“Well, why don’t you?” said Peregrine.

She had spoken idly, but the notion having entered her head it took root, and she began seriously to consider whether it might not be possible. She very soon convinced herself that there could be no harm in it; it might be thought eccentric, but she who took snuff and drove a perch-phaeton for the purpose of being remarkable, could scarcely regard that as an evil. Within half an hour of having first mentioned the scheme she had decided to put it into execution.

In spite of having assured herself that no objection could be made to it, she was not surprised at encountering opposition from Mrs. Scattergood. That lady threw up her hands, and pronounced the plan to be impossible. She represented to Judith all the impropriety of rattling down to Brighton in an open carriage, and begged her to consider in what a hoydenish light she must appear if she adhered to the scheme. “It will not do!” she said. “It is one thing to drive an elegant phaeton in the Park, and in the country you may do as you please without occasioning remark; but to drive in a curricle down the most crowded turnpike-road in the country, to be quizzed by every vulgar Corinthian who sees you, is not to be thought of. It would look so particular! Upon no account in the world must you do it! That sort of thing can be allowable only in such women as Lady Lade, and I am sure no one could wonder at whatever she took it into her head to do.”

“Do not make yourself uneasy, ma’am,” said Judith, putting up her chin. “I have no apprehension of being thought to rival Lady Lade. You can entertain no scruple in seeing me drive away with my own brother.”

“Pray do not think of it, my love! Every feeling must be offended! But you only wish to tease me, I know. I am persuaded you have too much delicacy of principle to engage on such an adventure. I shudder to think what Worth would say if he were to hear of it!”

“Indeed!” said Judith, taking fire. “I shall not allow him to be a judge of my actions, ma’am. I believe my credit may survive a journey to Brighton in my brother’s curricle. You must know that my determination is fixed. I go with Perry.”

No arguments could move her; entreaties were useless. Mrs. Scattergood abandoned the struggle, and hurried away to send off a note to Worth.

Upon the following day Peregrine came to his sister and said, with a rueful grimace: “Maria must have split on you, Ju. I’ve been at White’s that morning, and met Worth there. The long and short of it is that you are to go in a chaise to Brighton.”

An interval of calm reflection had done much to soften Miss Taverner’s resolve; she could not but admit the justice of her chaperon’s words, and was more than a little inclined to submit gracefully to her wishes. But every tractable impulse, every regard for propriety, was shattered by Peregrine’s speech. She cried out: “What? Is this Lord Worth’s verdict? Do I understand that he takes it upon himself to arrange my mode of travel?”

“Well, yes,” said Peregrine. “That is to say, he has positively forbidden me to take you up in my curricle.”

“And you? What answer did you make?”

“I said I saw no harm in it. But you know Worth: I might as well have spared my breath.”

“You submitted? You let him dictate to you in that insufferable fashion?”

“Well, to tell you the truth, Ju, I did not see that it was such a great matter after all. And, you know, I don’t wish to quarrel with him just now, because I am in hopes that he will consent to my marriage this summer.”

“Consent to your marriage! He has no notion of doing so! He told me as much months ago. He does not mean you to be married if he can prevent it.”

Peregrine stared at her. “Nonsense! What difference can it make to him?”

She did not answer, but sat tapping her foot for a moment, glowering at him. After a pause she said curtly: “You agreed to it, then? You told him you would not drive me to Brighton?”

“Yes, in effect I did, I suppose. I daresay he may be right; he says you are not to be making yourself the talk of the town.”

“I am obliged to him. I have no more to say.”

He grinned at her. “That’s not like you. What have you got in your head now?”

“If I told you, you would run to Worth with the news,” she said.

“Be damned to you. Ju, I would not! If you want to put Worth in his place I wish you luck.”

She looked at him, a glint in her eye. “I will lay you a level hundred, Perry, that I reach Brighton before you on May 12th, driving a curricle-and-four.”

His jaw dropped; then he burst out laughing, and said: “Done! You madcap, do you mean it?”

“Certainly I mean it.”

“Worth goes to Brighton himself on the 12th,” he warned her.

“It would give me infinite pleasure to meet him on the road.”

. “Lord, I would give a monkey to see his face! But do you think you should? Will it not be remarked on?”

“Oh,” she said, curling her lip. “The rich Miss Taverner is expected to astonish the world.”

“Ay, very true; so it is! Well, I am game. It’s time Worth tasted our mettle. We have been too easy with him, and he begins to interfere beyond what is reasonable.”

“No word of it to Maria!” she said. “Not a murmur!” he promised gaily. Mrs. Scattergood, in ignorance of what was in store, and believing herself to have checkmated her charge, set about the business of departure in a mood of considerable complacence. Had she guessed that Miss Taverner’s meek acquiescence in all her plans sprang from nothing but a desire to allay any suspicions she might nourish, her peace would have been quite cut up. But she had never come up against Miss Taverner’s will, and had no idea of its strength. In happy unconcern she went about her affairs, instructed the housekeeper what chairs and sofas must be put into holland-covers, arranged for the servants they were to take with them to leave Brook Street not later than seven o’clock in the morning, and gave orders for the chaise that was to convey herself and Miss Taverner to be brought round at noon. The momentous day dawned. At ten o’clock Miss Taverner, dressed in her habit, and with a handful of spare whip-points thrust through one of her buttonholes, walked into her bedroom where she was fluttering about in the midst of bandboxes and valises, and said coolly: “Well, ma’am, I shall see you presently, I trust. I wish you a pleasant journey.”

Mrs. Scattergood cast one aghast glance at her, and cried: “Good God! what does this mean? Why have you put on your habit? What are you going to do?”

“Why, Ma’am, I have engaged to race Perry to Brighton, driving the other curricle,” said Miss Taverner, preparing to depart.

“Judith!” shrieked Mrs. Scattergood, sitting down plump upon her best bonnet.

Miss Taverner put her head round the door again. “Don’t be uneasy, Maria; I can out-drive Perry. I beg you won’t forget to send word of it to Lord Worth, if he should still be in town.”

“Judith!” moaned the afflicted lady. But Miss Taverner had gone.

In the street Peregrine was tossing his driving-cloak up on to the box of his curricle. Hinkson was to accompany him, while the second curricle was in charge of Judith’s own groom, a very respectable, smart-looking man, with an intimate acquaintance with every turnpike-road in England.

“Well, Ju, is it understood?” asked Peregrine as his sister came out of the house. “We take the New Road, and change three times only, at Croydon, Horley, and Cuckfield. The race to begin the other side of Westminster Bridge, and to end at the Marine Parade. Are you ready?”

She nodded, and taking the reins in her right hand got up on to the box of her curricle, and deftly changed the reins over. Peregrine followed suit, the grooms got to their places, and both vehicles moved forward down the street.

Until Westminster Bridge was crossed the pace was necessarily slow, but once over the bridge, Judith, who had been leading, drew up to let Peregrine come abreast, and the race began.

Very much as she had expected he would Peregrine fanned his horses to a rattling speed immediately, and went ahead. Judith kept her team at a brisk trot, and said merely: “His horses will be blown by the time they reach the top of the first hill. No need to press mine yet.”

A mile and a half brought them to the Kennington turnpike. Peregrine was not in sight, and as the gate was shut it was to be presumed that he must have passed through some minutes previously. The groom had the yard of tin ready, and blew up for the pike in good time; as the curricle drove through he remarked with satisfaction: “The master must be springing ’em. Brixton Hill will take the heart out of his cattle, miss. You may overtake him anywhere you please between Streatham and Croydon.”

Another two and a half miles brought Brixton Church into sight. There was no sign of Peregrine, but instead an Accommodation coach, loaded high with baggage, presented a ludicrous appearance with a wheel off, and all its disgruntled passengers sitting or standing by the roadside. No one seemed to be hurt, and Judith, checking only for a minute, drove past, and into Brixton village. She had been nursing her horses carefully, and they brought her up the hill beyond at a good pace. She steadied them over the crown, swept past a stage-coach painted bright green and gold, with its destination printed in staring white capitals on the panels, and let her horses have their heads. Peregrine’s curricle came into sight a mile farther on, crossing Streatham Common. His horses were labouring and it was evident that he had pressed them too hard up Brixton Hill. Judith gained on him steadily; he sent the lash of his whip out to touch up one sluggish leader, and the wheeler behind shied badly. Judith seized her chance, demonstrated how to hit a leader without alarming the wheel-horse by throwing her thong out well to the right, and bringing it back with a sharp jerk, and shot by at a gallop just as the Royal Mail Coach came into sight round a bend. The curricle swung over to the side of the road, and the two vehicles met and passed without mishap.

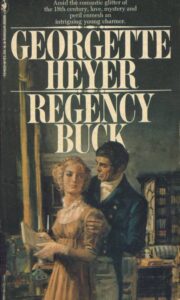

"Regency Buck" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Regency Buck". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Regency Buck" друзьям в соцсетях.