Michael wasted no more time. He put the car in gear and began pulling out from the parking lot before I even had time to remove my hand.

"Great," he said. His voice was maybe a little uneven, so he cleared his throat, and said, with a little more dignity, "I mean, that sounds all right."

A few seconds later, we were cruising along the Pacific Coast Highway. It was only ten o'clock or so, but there weren't many other cars on the road. It was, after all, a weeknight. I wondered if Michael's mother, before he'd left the house, had told him to be home at a certain time. I wondered if, when he didn't come home by curfew, she'd worry. How long, I wondered, would she wait before calling the police? The hospital emergency rooms?

"So nobody," Michael said as he drove, "was really hurt, right? In the accident?"

"No," I replied. "No one was hurt."

"That's good," Michael said.

"Is it?" I pretended to be looking out the passenger side window. But really I was watching Michael's reflection.

"What do you mean?" he asked quickly.

I shrugged. "I don't know," I said. "It's just that … well, you know. Brad."

"Oh." He gave a little chuckle. There wasn't any real humor in it, though. "Yeah. Brad."

"I mean, I try to get along with him," I said. "But it's so hard. Because he can be such a jerk sometimes."

"I can imagine," Michael said. Pretty mildly, I thought.

I turned in my seat so that I was almost facing him.

"Like, you know what he said tonight?" I asked. Without waiting for a reply, I said, "He told me he was at that party. The one where your sister fell. You know. Into the pool."

I do not think it was my imagination that Michael's grip on the wheel tightened. "Really?"

"Yeah. You should have heard what he said about it, too."

Michael's face, in profile to mine, looked grim.

"What did he say?"

I toyed with the seatbelt I'd fastened around myself. "No," I said. "I shouldn't tell you."

"No, really," Michael said. "I'd like to know."

"It's so mean, though," I said.

"Tell me what he said." Michael's voice was very calm.

"Well," I said. "All right. He basically said - and he wasn't quite as succinct as this, because, as you know, he's pretty much incapable of forming complete sentences - but basically he said your sister got what she deserved because she shouldn't have been at that party in the first place. He said she hadn't been invited. Only popular people were supposed to be there. Can you believe that?"

Michael carefully passed a pickup truck. "Yes," he said quietly. "Actually, I can."

"I mean, popular people. He actually said that. Popular people." I shook my head. "And what defines popular? That's what I'd like to know. I mean, your sister was unpopular why? Because she wasn't a jock? She wasn't a cheerleader? She didn't have the right clothes? What?"

"All of those things," Michael said in the same quiet voice.

"As if any of that matters," I said. "As if being intelligent and compassionate and kind to others doesn't count for anything. No, all that matters is whether you're friends with the right people."

"Unfortunately," Michael said, "that oftentimes appears to be the case."

"Well," I said. "I think it's crap. I said so, too. To Brad. I was like, 'So all of you just stood there while this girl nearly died because no one invited her in the first place?' He denied it, of course. But you know it's true."

"Yes," Michael said. We were driving along Big Sur now, the road narrowing while, at the same time, growing darker. "I do, actually. If my sister had been … well, Kelly Prescott, for instance, someone would have pulled her out at once, rather than stand there laughing at her as she drowned."

It was hard to see his expression since there was no moon. The only light there was to see by was the glow from the console in the dashboard. Michael looked sickly in it, and not just because the light had a greenish tinge to it.

"Is that what happened?" I asked him. "Did people do that? Laugh at her while she was drowning?"

He nodded. "That's what one of the EMS guys told the police. Everybody thought she was faking it." He let out a humorless laugh. "My sister - that was all she wanted, you know? To be popular. To be like them. And they stood there. They all just stood there laughing while she drowned."

I said, "Well. I heard everyone was pretty drunk." Including your sister, I thought, but didn't say out loud.

"That's no excuse," Michael said. "But of course nobody did anything about it. The girl who had the party - her parents got a fine. That's all. My sister may never wake up, and all they got was a fine."

We had reached, I saw, the turn-off to the observation point. Michael honked before he went around the corner. No one was on the other side. He swung neatly into a parking space, but he didn't switch off the ignition. Instead, he sat there, staring out into the inky blackness that was the sea and sky.

I was the one who reached over and turned the motor off. The dashboard light went off a second later, plunging us into absolute darkness.

"So," I said. The silence in the car was pretty deafening. There were no cars on the road behind us. If I opened the window, I knew the sounds of the wind and waves would come rushing in. Instead, I just sat there.

Slowly, the darkness outside the car became less consummate. As my eyes adjusted to it, I could even make out the horizon where the black sky met the even blacker sea.

Michael turned his head. "It was Carrie Whitman," he said. "The girl who had the party."

I nodded, not taking my gaze off the horizon. "I know."

"Carrie Whitman," he said again. "Carrie Whitman was in that car. The one that went off the cliff last Saturday night."

"You mean," I said quietly, "the car you pushed off the cliff last Saturday night."

Michael's head didn't move. I looked at him, but I couldn't quite read his expression.

But I could hear the resignation in his voice.

"You know," he said. It was a statement, not a question. "I thought you might."

"After today, you mean?" I reached down and undid my seatbelt. "When you nearly killed me?"

"I'm so sorry." He lowered his head, and finally, I could see his eyes. They were filled with tears. "Suze, I don't know how I'll ever - "

"There was no seminar on extraterrestrial life at that institute, was there?" I glared at him. "Last Saturday night, I mean. You came out here, and you loosened the bolts on that guardrail. Then you sat and waited for them. You knew they'd come here after the dance. You knew they'd come, and you waited. And when you heard that stupid horn, you rammed them. You pushed them over the side of that cliff. And you did it in cold blood."

Michael did something surprising then. He reached out and touched my hair where it curled out from beneath the knit watch cap I was wearing.

"I knew you'd understand," he said. "From the moment I saw you, I knew you, out of all of them, were the only one who'd understand."

I seriously wanted to throw up. I mean it. He didn't get it. He so didn't get it. I mean, hadn't he thought about his mother at all? His poor mother, who had been so excited because a girl had called him? His mother, who already had one kid in the hospital? Hadn't he thought how his mother was going to feel when it came out that her only son was a murderer? Hadn't he thought about that at all?

Maybe he had. Maybe he had, and he thought she'd be glad. Because he'd avenged what had happened to his sister. Well, almost, anyway. There were still a few loose ends in the form of Brad … and everyone else who'd been at that party, I suppose. I mean, why just stop at Brad? I wondered how he'd managed to secure the guest list, and if he intended to kill everyone on it or just a select few.

"How did you know, anyway?" he asked in what I suppose he meant to be this tender voice. But all it did was make me want to throw up even more. " About the guardrail, I mean? And their car horn. That wasn't in the papers."

"How did I know?" I jerked my head from his reach. "They told me."

He looked a little hurt at my pulling away from him. "They told you? Who do you mean?"

"Carrie," I said. "And Josh and Felicia and Mark. The kids you killed."

His hurt look changed. It went from confused, to startled, and then to cynical, all in a matter of seconds.

"Oh," he said with a little laugh. "Right. The ghosts. You tried to warn me about them before, didn't you? Right here, as a matter of fact."

I just looked at him. "Laugh all you want," I said. "But the fact is, Michael, they've been wanting to kill you for a while now. And after the stunt you pulled today with the Rambler, I am seriously thinking about letting them."

He stopped laughing. "Suze," he said. "Your strange fixation with the spirit world aside, I told you: today was an accident. You weren't supposed to be in that car. You were supposed to ride home with me. Brad was the one. Brad was the one I wanted dead, not you."

"And what about David?" I demanded. "My little brother? He's twelve years old, Michael. He was in that car. Did you want him dead, too? And Jake? He was probably delivering pizzas the night your sister was hurt. Should he die for what happened to her? Or my friend Gina? I guess she deserves to die, too, even though she's never even been to a party in the Valley."

Michael's face was white against the bits of sky I could see through the window behind his head.

"I didn't mean for anyone to get hurt," he said, in an oddly toneless voice. "Anybody except for the guilty, I mean."

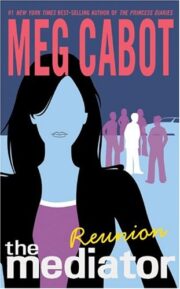

"Reunion" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Reunion". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Reunion" друзьям в соцсетях.