“No,” said Judith. “Nothing of the sort. This—gentleman—constrained me to ride in his carriage, that is all.”

“Constrained you!” Peregrine took a hasty step forward.

She was sorry to have said so much, and added at once: “Do not let us be standing here talking about it! I think he is mad.”

The gentleman gave his low laugh, and produced a snuffbox from one pocket, and held a pinch first to one nostril and then to the other.

Peregrine advanced upon him, and said stormily: “Sir, I shall ask you to explain yourself!”

“You forgot to tell him that I kissed you, Clorinda,” murmured the gentleman.

“What?” shouted Peregrine.

“For heaven’s sake be quiet!” snapped his sister.

Peregrine ignored her. “You will meet me for this, sir! I hoped I might come upon you again, and I have. And now to find that you have dared to insult my sister. You shall hear from me!”

A look of amusement crossed the gentleman’s face. “Are you proposing to fight a duel with me?” he inquired.

“Where and when you like!” said Peregrine.

The gentleman raised his brows. “My good boy, that is very heroic, but do you really think that I cross swords with every country nobody who chooses to be offended with me?”

“Now, Julian, Julian, what are you about?” demanded a voice from the doorway into the coffee-room. “Oh, I beg pardon, ma’am! I beg pardon!” Lord Worcester came into the hall with a glass in his hand, and paused, irresolute.

Peregrine, beyond throwing him a fleeting glance, paid no heed to him. He was searching in his pocket for a card, and this he presently thrust at the gentleman in the greatcoat. “That is my card, sir!”

The gentleman took it between finger and thumb, and raised an eyeglass on the end of a gold stick attached to a ribbon round his neck. “Taverner,” he said musingly. “Now where have I heard that name before?”

“I do not expect to be known to you, sir,” said Peregrine, trying to keep his voice steady. “Perhaps I am a nobody, but there is a gentleman who I think—I am sure—will be pleased to act for me: Mr. Henry Fitzjohn, of Cork Street!”

“Oh, Fitz!” nodded Lord Worcester. “So you know him, do you?”

“Taverner,” repeated the gentleman in the greatcoat, taking not the smallest notice of Peregrine’s speech. “It has something of a familiar ring, I think.”

“Admiral Taverner,” said Lord Worcester helpfully. “Meet him for ever at Fladong’s.”

“And if that is not enough, sir, to convince you that I am not unworthy of your sword, I must refer you to Lord Worth, whose ward I am!” announced Peregrine.

“Eh?” said Lord Worcester. “Did you say you were Worth’s ward?”

The gentleman in the greatcoat gave Peregrine back his card. “So you are my Lord Worth’s wards!” he said. “Dear me! And—er—are you at all acquainted with your guardian?”

“That, sir, has nothing to do with you! We are on our way to visit his lordship now.”

“Well,” said the gentleman softly, “you must present my compliments to him when you see him. Don’t forget.”

“This is not to the point!” exclaimed Peregrine. “I have challenged you to fight, sir!”

“I don’t think your guardian would advise you to press your challenge,” replied the gentleman with a slight smile.

Judith laid a hand on her brother’s arm, and said coldly: “You have not told us yet by what name we may describe you to Lord Worth.”

His smile lingered. “I think you will find that his lordship will know who I am,” he said, and took Lord Worcester’s arm, and strolled with him into the coffee-room.

Chapter IV

It was with difficulty that Miss Taverner succeeded in preventing her brother from following the stranger and Lord Worcester into the coffee-room and there attempting to force an issue. He was out of reason angry, but upon Judith’s representing to him how such a scene could only end in a public brawl which must involve her, as the cause of it, he allowed himself to be drawn away, still declaring that he would at least know the stranger’s name.

She pushed him up the stairs in front of her, and in the seclusion of her own room gave him an account of her adventure. It was not, after all, so very bad; there had been nothing to alarm her, though much to enrage. She made light of the circumstance of the stranger’s kissing her: he would bestow just such a careless embrace on a pretty chambermaid, she dared say. It was certain that he mistook her station in life.

Peregrine could not be content. She had been insulted, and it must be for him to bring the stranger to book. As she set about the task of arguing him out of this determination, Judith realized that she had rather bring the gentleman to book herself. To have Peregrine settle the business could bring her no satisfaction; it must be for her to punish the stranger’s insolence, and she fancied that she could do so without assistance.

When Peregrine went downstairs again to the coffee-room the strange gentleman had gone. The landlord, still harassed and busy with the company, could not tell Peregrine his name, nor even recall having served Lord Worcester. So many gentlemen had crowded into his inn to-day that he could not be blamed for forgetting half of them. As for a team of blood-chestnuts, he could name half a dozen such teams; they might all have drawn up at the George for anything he knew. Peregrine could only be sorry that Mr. Fitzjohn was already on his way back to London: he might have known the stranger’s name.

By dinner-time Grantham was quiet. A few gentlemen stayed on overnight, but they were not many. Miss Taverner could go to bed in the expectation of a night’s unbroken repose.

She thought herself reasonably safe from any further talk of the fight. It had been described to her in detail at least five times. There could be no more to say.

There was no more to say. Peregrine realized it, and beyond exclaiming once or twice during breakfast next morning that he never hoped to see a better mill, and asking his sister whether he had told her of this or that hit, he did not talk of it. He was out of spirits; after the excitement of the previous day, Sunday in Grantham was insipid beyond bearing. He was cursed flat, was only sorry Judith’s scruples forbade them setting forward for London at once.

There was nothing to do but go to church, and stroll about the town a little with his sister on his arm. Even the gig had had to be returned to its owner.

They attended the service together, and after it walked slowly back to the George. Peregrine was all yawns and abstraction. He could not be brought to admire anything, was not interested in the history even of the Angel Inn, where it was said that Richard the Third had once lain. Judith must know he had never cared a rap for such fusty old stuff. He wished there were some way of passing the time; he could not think what he should do with himself until dinner.

He was grumbling on in this strain when the pressure of Judith’s fingers on his arm compelled his attention. She said in a low voice: “Perry, the gentleman who gave up his rooms to us! I wish you would speak to him: we owe him a little extraordinary civility.”

He brightened at once, and looked round him. He would be glad to shake hands with the fellow; might even, if Judith was agreeable, invite him to dine with them.

The gentleman was approaching them, upon the same side of the road. It was evident that he had recognized them; he looked a little conscious, but did not seem to wish to stop. As he drew nearer he raised his hat and bowed slightly, and would have passed on if Peregrine, dropping his sister’s arm, had not stood in the way.

“I beg pardon,” Peregrine said, “but I think you are the gentleman who was so obliging to us on Friday?”

The other bowed again, and murmured something about it being of no moment.

“But it was of great moment to us, sir,” Judith said. “I am afraid we thanked you rather curtly, and you may have thought us very uncivil.”

He raised his eyes to her face, and said earnestly: “No, indeed not, ma’am. I was happy to be of service; it was nothing to me: I might command a lodging elsewhere. I beg you won’t think of it again.”

He would have passed on, and seeing him so anxious to be gone Miss Taverner made no further effort to detain him. But Peregrine was less perceptive, and still barred the way. “Well, I’m glad to have met you again, sir. Say what you will, I am in your debt. My name is Taverner—Peregrine Taverner. This is my sister, as perhaps you know.”

The gentleman hesitated for an instant. Then he said in rather a low voice: “I did know. That is to say, I heard your name mentioned.”

“Ay, did you so? I daresay you might. But we did not hear yours, sir,” said Peregrine, laughing.

“No, I was unwilling to—I did not wish to thrust myself upon your notice,” said the other. A smile crept into his eyes; he said a little ruefully: “My name is also Taverner.”

“Good God!” cried Peregrine in great astonishment. “You don’t mean—you are not related to us, are you?”

“I am afraid I am,” said Mr. Taverner. “My father is Admiral Taverner.”

“Well, by all that’s famous!” exclaimed Peregrine. “I never knew he had a son!”

Judith had listened with mixed feelings. She was amazed, at once delighted to find that she had so unexpectedly amiable a relative, and sorry that he should be the son of a man her father had mistrusted so wholeheartedly. His modesty, the delicacy with which he had refrained from instantly making himself known to them, his manners, which were extremely engaging, outweighed the rest. She held her hand out to him, saying in a friendly way: “Then we are cousins, and should know each other better.”

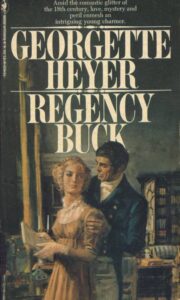

"Regency Buck" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Regency Buck". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Regency Buck" друзьям в соцсетях.