“But why? Why?” demanded Judith, striking the palms of her hands together. “A doubt of Peregrine’s not being old enough could not weigh so heavily with him. I am at a loss to understand him! What did he say then? How did you prevail?”

“I must hope,” said Sir Geoffrey, with a smile, “that the reasonableness of my arguments induced his lordship to relent, but I am more than a little persuaded of his not having heard above half of them. His own reflections seemed to absorb him.”

“Ah, I daresay!” nodded Mrs. Scattergood. “His father was just the same. You might talk to him by the hour together, as I am sure I have done often, and find at the end that he had been thinking of something quite different.”

“As to that, ma’am, I cannot accuse his lordship of letting his mind wander from the subject of my visit. All I meant to say was that his own thoughts operated on his judgment more than my arguments. He took several turns about the room, and upon Captain Audley coming in at that moment briefly informed him of the reason of my being there.”

“Captain Audley! Ah, there you found an ally!”

“Yes, Miss Taverner, it was as you say. Audley immediately advised his brother to consent. With the greatest good nature he declared himself to be in the fullest sympathy with Peregrine’s impatience. He said there could be no object in delay. Lord Worth looked at him as though he would have spoken, but said nothing. Captain Audley, after the shortest of pauses, remarked: ‘As well now as later.’ Lord Worth continued looking at him for a moment, without, however, giving me the impression of attending very closely to him, and suddenly replied: ‘Very well. Let it be as you wish.’”

“So much for prejudice!” said Peregrine. “But I knew how it would be when he came face to face with you, sir. And now you see what a disagreeable fellow we have for a guardian! Ay, you do not like me to say it, Maria, but you know it is so.”

“I confess I had been thinking his lordship very much what you had described to me,” said Sir Geoffrey, “but I am bound to say that from the moment of his giving his consent nothing could have exceeded his amiability. These fashionable men have their whims and oddities, you know. I found him perfectly ready to discuss the details with me; we talked over the settlements, and what income it would be proper for Peregrine to enjoy until he comes of age, and found ourselves in the most complete agreement. He pressed me with the utmost civility to dine with him—an invitation I should have been happy to have accepted had I not felt it incumbent on me to lose no time in coming to set your mind at rest, my dear Perry.”

“Well, and I am sure it has all ended very much to Worth’s credit,” said Mrs. Scattergood. “You and I, my dear sir, can easily understand his scruples, however little these impatient young people may.”

Shortly after this Sir Geoffrey got up to take his leave of them, and until the tea-table was brought in the others were fully occupied in talking over what had passed. A knock on the front door put them in the expectation of receiving another visitor, but in a few minutes the butler came in with a note for Peregrine which had been brought round by hand from the Steyne. It was from Worth, requesting Peregrine to call at his house on the following morning for the purpose of discussing the marriage settlements. Judith listened to it being read aloud, and turned away to pick up one of the volumes of Self-Control from the sofa-table. But not even Laura’s passage down the Amazon had the power to hold her interest. It was evident that Worth had no desire to meet her; he would otherwise have appointed a meeting with Peregrine in Marine Parade.

The interview next morning served to put Peregrine in a mood of the greatest good humour. Worth became once more a very tolerable sort of a fellow, and if his harshness at Cuckfield was not quite forgotten it was in a fair way to being forgiven.

The first person to share the news was Mr. Bernard Taverner, whom Peregrine met in East Street, outside the post office. Peregrine had been feeling a good deal of coldness towards his cousin ever since the affair of his frustrated duel, but his present happiness made him at one with the whole world, and induced him to extend a cordial invitation to Mr. Taverner to drink tea with them in Marine Parade that evening. The invitation was accepted, and shortly after nine o’clock Mr. Taverner’s knock sounded on the door, and he was ushered into the drawing-room, to entertain the ladies with an account of the races, which he had been attending that afternoon, to wish Peregrine joy, and to make himself generally so agreeable that Mrs. Scattergood, feeling all the undoubted attraction of air and manner, could almost find it in her to be sorry that his situation in life made him so ineligible a suitor. He had never been a favourite with her, but she did him the justice to acknowledge that he bore the news of his cousin’s approaching nuptials well—very much better, she guessed, than the Admiral would when next they had the doubtful pleasure of seeing him.

Peregrine’s marriage naturally formed the topic of a great part of their conversation. He was in spirits, and when he had talked over all his own plans, found it easy to quiz his sister, to exclaim at her ill-luck in being obliged to see him married before herself, and to throw out a good many dark hints that she would not be long in following him to the altar. “I do not mention any names,” he said roguishly. “I am all discretion, you know! But it is safe to say that it will not be a certain gentleman who was bred to the sea, nor a tall, thin commoner with his calves gone to grass, nor that cursed rum touch who took you and Maria to the British Gallery, nor—”

“How can you talk so, Perry?” interrupted his sister, turning her head away.

“Oh, I would not betray you for the world!” he replied incorrigibly. “If you have a preference for a red coat that is nothing out of the way! With females a red coat is everything, and if there is one officer amongst your acquaintance who is more dashing and gallant than the rest, I am sure no one can have the least notion who he may be!”

She was put quite out of countenance by this speech, and did not know how to meet her cousin’s grave look. Mrs. Scattergood began to scold, for such talk did not suit her sense of propriety, but her efforts to check Peregrine only provoked him to be more teasing than ever. It was left to Mr. Taverner to give the conversation a more proper direction, which he did by saying suddenly: “By the by, Perry, all this talk of being married puts me in mind of something I had to say to you. You will be enlarging your household, I daresay. Have you room for another groom? I am turning away a very good sort of a man, and should be happy to find him an eligible situation. He leaves me for no fault, but I am putting down my carriage, you know, and unlike you wish to reduce my household.”

“Putting down your carriage!” exclaimed Peregrine, his thoughts instantly diverted. “How comes this about? Do not tell me your pockets are to let!”

“It is not as bad as that,” replied Mr. Taverner, with a slight smile. “But I like to be beforehand with the world when I can, and I believe it will be prudent for me to retrench a little. My father keeps his carriage, of course, so I beg you will not be fancying me forced to walk. But if you have a place for my lad in your stables I should be glad to recommend him to you.”

“Oh, certainly, there must always be something for a second groom to do,” said Peregrine good-naturedly. “Let him come and see me. I will engage for Hinkson’s being obliged to you at least!”

“I can readily believe that he may well be tired of the road to Worthing,” said Mr. Taverner slyly.

If Peregrine could have had his way Hinkson would have seen even more of that road, but happily for him Sir Geoffrey Fairford’s fondness for his son-in-law was not quite enough to make him view with complacence that young gentleman’s presence in his house every day of the week. He bad laid it down as a rule that Peregrine might only visit Harriet on Mondays and Thursdays, but since Lady Fairford’s solicitude would not allow her to permit Peregrine to drive back to Brighton after dark these visits always lasted until the following day, and the lovers were not so very much to be pitied after all.

Mr. Taverner thought it was rather Judith who should be pitied, and said as much to her one evening at the Assembly at the Castle inn. “Perry neglects you sadly,” he remarked. “He thinks of nothing but being at Worthing.”

“I assure you I don’t regard it. It is very natural that he should.”

“You will be lonely when he is married.”

“A little, perhaps. I don’t think of it, however.”

He took her empty glass of lemonade from her, and set it down. “He should count himself fortunate to possess such a sister.” He picked up her shawl, and placed it carefully round her shoulders. “There is something I must say to you, Judith. In your own house Mrs. Scattergood is always beside you; I can never get you alone. Will you walk out with roe into the garden? It is a very mild night; I do not think you can take a chill.”

Her heart sank; she replied in a little confusion: “I had rather—that is, there can be no occasion for that degree of privacy, cousin, surely.”

“Do not refuse me!” he said. “Do you not owe me this much at least, that I should be allowed five minutes alone with you?”

“I owe you a great deal,” she said. “You have been all that is kind, but I beg you to believe that no purpose can be served by—by what you suggest.”

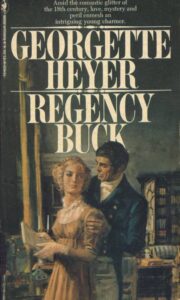

"Regency Buck" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Regency Buck". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Regency Buck" друзьям в соцсетях.