s far better than her.”

“Exactly,” said Malise. “That’s why I want to take her.”

* * *

Back at the Mill House, Fen was battling with blackest gloom and trying to cheer up Macaulay. It was nearly a week since Jake’s fall, but the horse still wouldn’t settle. He wouldn’t eat and at night he walked his box. Every time a car came over the bridge, or there was a footstep in the yard, he’d rush to the half-door, calling hopefully, then turn away in childlike disappointment. Since Jake had rescued Macaulay from the Middle East they hadn’t been separated for a day. Fen had tried to turn him out with the rest of the horses, but he’d just stood shivering by the gate in his New Zealand rug, yelling to be brought in again. Poor Mac, thought Fen, and poor me too. She’d thought about Dino Ferranti so often since the World Championship, hoping so much that she’d bump into him on the circuit this summer. And now Jake had ordered the horses to be turned out, and there’d be no going abroad, and she’d be stuck with taking Desdemona to a few piffling little local shows that Jake considered within her capabilities.

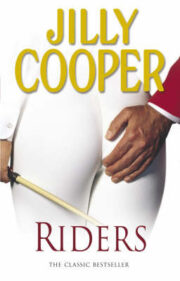

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.