My mother looked at him curiously. "Actually," she said, "that's not what I was thinking."

I knew what was coming. My mom has a memory like a steel trap. She needs it, of course, in her line of work. But I knew it was only a matter of time before she figured out where she'd heard Michael's name before.

"He was the one who was in that accident this weekend," I said, to hasten the inevitable. "The one where those four RLS students were killed."

Dopey dropped his fork. It made quite a clatter as it landed on his plate.

"Michael Meducci?" He shook his head. "No way. That was Michael Meducci? You are shitting me."

Andy said, sharply, "Brad. Language, please."

Dopey said, "Sorry," but his eyes, I noticed, were very bright. "Michael Meducci," he said again. "Michael Meducci killed Mark Pulsford?"

"He didn't kill anybody," I snapped. I could see I should have kept my mouth shut. Now it was going to be all over school. "It was an accident."

"Really, Brad," Andy said. "I'm sure the poor boy didn't mean to kill anyone."

"Well, I'm sorry," Dopey said. "But Mark Pulsford was like one of the best quarterbacks in the state. Seriously. He had a scholarship to UCLA, the whole thing. That guy was really cool."

"Oh, yeah? Then what was he doing hanging around you?" Sleepy, in a rare moment of wit, grinned at his brother.

"Shut up," Dopey said. "We happen to have partied together."

"Right," Sleepy said with a sneer.

"We did," Dopey insisted. "Last month, in the Valley. Mark was the bomb." He grabbed a roll, stuffed most of it into his mouth, then said around the doughy mass, "Until Michael Meducci came along and murdered him, that is."

I noticed that Gina was observing me with one eyebrow - one only - raised. I ignored her.

"The accident wasn't Michael's fault," I said. "At least, he hasn't been charged with anything."

My mother laid down her own fork. "The investigation into the accident," she said, "is still ongoing."

"As many accidents as they've had," my stepfather said as he rolled a few spears of asparagus onto my mother's plate, then passed the platter of them to Gina, "on that section of highway, you would think somebody would do something to improve the road conditions."

"The narrow stretch of highway," Doc said conversationally, "along the one-hundred-mile stretch of seacoast known as Big Sur has traditionally been considered treacherous - even highly dangerous. Frequently enshrouded with coastal fog, this winding and narrow mountainous road is, thanks to historical preservationists, unlikely to be expanded. The very isolation of the area is what has held such appeal for the many poets and artists who have made their homes there, including Robinson Jeffers, who found the splendor of the bleak wilderness highly appealing."

I blinked at my youngest stepbrother. His photographic memory could, at times, be annoying, but for the most part it was highly useful, particularly when term paper time came rolling around.

"Thanks," I said, "for that."

Doc smiled, revealing a mouthful of food-encrusted braces. "Don't mention it."

"The worst part of it," Andy said, continuing his rant on the safety conditions on Highway 1, "is that young drivers seem irresistibly drawn to that particular stretch of road."

Dopey, shoveling wild rice into his mouth as if it were the first food he'd seen in weeks, snickered and said, "Well, duh, Dad."

Andy looked at his middle-born son. "You know, Brad," he said mildly. "In America - and, I'm told, much of Europe - it is considered socially acceptable to occasionally lay down our fork between bites, and spend some time actually chewing."

"That's where the action is," Dopey said, laying down his fork as his father had suggested, but compensating by speaking with his mouth full.

"What action?" my stepfather asked curiously.

Sleepy, who generally didn't speak unless absolutely forced to, had grown almost garrulous since Gina's arrival. "He means the Point," Sleepy said.

My mother looked confused. "The point?"

"The Point," Sleepy corrected her. "The observation point. It's where everybody goes to make out on Saturday night. At least" - Sleepy chuckled to himself - "Brad and his friends."

Dopey, far from taking offense at this slanderous remark, waved an asparagus spear as if it were a cigar while he explained, "The Point is the bomb."

"Is that," Doc asked interestedly, "where you take Debbie Mancuso?" and then he winced in pain as one of his shins was brutally assaulted beneath the table. "Ow!"

"Debbie Mancuso and I are not going out!" Dopey bellowed.

"Brad," Andy said. "Do not kick your brother. David, do not invoke Miss Mancuso's name at the dinner table. We've talked about this. And Suze?"

I looked up with raised eyebrows.

"I don't like the idea of you getting into a car with a boy who was involved in a fatal accident, whether it was his fault or not." Andy looked at my mother. "Do you agree?"

"I'm afraid I'm going to have to," my mother said. "I feel bad about it. The Meduccis have certainly been through some trying times lately - " When my stepfather looked at her questioningly, my mother said, "Their little girl was the one who almost drowned a few weeks ago. You remember."

"Oh." Andy nodded. "At that pool party. There was no parental supervision - "

"And plenty of alcohol," my mother said. "Poor thing apparently drank too much and fell in. Nobody noticed - or if they did, nobody did anything about it. Not until it was too late. She's been in a coma ever since. If she lives, it will be with severe brain damage. Suze." My mother laid down her fork. "I don't think it's a good idea for you to be seeing this boy."

Ordinarily, this would have cheered me up considerably. I mean, I wasn't exactly looking forward to going out with the guy.

But I sort of had to. I mean, if I was to have any hope at all of keeping him from slipping into a nerd coffin.

"Why?" I carefully swallowed a mouthful of salmon. "It's not Michael's fault his sister's an alcoholic who can't swim. And what were her parents thinking, anyway, letting an eighth grader go to a party like that?"

"That," my mother said, her mouth tightening, "is not the issue here, and you know it. You're just going to have to call that young man and tell him that your mother absolutely forbids you to get into a vehicle with him. If he wants to come here and spend the evening with you watching videos or whatever, that's fine. But you are not getting into a car with him."

My eyes widened. Here? Spend the evening here? Under Jesse's watchful eye? Oh, God, just what I needed. The image these words conveyed filled me with such horror, the forkful of salmon I'd had poised before my lips fell into my lap, where it was instantly vacuumed up by a long canine tongue.

My mother touched my hand. "Suze," she said softly. "I really mean it. I don't want you getting into a car with that boy."

I looked at my mother curiously. It's true that in times past I have been forced to disobey her, largely due to circumstances beyond my control. But she didn't know that. That I had disobeyed her, I mean. For the most part, I'd managed to keep my transgressions to myself - except for the occasions I'd been brought home by the police, incidents so few they are hardly worth mentioning.

But since that had not been the case in this situation, I didn't quite understand why she felt it necessary to repeat her edict concerning Michael Meducci.

"Okay, Mom," I said. "I got it the first time."

"It's just something I feel very strongly about," she said.

I looked at her. It wasn't that she appeared … well, guilty. But she definitely knew something. Something she wasn't letting on.

This was not particularly surprising. A television journalist, my mother was often privy to information not necessarily meant for release to the public. She wasn't one of those reporters you hear about, either, who'd do anything to get the "big" story. If a cop told my mother something - and they often do; my mother, even though she's forty-something, is still pretty hot, and just about anybody would tell her anything she wanted to know if she licked her lips enough - he could depend on her not mentioning it on air if he asked her not to. That's just how she is.

I wondered what, exactly, she knew about Michael Meducci and the accident that had killed the four Angels.

Enough, apparently, to keep her from wanting me to hang around with him.

I didn't exactly think she was being particularly unfair to him, either. I couldn't help remembering what Michael had said in the car, right before pulling back out onto the highway: They were just taking up space.

Suddenly, I didn't blame those kids so much for trying to drown him.

"Okay Mom," I said. "I get it."

Apparently satisfied, my mother turned back to her salmon, which Andy had grilled to perfection and served with a delicate dill sauce.

"So how are you going to break it to him?" Gina asked a half hour later as she helped me load the dishwasher after dinner - having brushed aside my mother's insistence that, as a guest, she did not have to do this.

"I don't know," I said hesitantly. "You know, the whole Clark Kent thing aside - "

"Geeky on the outside, dreamy in the middle?"

"Yeah. In spite of that - which is hard to resist, believe me - he's still kind of got this quality that strikes me as…"

"Stalkery?" Gina said, rinsing the salad bowl before handing it to me to put in the dishwasher rack.

"Maybe that's it. I don't know."

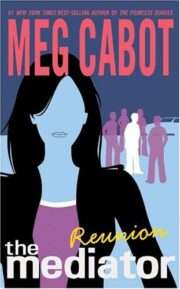

"Reunion" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Reunion". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Reunion" друзьям в соцсетях.