“I thought Janey’d come to her senses,” said Rupert, pouring him a large drink. “Christ, if you’d have told Helen every time I’d had a bit on the side, she’d be back in America. Probably doesn’t mean a thing to Janey. She’s just a bit bored.”

“With one bounder, she was free,” said Billy miserably. “She’s been so cheerful in the last three weeks. She was so down before, I thought it was because the book was going well. It must have been Kevin. What the hell do I do?”

“Punch him on the nose.”

“I can’t, at £50,000 a year. Very expensive bloody nose.”

“Find another sponsor.”

“Not so easy. I’m not the bankable property I was two years ago.”

“Rubbish. You’re just as good a rider. You’ve just lost your nerve.” Rupert looked at his watch, “Aren’t you supposed to be making a speech in London?”

Billy went white, “I can’t.”

“You bloody well can. Don’t want to go ratting on that. They’ll say you’ve really lost your nerve. I’ll drive you up.”

Billy somehow survived the lunch and making his speech. Paranoid now, he imagined all the audience there looking at him curiously, wondering how he was coping with being cuckolded. The journalist in the front row had a copy of Private Eye in his pocket.

Even worse, that evening he and Janey had to go to some dreadful dance at Kev’s golf club in Sunningdale. Billy didn’t say anything to Janey. He had a faint hope, as he had when he was a child, that if he kept quiet and pulled the bedclothes over his head, the nasty burglar might assume he was asleep and go away. Janey, he noticed, didn’t grumble at all about going, as she would have done once, and looked absolutely ravishing in plunging white broderie anglaise.

She was easily the most beautiful woman in the room. All the men were gazing at her and nudging Kev for an introduction. Billy wondered how many of them had read Private Eye, and proceeded to get drunk.

Enid Coley was made of sterner stuff. Having tried to fill up Janey’s cleavage with an orchid and maidenhair fern wrapped in silver paper, which Janey rudely refused to wear, she waited for a lull in the dancing. Then she walked up to Janey, holding a glass of wine as though she was going to shampoo her hair, and poured it all over Janey’s head.

“What the hell d’you think you’re doing?” demanded Billy.

“Ask her what she’s been doing,” hissed Enid. “Look in my husband’s wallet, and you’ll see a very nice picture of your wife. Since you’ve been away she’s been seducing my husband.”

“Shut up, you foul-mouthed bitch.”

“Don’t talk to me like that. If you weren’t so drunk all the time, you might have done something to stop it.”

Taking Janey, dripping and speechless, by the hand, Billy walked straight out of the golf club. It was not until they were ten miles out of Sunningdale that she spoke. “I’m sorry, Billy. When did you know?”

“I read Private Eye at the station.”

“Oh, my God. Must have been terrible.”

“Wasn’t much fun.”

“Beastly piece, too. I wasn’t sacked. I resigned. Kev, in fact, was rather chuffed. He’s never been in Private Eye before.”

Billy stopped the car. In the light from the streetlamp, Janey could see the great sadness in his eyes.

“Do you love him?”

“I don’t know, but he’s so macho and I’m so weak. I guess I need someone like him to keep me on the straight and narrow.”

“He’s hardly been doing that recently,” said Billy. “Look, I love you. It’s my fault. I shouldn’t have left you so much, or let us get into debt, or been so wrapped up in the horses. It must have been horrible for you, with no babies, and struggling to write a book on no money. I’ll get some money from somewhere, I promise you. I just don’t want you to be unhappy.”

On Monday, Kevin Coley summoned Billy. “I’ve had a terrible weekend. I haven’t slept a wink for worrying,” were his opening words.

“I’m so sorry. What on earth’s the trouble?” asked Billy.

“I knew I had to break the news to you that I can’t go on sponsoring you. My only solution is to withdraw.”

“Pity your father didn’t do that forty years ago,” said Billy.

Kevin missed the joke; he was too anxious to say his piece. “The contract runs out in October and I’m not going to renew it. You haven’t won more than £3,000 in the last six months. I’m losing too much money.”

“And fucking my wife.”

“That has nothing to do with it.”

“Then I tried to hit him,” Billy told Rupert afterwards, “but I was so pissed I missed. He’s talking of sponsoring Driffield.”

“Oh, well,” said Rupert, “I suppose one good turd deserves another.”

Winning the World Championship had transformed Jake Lovell into a star overnight. Wildly exaggerated accounts of his gypsy origins appeared in the papers. Women raved about his dark, mysterious looks. Young male riders imitated his deadpan manner, wearing gold rings in their ears and trying to copy his short, tousled hairstyle. Gradually he became less reticent about his background and admitted openly that his father had been a horsedealer and poacher and his mother the school cook. Sponsors pursued him, owners begged him to ride their horses. His refusal to turn professional, his extreme reluctance to give interviews (I’m a rider, not a talker) all enhanced his prestige. The public liked the fact that his was still very much a family concern, Tory and the children helping out with the horses. Fen, under Malise’s auspices, won the European Junior Championship in August, and, although still kept in the background by Jake, was beginning to make a name for herself.

Most important of all, Jake had given a shot in the arm to a sport that, in Britain, had been losing favor and dropping in the ratings. The fickle public like heroes. The fact that Gyppo Jake had trounced all other nations in the World Championship dramatically revived interest in show jumping.

Wherever Jake jumped now, he was introduced as the reigning World Champion, which was a strain, because people expected him to do well, but also increased his self-confidence. For the rest of the year, and well into the spring, he and Macaulay stormed through Europe like Attila the Hun, winning every grand prix going. Two of his other novices, Laurel and Hardy, had also broken into the big time. Laurel, a beautiful, timid, highly strung bay who started if a worm popped its head out of the ground in the collecting ring, was brilliant in speed classes. Hardy, a big cobby gray, was a thug and a bully, but had a phenomenal jump. Both were horses the public could identify with.

But it was Macaulay they really loved. While other riders changed their sponsors and were forced to call their horses ridiculous, constantly changing names, Macaulay remained gloriously the same, following Jake around without a lead like a big dog, nudging whoever presented the prizes and responding with a succession of bucks to the applause of the crowd.

In November, Jake was voted Sportsman of the Year. Macaulay came to the studios with him and exceled himself by sticking out his cock throughout the entire program, treading firmly on Dudley Diplock’s toe, and eating the scroll that was presented to his master. For the first time, the public saw Jake convulsed with laughter and were even more enchanted.

Enraged by his humiliation in the World Championship, and the appalling publicity he received over selling Macaulay to the Middle East, Rupert decided to up sticks for a couple of months. Loading up six of his best horses, he crossed the Atlantic and boosted his morale by winning at shows in Calgary, Toronto, Washington, and Madison Square Garden.

Helen had always sighed wistfully that her parents had never had the opportunity to get to know their grandchildren. Rupert took her at her word. Flying the whole family out, plus the nanny, he dumped them in Florida with Mr. and Mrs. Macaulay, while he traveled the American circuit and “enjoyed himself,” as Mrs. Macaulay pointed out sourly. Staying with her parents with the two children shattered one of Helen’s illusions. Even if things got too bad with Rupert, she could never run home to Mummy anymore. The whole family were glad to get back to Penscombe in November.

* * *

Two weeks after Rupert left for America, Billy had gone on a disastrous trip to Rotterdam, where he had fallen off, paralytically drunk, in the ring and sat on the sawdust, laughing, while one of his only remaining novices cavorted round the ring, refusing to be caught. The English papers had been full of the story. Billy got home to find that Janey had walked out, taking all her clothes, her manuscript, Harold Evans and, worst of all, Mavis. Billy had stormed drunkenly round to the flat, where she was living with Kev, and tried to persuade her to come back. She had goaded him so much, and become so hysterical, that finally he’d blacked her eye and walked out with Mavis under his arm.

A week later he received an injunction from Janey’s solicitors accusing him of violent behavior and ordering him to stay away. Next day, The Bull, who’d been lackluster and off form for weeks, had a blood test. Not only was he anemic but had picked up a virus, said the vet, and should not be jumped for three months.

Billy took refuge in the bottle, selling off his novices and pieces of furniture to quiet his creditors, and to buy more whisky, refusing to see anyone. He also sacked Tracey, because he couldn’t afford to pay her anymore. She refused to go. No one else could be permitted to look after The Bull. She’d live on her dole money, she said, and wait until Billy got his form back.

Rupert was shattered, when he got home, to find Billy in such a state. Typically, whenever he’d spoken to Rupert on the telephone from America, Billy had pretended things were all right and he and Janey were ticking along. Now, sitting in a virtually empty cottage, surrounded by empty bottles, he had gone gray and aged ten years. Immediately, Rupert set about a process of, as he called it, re-hab-Billy-tation, ordering Helen to get Billy’s old room ready at Penscombe, packing Billy off to an alcoholics’ home to dry out, and searching for a new sponsor.

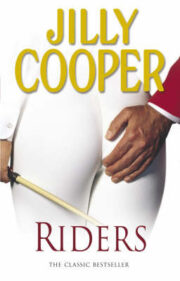

"Riders" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Riders". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Riders" друзьям в соцсетях.