“Then it’s important to me,” I say. “It might take months, a year or two even, to gather all of the information we need, all of the resources, but we’ll get it done. And we’ll do it together. But you have to promise me that you’ll be patient and that you’ll—”

“I give you my word,” she cuts in. “I don’t care how long it takes. And I’ll follow your lead and your instructions every step of the way. I’m not going to make the same mistakes again.”

Soon after our conversation on the patio, I take Sarai into the bath and I wash her hair as she sits between my legs in the tub.

We talk for the longest time about life the way it was before. About her time growing up with her mother, before her mother found drugs and men. When she used to sit curled next to her watching Saturday morning cartoons. We talk about my life before I was taken by the Order. About how I used to play Dosenfussball (‘tag’) and Verstecken (‘kick the can’) with Niklas when I was six-years-old back in Germany.

We get so lost in the memories of when our lives were so much simpler, so innocent, that for a long time we both forget how things are now.

I also forget, just for a moment, that things between us are still not set in stone.

And that they might never be.

Sarai

Victor is gone when I wake up the next morning, his side of the bed empty and cold. I crush his pillow against my chest and hold it close to me. He had an eight o’clock appointment with a contact in Bernalillo. He wanted me to go along with him, but I’m quite exhausted by travel, especially when it doesn’t involve a plane.

Since the Krav Maga studio location has been ‘compromised’, as Victor calls it, he feels it’s best that we move from New Mexico as soon as possible. My goal for the day is to pack as much of the house as I can, though that shouldn’t be too difficult since Victor’s closets and such are devoid of the average person’s daily living. He doesn’t have a ‘junk drawer’ where he tosses miscellaneous items that will sit there unused for a lifetime. His closets are not cluttered with old shoe boxes and stacks of keep-just-in-case paperwork, or clothes that he hasn’t worn in five years. The cabinets in his kitchen aren’t stocked with expensive matching dishes that only get taken out of their neat little spot on holidays and special occasions. There are no family portraits hanging in a neat line on the walls down the hallway, or keepsake items sitting on a shelf given to him by important people which he can’t bear to part with for sentimental reasons. A few boxes should do it. His suits. My growing collection of clothes and wigs and jewelry and makeup and plethora of shoes. Looks like I’m mostly packing my own stuff.

I press the Power button on the remote and the flat screen television in the living room hums to life. I leave it on one of the national news stations for background noise. The sun beams through the glass door which frames the New Mexico landscape behind the house. I stare out at it for only a moment, feeling like I need a change of scenery. After spending most of my life in Mexico, surrounded by sand and thin trees and dried grass and heat…well, I’m glad to be moving. Victor said the new house will either be in Washington or New York. Either is fine with me, both of them a stark difference from what I’m used to.

I’ll know for sure tomorrow.

I make a small breakfast of a scrambled egg and a single slice of wheat toast and wash it down with a glass of milk. I do my morning workout and then take a quick shower, afterwards, slipping on a pair of black cotton shorts and a tight black cotton top. I pull my hair into a ponytail and slip my fingers between two halves, pulling it tight against my scalp. Standing in front of the enormous bathroom mirror, I start to put on makeup, but decide I’m too lazy to mess with it right now, and I go back to packing. As I’m taking Victor’s suits down from the closet, one by one, and securing them in tall, zippered garment bags, I feel something underneath my hand as I’m patting a sleeve down neatly against the jacket breast. I move the sleeve away, setting it against the bed and then open the jacket. I slip my hand into the inside pocket and grasp a small envelope in my fingers. It feels somewhat thick, about half an inch.

Before I pull it from the pocket all the way, for a moment I start to put it back, my conscience telling me that it’s none of my business. But I look anyway.

The envelope is old and worn, with thinly tattered edges and a yellow-brown discoloration. It’s a small envelope, more square than rectangular, and probably held a birthday card or an invitation at some point. There are photographs inside. Old photographs. I pull the flap from inside the envelope and open it the rest of the way, taking the small stack into my hand. The photograph on top is of a man, with light hair and a strong jawline. He’s wearing a white shirt with a maroon tie. He’s sitting in a leather chair surrounded by walls covered in tacky tapestry wallpaper. A young brown-haired boy and an even younger girl with white-blonde hair stand on either side of him, smiling widely for the camera.

The next photograph is of the same young boy and girl, posing with a beautiful woman with long, blonde flowing hair, outside in what appears to be a park.

All of the photos are aged, with a brown-orange tint and cracks running along the edges where they had been bent over the years. I flip each one over and read the backs. Versailles 1977, Paris 1977, Versailles 1976, scribbled in the left-hand corners and almost unreadable as the ink has begun to fade. In the next few photos the boy is older, maybe seven or eight, and he’s standing with his arm draped over the shoulder of another boy. München 1981, Berlin 1982. My heart sinks when I realize that all of these photos are of Victor and Niklas and who I believe to be their father and Victor’s mother. The girl must be a sister.

It breaks my heart to know that he carries these around with him like this. It’s further proof that Victor is not emotionless, that deep inside of him is a man who has been hidden from the world, who has been forced to carry around the only memories of his childhood inside a pocket.

It’s proof that he’s human, a lost, emotionally damaged human that I want so desperately to restore.

My head snaps around when I hear footsteps inside the house.

I drop the photos on the bed and grab the 9MM from the bedside table, releasing the magazine into my hand to check that it’s full. I pop it back inside the gun and rush quietly across the room in my bare feet, pushing my back against the wall, and walk alongside it toward the door. I keep the gun fixed at head-level, gripped in both hands, and stop at the door to listen. Nothing. At least, I hear nothing but the damned television that I’m wishing I had never turned on.

I begin to think it could just be Fredrik, but I’m not taking any chances.

With my back still against the wall, I move around the doorframe and step into the hallway when I see that it’s clear. A shadow moves against the terra cotta tile floor at the far end of the hall and I freeze in my steps. I feel my heart drumming in the tips of my fingers, itching to put all of my force on that trigger. I remain still, the back of my neck breaking out in beads of sweat, and I watch the floor for a long moment without allowing myself to blink for fear of missing anymore movement. When I hear the footsteps again, farther away this time, I move stealthily down the length of the hallway on the pads of my feet.

Approaching the end, I stop feet from the corner and take a deep breath into my lungs. I let it out slowly, quietly, and then listen again. The voices of the people on the news carrying on and on about ‘Obamacare’ grates on my nerves as it only helps to drown out any voices or footsteps I might be able to hear, and from which direction they might be coming from.

Finally, I do hear voices, whispering:

“Check the rooms,” I hear a man say. “She’s probably hiding underneath a bed or inside a closet.”

No, asshole, I’m waiting for you to come walking down the hallway so I can put a bullet in your face.

A man in a black suit rounds the corner with a gun in his hand and I squeeze a shot off the second he appears at the end of the hall. The shot rings out, vociferous in my ears, and the man falls against the floor, blood spewing from the bullet wound in the side of his neck. He gasps and chokes, trying to cover the wound with both of his hands now covered in blood.

I step around his body, ignoring the unsettling gurgling sounds that he makes and round the corner firing off three more shots. I manage to hit one more man before a white-hot pain sears through the back of my head. As I’m going down, I see the second man that I shot going down with me out ahead. And I see Stephens, standing next to his dead body in all of his tall, brooding glory. My gun is no longer in my hands and I’m so disoriented by whatever just made contact with the back of my head that it takes me a moment to realize I’m lying on the cool floor with my cheek pressed against a crevice in the tile. I reach back to feel my head and there is blood on my fingers when I touch my hair.

Stephens crouches beside me, a menacing grin etching deep lines around his hard mouth. His salt and pepper hair appears darker, his height, taller, the chasm of a dimple in the center of his chin, deeper. He peers down at me, propping both elbows on the tops of his thighs, his big hands hanging freely between them, the right wrist dressed in a thick gold watch. He smells strongly of cologne and cigars.

“You’re a hard girl to find,” Stephens says.

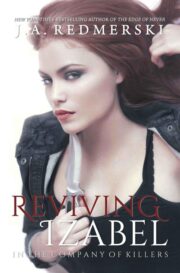

"Reviving Izabel" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Reviving Izabel". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Reviving Izabel" друзьям в соцсетях.