“Certainly not. What you do could never be bad. Let us say rather that it was not very wise.”

She was conscious of a constriction in her throat; she overcame it, and replied: “I am sure I do not care. Such an excessive regard for public opinion is what I have no patience with. Your brother is not here to-night, I think.”

“He was engaged to dine with some friends, but I daresay he will be here presently.”

They went down the dance at this moment, and when they stood opposite to each other again another topic for conversation came up, and continued to occupy them for the rest of the time they were together.

As she walked back beside the Captain to where they had left Mrs. Scattergood, Miss Taverner saw that Worth had entered the room, and was standing talking earnestly to her chaperon. From the glance Mrs. Scattergood cast in her direction she felt sure that she was the subject under discussion, and it was consequently in a very stiff manner that she greeted her guardian.

His bow was formal, his countenance unsmiling; and for the few minutes that he remained beside them he talked the merest commonplace. Tuesday’s events were not referred to, but that they held a prominent place in his thoughts Miss Taverner could not doubt. All the mortifications of her last meeting with him were vividly recalled to her memory by the sight of him, and no softening in his manner, no kinder light in his eyes came to alleviate her discomfort. Upon her civility being claimed towards an officer who approached to lead her out for the next dance, the Earl walked away to the other end of the room, and presently took his place in another set opposite a young lady in a diaphanous gown of yellow sarcenet. He left the ballroom before tea, and without once having asked his ward to stand up with him. She saw him go, and was wretched indeed. As for his taste, she thought very poorly of it, for she could not perceive the least degree of beauty in the lady in yellow sarcenet—nothing, in fact, to have made it worth the Earl’s while to have attended the ball.

The evening provided her with a fair sample of what she guessed she would be obliged to endure until her escapade was forgotten. Several dowagers eyed her with a good deal of severity, and her particular friends seemed to have agreed amongst themselves to behave towards her as though nothing had happened, which they did so carefully that her spirits sank lower than ever. The gentlemen saw the affair as a famous joke; they were ready enough to talk of it, and to applaud her daring; and the boldest amongst them quizzed her with a kind of familiar gallantry which galled her pride beyond bearing.

To make matters worse Mrs. Scattergood bemoaned the results of her imprudence all the way home, and prophesied that the evils of such conduct would be felt for many a long day.

At the end of the week the Regent arrived in Brighton, accompanied by his brother the Duke of Cumberland; and somewhat to Miss Taverner’s surprise a card was received by Mrs. Scattergood inviting them both to an evening party at the Pavilion on the following Tuesday. The royal brothers were seen in church on Sunday: the elder stout, with a sallow sort of handsomeness, and an air of great fashion; the younger lean, extremely tall, and with his black-avised countenance disfigured by a scar from a wound received at Tournai.

Miss Taverner could not forbear looking at him with a good deal of interest, for the scandals attaching to his name were many, and he was generally credited with nearly every form of vice, including murder. Only a couple of years before his valet had committed suicide, and there were still any number of persons who did not scruple to hint that the unfortunate man had not met his end in the way that was officially given out. The Duke of Clarence, who, like every one of his brothers but Cumberland himself, was an invincible and an indiscreet talker, had referred to that particular scandal upon one occasion, and while assuring Miss Taverner that there was no truth in it, had added: “Ernest is not a bad sort, only if he knows where you have a tender spot on your foot he likes to tread on it.” Looking at the Duke of Cumberland’s face, Miss Taverner could well believe this to be true.

Before the party at the Pavilion took place Judith had the comfort of knowing that her cousin was in Brighton. He and her uncle arrived at the Castle inn on Monday at four o’clock, having come down from the White Horse Cellar, in Piccadilly, in a little under six hours, travelling post; and called at Marine Parade after dinner. Peregrine had driven out to Worthing earlier in the day, and was not yet back, but both the ladies were at home, and while Mrs. Scattergood was engaged with the Admiral, Judith was able to take her cousin apart, and pour into his ears an account of her disgrace and its cause.

He listened to her with an expression of concern, and twice pressed her hand with a look of such sympathetic understanding that she was hard put to it not to burst into tears of self-pity. The relief of being able to unburden her heart was great; and the knowledge that there was one at least who did not condemn her induced her to show a more marked degree of preference for her cousin than she was aware of doing.

“You see how bad I have been,” she said with a trembling smile. “But I should never have done it if Lord Worth had not laid it down so positively that I was not to go with Perry.”

“The impropriety of your behaviour is nothing when compared with the total want of delicacy he has shown!” he replied warmly. “You were at fault; your action was ill-judged, but I can readily perceive how you were provoked into doing it. Lord Worth will be content with nothing less than a complete ascendancy over your mind! I have watched with alarm his growing influence over you; it is evident that he thought you would meekly obey his arbitrary commands. Do not be unhappy! He has been betrayed into showing himself to you in his true colours, and that must be of benefit. He is autocratic; the mildness of manner which he has lately assumed towards you is as false as his pretended regard for you. He cares nothing for you, my dear cousin; no man could who could address you in the humiliating terms you have described to me!”

She was considerably taken aback by the vehemence of this speech, nor did its import produce any of that comfort which was presumably its object. The evils of her situation seemed to become greater; she said in a desponding tone: “He has never given me any reason for suspecting him of having a regard for me.”

He looked at her intently. “To me it has seemed otherwise. I have sometimes been afraid that you were even inclined to return his partiality.”

“Certainly not!” she said emphatically. “Such a notion is absurd! I care nothing for his good opinion, and look forward to the day when I shall be free from his guardianship.”

He said with meaning: “And I, too, look forward to that day, Judith.”

Upon the following evening Mrs. Scattergood and Miss Taverner drove in a closed carriage to the Pavilion, and were set down at the domed porch punctually at nine o’clock, and ushered through an octagonal vestibule, which was lit by a Chinese lantern suspended from the centre of the tented roof, into the entrance hall, a square apartment with a ceiling painted to represent an azure sky with fleecy clouds. Here they were able to leave their shawls, and to peep anxiously at their reflections in the mirror over the marble mantelpiece.

Mrs. Scattergood gave their names to one of the flunkeys who stood on either side of the door at the back of the hall; the man announced them, and they passed through the door into the Chinese Gallery.

A numerous company was gathered here, and the Prince Regent was standing in the central division of the gallery in a position to welcome his guests as they came in. His resplendent figure instantly caught the eye, for he had a great inclination towards finery, and his girth, which was considerable, did not prevent him from wearing the most gorgeous waistcoats and coloured coats. His doctors had forbidden him on pain of death to remedy the defects of his figure with tight-lacing, and since he was always very anxious over the state of his own health, he obeyed them. But in spite of his corpulence, and the lines of dissipation that marred his countenance, there were still some traces to be found of the Prince Florizel who had captivated the world thirty-odd years before.

As Mrs. Scattergood, rising from a deep curtsy, begged leave to present Miss Taverner, he smiled, and shook hands with a good-humoured condescension which had often endeared many people to him whom he afterwards contrived without the least difficulty to alienate. With that easy courtesy he knew so well how to assume he insisted that he remembered Mrs. Scattergood well, was happy to see her again (and in such looks), and very glad to make the acquaintance of her young friend. It was difficult to realize that so affable a prince had done what he could to assist in oversetting his father’s precarious reason, had discarded two wives, and heartlessly abandoned any friend of whom he had happened to tire. Miss Taverner knew him to be selfish, capricious, given over to every form of excess, but she could not remember it when he turned to her and said with his attractive smile and air of kindness: “You must know, Miss Taverner, that from one member of my family I have heard so much in your praise that I have been anxious indeed to meet you!”

She hardly knew where to look, but chancing to meet his eyes, which were twinkling archly, she was emboldened to return his smile, and to murmur that he was very kind.

“Is this your first visit to Brighton?” he inquired. “Do you make a long stay? It is a town I have come to regard as so peculiarly my own that it will not be out of place for me to bid you welcome to it.”

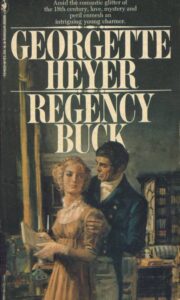

"Regency Buck" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Regency Buck". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Regency Buck" друзьям в соцсетях.