“Mine’s just over,” replied Peregrine. “Three years old, and the sharpest heel you ever saw. My cocker has had him preparing these six weeks. He’s resting him now.” He bethought him of something. “By the by, Fitz, if you should chance to meet my sister you need not mention it to her. She don’t above half like cocking, and I haven’t told her I’ve had my bird brought down from Yorkshire.”

“Lord, I don’t talk about cocking to females, Perry!” said Mr. Fitzjohn scornfully. “I’ll be there on Tuesday. What’s the main?”

“Sixteen.”

“Bad number. Don’t like an even set,” said Mr. Fitzjohn, shaking his head. “Half-past five, I suppose? I’ll meet you there.”

He was not a young gentleman who made a habit of punctuality, but his watch being, unknown to himself, twenty minutes ahead of the correct time, he arrived at the Cock-Pit Royal, in Birdcage Walk, on Tuesday evening just as the cocks were being weighed and matched. He joined Peregrine, and saw the grey taken out of his bag, and looked him over very knowingly. He admitted that he was of strong shape; closely inspected his girth; approved the beam of his leg; and wanted to know whose cock he was matched with.

“Farnaby’s brass-back. It was Farnaby who suggested I might enter my bird, but he’ll make that brass-back look like a dunghill cock, eh, Flood?”

The cocker put the grey back into his bag, and looked dubious. “I don’t know as I’d say just that, sir,” he answered. “He’s in good trim, never better, but we’ll see.”

“Don’t think much of your bag,” remarked Mr. Fitzjohn, who liked bright colours.

The cocker gave a slow smile. “‘There’ll come a good cock out of a ragged bag,’ sir,” he quoted. “But we’ll see.”

The two young men nodded wisely at the saw, and moved away to take up their places on the first tier of benches. Here they were joined by Mr. Farnaby, who squeezed his way to them, and after a slight altercation prevailed on a middle-aged gentleman in a drab coat to make room for him to sit down beside Peregrine. Behind them the benches were being rapidly filled, and higher still the outer ring of standing room was tightly packed with the rougher members of the crowd. In the centre of the pit was the stage, on which no one but the setters-on was allowed. This was built up a few feet from the ground, covered with a carpet with a mark in the middle, and lit by a huge chandelier hanging immediately above it.

The first fight, which was between two red cocks, only lasted for nine minutes; the second was between a black-grey and a red pyle, and there was some hard hitting in the pit, and a great deal of noisy betting amongst the spectators. During this and the next fight, which was between a duck-winged grey and a red pyle, Peregrine and Mr. Fitzjohn grew much excited, Mr. Fitzjohn betting heavily on the red’s chances, extolling his tactics, and condemning the grey for ogling his opponent too long. Peregrine in honour bound backed the grey to win, and informed Mr. Fitzjohn that crowing was not fighting, and nor was breaking away.

“Breaking away! You’ve never seen a red pyle break away!” said Mr. Fitzjohn indignantly. “There! Look at him! He’s fast in the grey; they’ll have to draw his spurs out.”

The fight lasted for fifteen minutes, both birds being badly mauled; but in the end the red sent the grey to grass, dead, and Mr. Fitzjohn shook a complete stranger warmly by the hand, and said that there was nothing to beat a red pyle.

“Good birds, I don’t deny, but I’ll back my brass-back against any that was ever hatched,” said Mr. Farnaby, overhearing. “You’ll see him floor Taverner’s grey, or my name’s not Ned Farnaby.”

“Well, you’d better be thinking of a new one then, for our fight’s coming on now,” retorted Peregrine.

“Pooh, your bird don’t stand a chance!” scoffed Farnaby.

The setters-on had the cocks in the arena by this time, and Mr. Fitzjohn, critically looking them over, declared there to be very little to choose between them. They were well matched; their heads a full scarlet; tails, manes, and wings nicely clipped; and spurs very long and sharp, hooking well inwards. “If anything I like Taverner’s bird the better of the two,” pronounced Mr. Fitzjohn. “He looks devilish upright, and I fancy he’s the largest in girth. But there ain’t much in it.”

The birds did not ogle each other for long; they closed almost at once, and there was some slashing work which made the feathers fly. The brass-back was floored, but came up again, and toed the scratch. Both birds knew how to hold, and their tactics were cunning enough to rouse the enthusiasm of the crowd. The betting was slightly in favour of the grey, which very much delighted Peregrine, and made Mr. Fitzjohn shake his head, and say that saving only his own red pyle he did not know when he had seen a cock he liked better. Mr. Farnaby did not say anything but looked at Peregrine sideways once or twice and thrust out his under-lip.

The cocks had been fighting for about ten minutes when the brass-back, who had till now adopted more defensive tactics than the grey, suddenly rushed in, striking and slashing in famous style. The grey responded gallantly, and Mr. Fitzjohn cried out: “The best matched pair I ever saw! There they go, slap for slap! I’ll lay you any odds the grey wins! No, by God, he’s down! Ha, spurs fast again!”

The setters-on having secured their birds, and the brass-back’s spurs being released, both were again freed. The grey seemed to be a little dazed, the brass-back hardly less so. Both were bleeding from wounds, and neither seemed anxious to close again with his opponent. They stayed warily apart, ogling each other while the timekeeper kept the count, and fifty being reached before either showed any disposition to continue fighting, setting was allowed. The setters-on each took up his bird and brought him to the centre of the arena, and placed him beak to beak with the other. The grey was the first to strike, a swift, punishing blow that knocked the brass-back clean away.

A sudden commotion arose amongst the spectators. Mr. Farnaby sprang up, shouting “A foul! A foul! The grey was squeezed!”

Someone called out: “Nonsense! No such thing! Sit down!”

Peregrine swung around to stare at Farnaby. “He was not squeezed! I was watching the whole time, and I’m ready to swear my man did no more than set him!”

The setters-on, pending the referee’s decision, had each caught his bird, a lucky circumstance for the brass-back, who seemed to have been badly cut up by the last blow. The referee gave it in favour of the grey, and Mr. Fitzjohn said testily: “Of course the grey was not squeezed! Sit down, man, sit down! Hey, no wonder your cock’s shy! I believe the grey got his eye in that last brush. Perry, that’s a rare bird of yours! We’ll match him with mine one day, down at my place. Ha, that finishes it! The brass-back’s a blinker now—or dead. Dead, I think. Well done, Perry! Well done!”

Mr. Farnaby turned with an ugly look on his face. “Ay, well done indeed! Your cock was craven, and was squeezed to make him fight.”

“Here, I say, Farnaby, learn to take your losses!” said Mr. Fitzjohn with strong disapproval.

Peregrine, a gathering frown on his boyish countenance, lifted a hand to hush his friend, and fixed his eyes on Farnaby’s. “You can’t know what you’re saying. If there was a fault the referee must have seen it.”

“Oh,” said Farnaby, with a sneer, “when rich men fight their cocks referees can sometimes make mistakes.”

It was not said loud enough to carry very far, but it brought Peregrine to his feet in a bound. “What!” he cried furiously. “Say that again if you dare!”

Though no one but those immediately beside Farnaby could have heard his words, it was quite apparent to everyone by this time that an altercation was going on, and the rougher part of the gathering at once began to take sides, some (who had lost their money on the brass-back) loudly asserting that the grey had been squeezed, and others declaring with equal fervour that it had been a fair fight. Above the hubbub a shrill Cockney voice besought Peregrine to darken Mr. Farnaby’s daylights—advice of which he did not seem to stand in much need, for he was clenching his fists very menacingly already.

Mr. Fitzjohn, who had also heard Farnaby’s last speech, tried to get between him and Peregrine, saying in a brisk voice: “That’s enough of this foolery. You’re foxed, Farnaby. Ought to be ashamed of yourself.”

“Oh, I’m foxed, am I?” said Farnaby, keeping his eyes on Peregrine’s. “I’m not so foxed but what I can see when a bird’s pressed to make him fight, and I repeat, Sir Peregrine Taverner, that money can do queer things if you have enough of it.”

“Oh, damn!” said Mr. Fitzjohn, exasperated. “Pay no heed to him, Perry.”

Peregrine, however, had not waited for this advice. As Mr. Fitzjohn spoke he drove his left in a smashing blow to Farnaby’s face, and sent that gentleman sprawling over the bench. There were a great many cheers, a shout of “A mill, a mill!” some protests from the quieter members of the audience; and the man in the drab coat, across whose knees Mr. Farnaby had fallen, demanded that the Watch should be summoned.

Mr. Farnaby picked himself up, and showed the house a bleeding nose. The same voice which had counselled Peregrine to strike shouted gleefully: “Drawn his cork! Fib him, guv’nor! Let him have a bit of home-brewed!”

Mr. Farnaby held his handkerchief to his nose and said: “My friend will call on yours in the morning, sir! Be good enough to name your man!”

“Fitz?” said Peregrine curtly, over his shoulder.

“At your service,” replied Mr. Fitzjohn.

“Mr. Fitzjohn will act for me, sir,” said Peregrine, pale but perfectly determined.

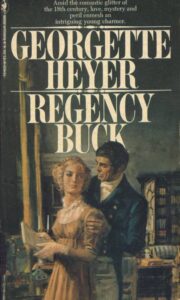

"Regency Buck" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Regency Buck". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Regency Buck" друзьям в соцсетях.