“You would soon wish yourself back in London when the autumn came,” he replied, smiling. “It is very well on a bright summer’s day, but you will find after a while that there is a sameness that makes it all seem insipid.”

“I cannot believe it. Do you find it so?”

“I? No, indeed; did you tell me I had the happiest disposition? But every young lady is soon bored by Brighton, I assure you. It is not at all the thing to continue being pleased with it.”

“I daresay those same young ladies would declare themselves bored in London as easily. For my part, even though the balls and the assemblies palled I could gaze forever on such a prospect as this.”

“I venture to think that the first sober-looking morning will make you change your mind. Or do you refer not to the sea, after all, but to Golden Ball instead? That, I agree, is a prospect one cannot soon tire of.”

She leaned forward to look down into the road, and following the direction of the Captain’s eyes, looked with amused appreciation at a chocolate-coloured barouche, drawn by white horses, which was being driven slowly down the parade by a tall, thin gentleman, who had so exaggerated an air of fashion that he must in any company be remarkable.

“You forget,” she replied, “Mr. Hughes Ball is a sight I have enjoyed in London these six or seven months. He lives in Brook Street, you know, and once did me the honour of calling on me. Who is that queer old gentleman with powdered hair, and a rose in his button-hole? How odd he looks, to be sure!”

“What, do you not know Old Blue Hanger?” demanded the Captain. “My dear Miss Taverner, that is Lord Coleraine. You may know him by his green coat, and his powder. You must have met his brother in town.”

“Oh, Colonel Hanger! Yes, I have met him, of course.”

“And disliked him very thoroughly,” said the Captain, with a twinkle. “He is not such a bad fellow, but to tell you the truth, the Regent’s intimates are never excessively well-liked by the rest of the world. Here is one of them tittuping up the parade now. You must go far before you will find McMahon’s equal. There, the little man in the blue and buff uniform, bowing and scraping before Lady Downshire.”

She remarked: “So that is the Regent’s secretary! He is very ugly.”

“Very ugly, and up to no good.”

Colonel McMahon, having parted from Lady Downshire, was coming slowly along the parade. As though aware of the two pairs of eyes observing his progress, he glanced up as he passed the house, and seeing Miss Taverner, stared very hard at her with an expression of critical approval. She drew back at once, reddening, but the Captain merely said: “Do not be surprised at his quizzing you, Miss Taverner. He has very queer manners.”

Soon after he proposed escorting her for a stroll, to see Rossi’s statue of the Regent, which was placed in front of Royal Crescent;. and upon her agreeing readily to the expedition, it was not long before they had left the house, and were walking up the parade, enjoying on the one side the majestic grandeur of the sea, and on the other the rows of elegant habitations, adorned with columns, pilasters, and entablatures of the Corinthian order, which had been erected during the past dozen years. There was nothing to offend wherever the eye might chance to light: all was in the neatest style, and a series of well-kept squares and crescents saved the parade from too uniform an appearance, and relieved the eye with their welcome patches of verdure.

Mrs. Scattergood met them upon their return to the house, and having exclaimed at seeing her young cousin (whom she had not expected to be in Brighton for some days), extended a cordial invitation to him to accompany them to the play that evening. He accepted with evident pleasure, and after sitting with the ladies for a little while, took his leave of them with a promise of meeting them again later at the theatre.

The theatre, which Mrs. Scattergood and Miss Taverner had passed during the course of their morning’s walk, was situated in the New Road, and though not large, was a handsome building, fitted up with every attention to comfort. The pit and gallery were roomy, and two tiers of lofty boxes, ornamented with gold-fringed draperies, provided ample accommodation for the more genteel part of the audience. The Regent’s box, on the left of the stage, which was separated from the others by a richly gilt iron lattice-work, was empty, but nearly all the others were occupied. Miss Taverner’s time, before the curtain went up, was fully engaged in bowing to those of her acquaintance who were present; Mrs. Scattergood’s in closely observing every cap and turban in the house, and preferring her own to them all.

During the first interval several gentlemen visited their box, among them Colonel McMahon, who came in on the heels of Mr. Lewis, and begged leave to recall himself to Mrs. Scattergood’s memory. She was obliged to introduce him to Miss Taverner, to whom he at once attached himself, remaining by her side throughout the interval, and alternately diverting and disgusting her with the obsequiousness and affectation of his manners. He professed himself to be all amazement at not having met her before, and upon hearing that she had not yet had the honour of being presented to the Prince Regent, assured her that she might depend on receiving a card of invitation to the Pavilion in the very near future.

“I venture to think,” he said impressively, “that you will be pleased alike by the interior of the Pavilion, and by its Royal owner. Such manners are not often met with. You will find His Highness condescending to the highest degree. No one was ever more affable! You will like him excessively, and I am emboldened to say that I can engage for him being particularly pleased with you.”

She could hardly keep her countenance as she thanked him, and was glad that the interval was nearly over. It was time for him to return to his place; he made her a low bow, and went away rubbing his hands together.

During the second interval a circumstance occurred to destroy all Miss Taverner’s pleasure. She became aware of being closely scrutinized, and glancing towards the opposite boxes found that the Earl of Barrymore was fixedly regarding her through his quizzing-glass.

She recognized him at once, and knew from the slight smile on his lips that he had recognized her. He nudged his companion, pointed her out, and very palpably asked a question. Miss Taverner could guess its import, and with a heightened colour turned away.

She took care not to glance in that direction again, but Peregrine, chancing to look round the house, exclaimed suddenly: “Who is that fellow who keeps staring into our box? I have a very good mind to step round and ask him what he means by it!”

“I do not think I should notice his impertinence, if I were you,” replied the Captain. “It is only Cripplegate, and the Barrymores, you know, cannot be held accountable for their odd manners. If you had known Hellgate, the late Earl, you would think nothing of this man.”

Peregrine was frowning across the house. “Yes, but he seems actually to be trying to catch our attention. Ju, you do not know him, do you?”

She looked fleetingly towards the opposite door. The Earl kissed his hand to her, and Captain Audley turned to her with a surprise question in his eyes. “My dear Miss Taverner, are you acquainted with Barrymore?”

She said in a good deal of confusion: “No, no! I have never spoken to him in my life.”

“Well, I think perhaps I will go round and inform him of it,” said the Captain, rising from his chair.

She laid her hand on his sleeve, and said with strong agitation: “It is of no consequence! I am persuaded he mistakes me for another. See, he has found his error for himself, and is no longer looking this way! Pray sit down again, Captain Audley!”

Civility obliged him to comply, though he looked to be far from satisfied. But the third act commenced almost immediately, and as the Earl went away before the farce no further annoyance was suffered that evening.

But the effects of his having recognized in Miss Taverner the curricle-driver at Horley were soon felt. Knowledge of her identity did not prevent him from describing the circumstances under which he had first met her, and by the time she entered the Assembly-rooms at the Old Ship with Mrs. Scattergood on the following evening her name was being bandied about pretty freely, and two ladies who had hitherto treated her with marked amiability bowed with such cold civility that she felt almost ready to sink.

The rooms were full, and a large part of the gathering was composed of officers, with whom, from the circumstance of a Cavalry barracks being situated a little way out of the town on the Lewes road, Brighton always teemed. The Master of Ceremonies presented several of the younger ones to Miss Taverner, but she stood up for the first two dances with Captain Audley.

It might have been her fancy, but she thought that she could detect a shade of reserve in his manner, a grave look in his usually merry eyes. After a little while she said as lightly as she could: “I daresay you have heard by this time of my shocking conduct, Captain Audley. Are you disgusted? Do you think you should stand up with such a sad character as myself?”

“You refer to your drive from town, I collect. I should not have described it in such terms.”

“But you do not approve of it. I can see that you think ill of me for having done it.”

He smiled. “My countenance must be singularly deceptive, then. I think ill of you! No, indeed, I do not!”

“Your brother is very angry with me.”

He returned no answer, and after a moment or two she said with a little laugh: “It was not so very bad, after all.”

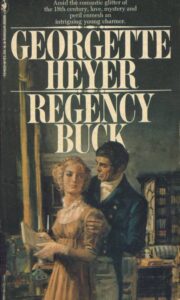

"Regency Buck" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Regency Buck". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Regency Buck" друзьям в соцсетях.